Artificial Intelligence: Thinking Outside the Box

Will machines soon be smarter than humans? An AI expert talks about where the technology stands, where it’s headed, and what we should be concerned about.

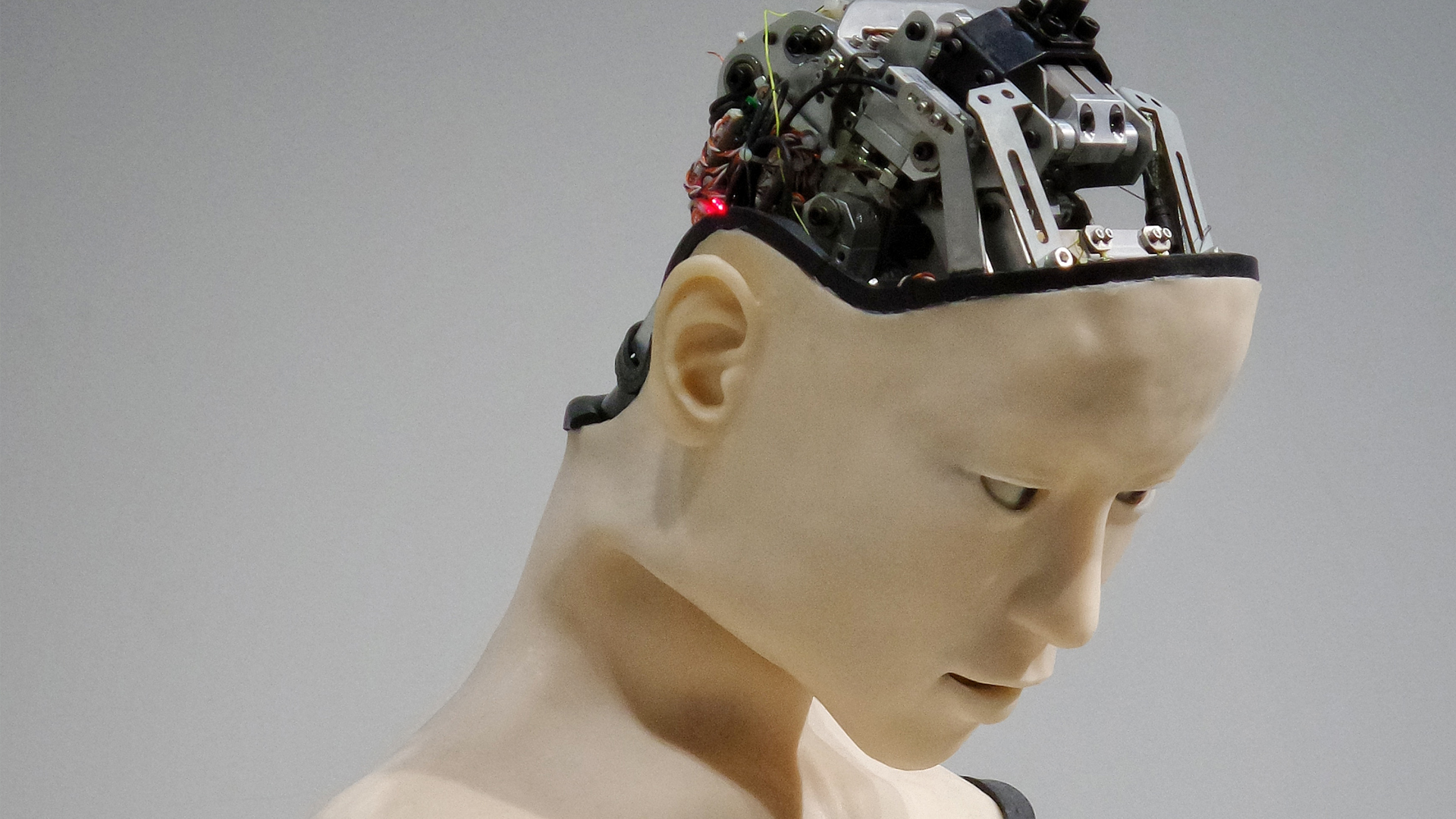

Artificial intelligence (AI) is no longer the stuff of science fiction. While robot maids may not yet be a reality, researchers are working hard to create reasoning, problem-solving machines whose “brains” might rival our own. Should we be concerned?

Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh (anglicized as Sean O’Hegarty), while enthusiastic about the benefits that AI can bring, is also wary of the technology’s dark side. He holds a doctorate in genomics from Trinity College Dublin and is now executive director of the Center for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge. He has played a central role in international research on the long-term impacts and risks of AI.

Vision publisher David Hulme spoke with him about not only the current state of the technology but also where it’s heading.

Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh, executive director of the Center for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge

DH What would a short summary of the history of AI look like?

SOH Artificial intelligence as an idea could be thought of as having been born in the 1950s. Some of these ideas were floating around earlier, but one of the really pivotal moments was a conference held in Dartmouth in 1956, where some of the most brilliant thinkers in computer science and other fields got together and set themselves the task of creating machines that were able to think and reason like humans. They were very optimistic and ambitious. They thought many of the challenges that have taken us the 60 years since then would be done over the course of a couple of years, and that things like machine vision and machine translation would be hard but achievable with a small team over the course of a few months.

I would see that as the formal beginning of the field of artificial intelligence.

DH Are we making progress as we thought we would at the time?

SOH I think we’re not, but we are making progress. As in many scientific fields, creating artificial intelligence turned out to be much more difficult than it originally looked.

In hindsight this is probably not surprising. Intelligence is one of the most complex things that exists. The thought that we could recreate this or something equivalent within the course of a few months or years was perhaps a bit optimistic. Over the last 60 years or so, there have been bursts of progress followed by apparent slowing down, described as AI summers and winters. Often a particular approach has borne initial fruit only to get no further.

Over the course of the last decade a lot of progress has been driven by an approach known as machine learning. The thing that makes it unique is that machine-learning systems aren’t hard-programmed to follow through a specific set of steps. Instead, they’re able to analyze data and either take an action or come to an answer without being specifically programmed for that task.

DH You’ve been involved with both the concept of existential risk and the development of AI. According to one of your colleagues, Nick Bostrom, “the transition to the machine-intelligence era looks like a momentous event and one I think associated with significant existential risk.” If that’s true, what is the risk, and is it existential?

SOH It’s important to note that when Nick Bostrom talks about the transition to machine intelligence and existential risk, he’s not speaking about the artificial intelligence systems that we have in the world today. He’s looking forward to the advent of what we might term “artificial general intelligence,” the kind of general reasoning, problem-solving intelligence that allows us to dominate our environment in the way that the human species has. We’re currently nowhere near that, and experts are divided on how long it will take us to achieve it. But it’s very unlikely to be less than a decade, and it could be many decades according to some. However, were we to achieve this, it would undoubtedly change the world in more ways than we can imagine.

“If we were to create intelligence that was equivalent to or perhaps even greater than ours, it would be imprudent to assume that that would go very well for us.”

We have harmed our own environment more than any other species. We’re wiping out species at a huge rate; we’re changing our climate in a way that might be unsustainable for our future. If we’re to bring into this world intelligence—either as our tools or as independent entities—that’ll allow us to change the world even more, we need to think very carefully about the kinds of goals we give them and the level of autonomy these future systems might have, because it may be very difficult for us to turn back the clock.

This is not the AI that we have in the world today or tomorrow or next year. But I do think it’s very worthwhile for people to be thinking in advance about whether we are on that trajectory and the steps we want to take.

DH In the February 2018 report “The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation,” you say: “Artificial intelligence is a game changer. In this report is imagined what the world could look like in the next five to ten years.” You note further: “Our report is a call to action, for government institutions and individuals across the globe.” So what’s been the reaction from governments, corporations, individuals?

SOH The reaction has actually been very positive. We initially worried that people would say it’s scaremongering. That was very much not our intention. The idea was that all of the authors, many of whom are involved in artificial intelligence development themselves, were motivated to identify and mitigate potential negative uses in order to achieve the positive uses that we’re all excited about. We were very pleased to see that the report was taken up in this vein. We got very positive comments and are in the process of organizing some follow-on workshops. The authors of the report have all received a number of invitations to speak on the findings of the report. (I’ve just returned from a meeting with UN experts, organized by the United Nations University.)

One of the main recommendations that we were trying to bring across is that with artificial intelligence developing quite quickly and being applied to so many different safety-critical systems in our world, we need to start closer work between machine-learning experts, who really understand the state-of-the-art of the technology; policymakers and lawyers, who need to legislate around it and guide governmental strategy; and civil infrastructure people and social scientists, who need to think about the impact. We were particularly interested in the ways in which people might misuse or adapt benign advances in artificial intelligence to cause harm in various ways, and how to stop that.

DH What are the main applications of AI that we need to be concerned about?

SOH We looked at three domains in particular: digital (by which we mean, for example, cyber attack and cyber defense), physical (ways in which physical infrastructure could be attacked), and political (advances in surveillance, automated propaganda—targeting anything that might allow malicious actors to subvert political processes or to interfere with truthful discussion and debate).

We identified three broad trends that cut across these areas. One was that intelligence will allow expansion of the threats we currently face. Another is that it’ll introduce new types of threats that will require new approaches to mitigate. And a third is that it will change the character of the threats we face in a number of ways.

To give an example of an expansion of threats: In a cyber attack, right now there’s a huge difference between the effectiveness of what is known as spear phishing versus phishing. Phishing is when somebody sends out a malicious e-mail to try to get you to click on a bad link or something. If you get an e-mail from a Nigerian prince offering you $50 million, you probably say “Nah” and just put it aside. A spear-phishing attack, by contrast, usually involves a human or a group of humans who will take a lot of time to identify you as a high-value target, to learn everything they can about you so they can tailor a specific attack to you that will look convincing.

“It looks like it comes from somebody you trust or includes enough personal information that you don’t see it as a malicious attack. Those are much more effective; even cyber and security experts will fall for them.”

Right now there’s a limit to how many of these kinds of effective attacks take place, because it requires a lot of human expertise and time. But if someone is able to automate quite a bit of the process, then suddenly it becomes available to a lot more actors, and a lot cheaper. For example, an automatic system scans and identifies you as a high-value target, because of either the organization you’re part of or your wealth or patterns of activity. The system could then gather an awful lot of information about you—your social media profile, your activities. Then, by automating various bits of the process, it allows you to be fooled by the attack—whether by helping to craft a message that you’re more likely to click on, inclusion of bits of information that make it feel like this e-mail is relevant to you, or even synthesized voice or images. We’re getting to the point where somebody could turn a message that they recorded in their own voice into something that sounds like the voice of somebody you know (if they have enough samples of that person’s voice). And so suddenly you have the tool box to allow a more sophisticated attack that might be available to many more people than in the past.

Right now only a very well resourced group could do something like develop Stuxnet or take down the Ukraine power grid. But again, if many aspects of what makes that a high-expertise, high-time, high-resource attack can be automated, then perhaps we might see more of these kinds of attacks.

Artificial intelligence systems themselves can be attacked in ways that are different from traditional computer systems. One example is the idea of an adversarial attack, where if you feed the right kind of image or the right kind of pixels into a system, you can fool that system into thinking it’s seeing something it’s not seeing. It’s been shown, for example, that if you change just a couple of pixels on a stop sign that a self-driving vehicle sees, it reads it as a go sign; you can imagine doing something like this at scale and causing quite a few crashes. Now, I think there’ll be enough eyes on self-driving cars that this won’t happen in that context. But if we’re going to be introducing these systems into everything from health care to transport to civilian infrastructure, we need to think about the new ways in which these systems might be attacked.

Another example might be in the physical domain. Right now there is no way in which a human could operate a drone swarm, such as a swarm of small flying robots. But artificial intelligence would allow coordination and communication between these drones and, potentially, allow a very powerful attack. That’s an entirely new weapon that might become available to people in the next five to ten years.

DH Martin Rees addresses the danger of existential risks caused by rogue actors when he says, famously, “The global village will have its village idiots.” Are these the only individuals you’re trying to impede?

SOH I certainly think we need to be worried about the lone actors and the village idiots. One of the concerning factors is that advances in both artificial intelligence and biotechnologies (and Martin has written about this a lot) might allow the lone wolf to do more sophisticated and more high-consequence harms than they would have been able to do in the past. However, I think it would probably be naive to rule out more powerful non-state actors and even state actors. We’ve seen over the last year that certain states have attempted to interfere in the political processes of other states. We’re not past the stage of seeing large-scale conflicts and wars, and I think we need to be worried about that. And in a world where we face the pressures of climate change, large-scale migration, food/water security, the food-water-energy nexus, I think we need to be worried about what well-resourced groups might do, as well as the lone wolves.

DH What does the Russian election propaganda–social media situation tell us about the human element in the misuse of AI? Personal data can be used for good purposes (marketing) or bad purposes (manipulation).

SOH I think the Russian manipulation shows that there are a lot more ways in which we can be influenced than we necessarily realized, and it can happen at a greater scale. It’s a harbinger of what might be if we don’t think carefully about these things. So, for example, I’ve read that Russian hackers sent something like 10,000 tailored tweets to members of the Department of Defense (in the US) and others. Right now I imagine that meant a lot of people writing these tweets; but again, if we can automate some of these processes, then we might see even larger-scale attempts to interfere, or those tools becoming available to more people. We need to think carefully about how technologies will be used, because certainly the people who are developing the techniques that underlie this kind of automation are not doing it in order to enable hacking of elections. They’re doing it for all sorts of benign purposes to reduce the drudgery of lots of things that we waste time on.

“What it really shows is the dual-use potential of many technologies—that we can develop them with only beneficial purposes in mind, but we need to be mindful that people will find a way of repurposing them, which won’t necessarily be benign.”

DH: What should the person in the street be worried about when it comes to AI?

SOH I think the person in the street should be thinking about what job they do, what are the skills involved in that job, and whether it’s likely that those skills can be automated on a 10- or 20-year horizon. Moreover they should be thinking about what kind of education their children are getting, and whether that education enables flexible, creative problem-solving abilities that will be crucial in a world in which new jobs are opening up but where a lot of the traditional sectors of employment are going away.

The person in the street should be very mindful of their online security, because the kinds of attacks they might encounter will go from the crude and easily spotted to the more sophisticated and easy to fall for.

The person in the street should also be mindful of the ways in which technology is enabling far more gathering of information about them, potentially influencing their actions, whether by commercial actors or by the state. As a result, the person in the street should make sure to exercise his or her democratic rights and make sure that the rules and policies that are being enacted around these technologies are consistent with their values.

DH What does it mean to have one’s identity stolen in this modern AI world?

SOH That’s a good question. We’ve been familiar in the past with the idea of credit card fraud and bank fraud. In a world in which we can create a voice file of you appearing to say something that I scripted, I think we could see a much more sophisticated level of stolen identity. And given that we’re seeing this environment of fake news, and people refuting things that they actually did say, it’s going to get harder and harder to know what is real and what is fake.

DH So what keeps machines from actually taking over if something went haywire—maybe an AI decision to shut down the grid to preserve its own integrity? Will humans still have power to override a bad computer decision?

SOH For the time being, yes, and by “for the time being” I mean for the coming years and probably decades. In the near term a more pressing concern is that it may not be apparent to us that a machine is on a bad track until it’s too late to intervene without harm.

An early version of this might be the [2010] stock market crash, where you had misbehavior of algorithms (among other things) that cascaded, but everything was going so quickly that by the time humans were able to intervene, a significant value was wiped off the stock market.

We do need to be very careful as we introduce AI systems into more and more critical infrastructure, and it’s essential that we at all times try to understand how these systems are coming to the decisions they are. What are the circumstances in which they will work well? What the circumstances in which they’ll fail?

We are not yet anywhere near the level of technology that would allow AI systems to display a lot of creative problem-solving in pursuit of their goals, including taking actions to avoid being shut down other than in very simple game settings. So this is a concern for the long-term-research community, but it’s not one that I think needs to keep the average person awake at the moment.