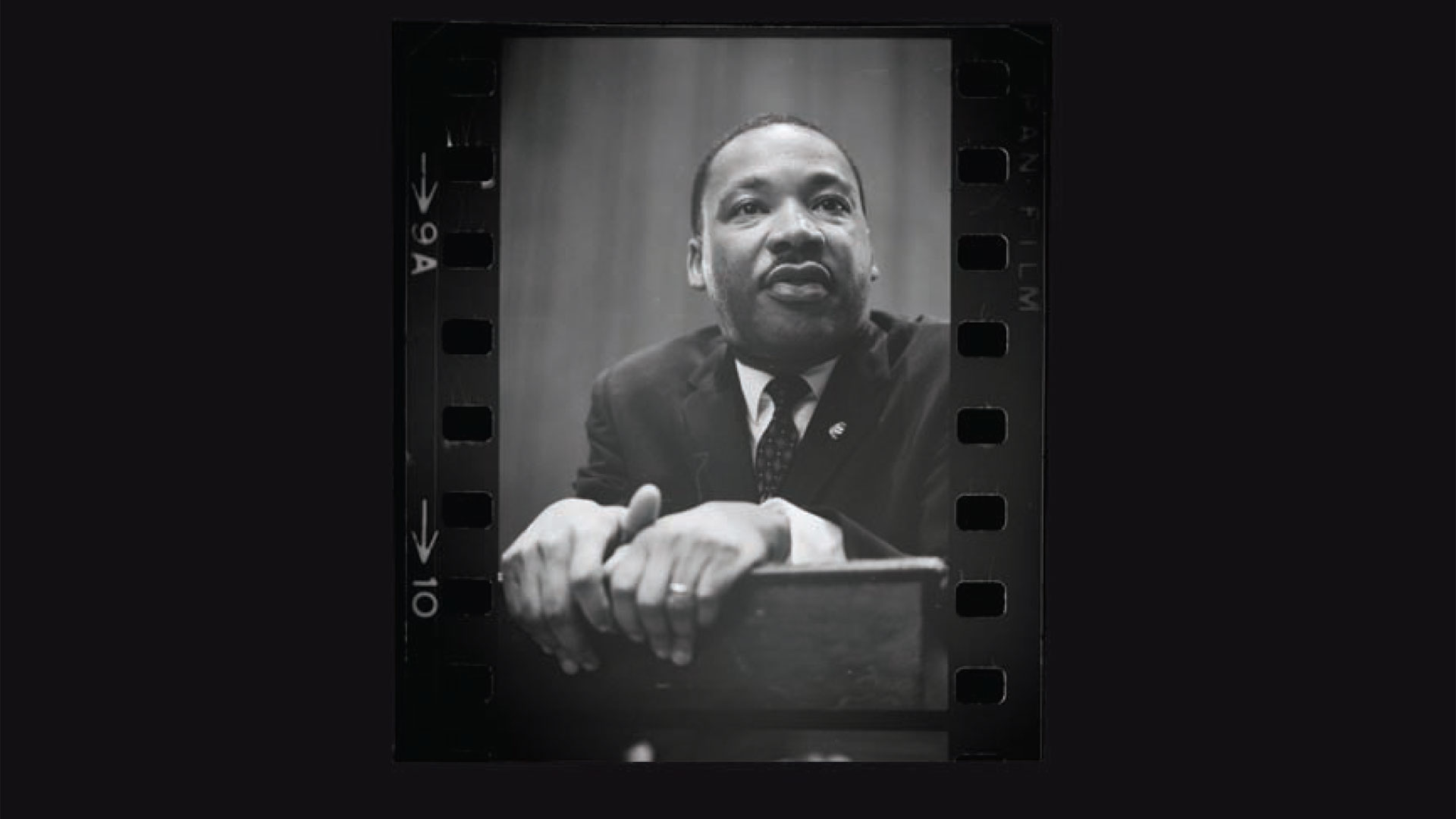

Martin Luther King Jr.: A Man With a Dream

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

As a 14-year-old boy, Martin Luther King Jr. showed a remarkable ability for persuasive speech. Representing his school at a statewide oratory contest in 1944, King traveled by bus from his home in Atlanta to Dublin, Georgia. He won the contest with a speech titled “The Negro and the Constitution.”

“We cannot have a nation orderly and sound with one group so ground down . . . ,” he asserted. “We cannot be truly Christian people so long as we flout the central teachings of Jesus: brotherly love and the Golden Rule. . . . So as we gird ourselves to defend democracy from foreign attack, let us see to it that increasingly at home we give fair play and free opportunity for all people.”

That evening, King was required to give his seat to a white traveler and stand in the aisle while the bus traveled the 90 miles back to Atlanta.

Martin Luther King Jr. was born in Atlanta in 1929 and raised in an entrenched system of racial segregation. He could not swim in the public pools, enjoy the parks, eat at most department store lunch counters or enter a movie theater. But his life was more than public inconveniences. It was the life of an underclass victimized by racial prejudice and hatred.

In 1931 his father, Martin Luther King Sr., became the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, one of the leading black congregations in Atlanta. The elder King was a dynamic individual possessed of strength, character and an unwavering conviction regarding the right treatment of all people. From the family’s fundamental faith, the pastor’s young namesake learned that the cycle of racial hatred could be broken only by an attitude and application of Christian love and concern for others. He learned that concern for the well-being of others must be extended even to the oppressor. Christ’s admonition to pray for those who look on you with contempt and persecute you was more than just a verse of Scripture in the King home. This foundational belief would later find expression as King embraced nonviolent direct action as a tactic of the American civil rights movement.

When he was 15, King entered Morehouse College, where both his father and his maternal grandfather had attended. The college’s intellectual atmosphere created both skepticism and stimulation: skepticism in that he could not see how the fundamentalism and emotionalism of the black church could be used as an agent for modern thinking and social change; stimulation as he experienced a discussion of racial issues openly and absent the component of fear. It was also there that he was introduced to the concept of nonviolence through Thoreau’s essay “On Civil Disobedience.” After graduating from Morehouse in 1948, King’s education continued at Crozer Theological Seminary and at Boston University School of Theology, where he earned his doctorate.

King’s education expanded the Bible message he had heard from childhood into a contemporary discussion regarding the problems of race. He studied Walter Rauschenbusch’s Christianity and the Social Crisis and Reinhold Niebuhr’s Moral Man and Immoral Society, as well as the works of classic and contemporary philosophers and theologians. King began to view the gospel message as more than fire insurance for the future.

His desire to serve humanity and bridge the gap between preaching deliverance in the pulpit and bringing deliverance to the community led him to seek a vehicle for social reform. A lecture on Gandhi and nonviolent action offered a vision of the power inherent in the doctrine of love. Christ’s message of turning the other cheek could be expanded beyond personal relationships and used as a tactic for broad-based social change.

“The ultimate test of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and moments of convenience, but where he stands in moments of challenge and moments of controversy.”

King entered the ministry in 1948, at the age of 19, and at 25, a year after marrying Coretta Scott, he became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. The confluence of time, circumstance, and a community poised to protest Montgomery’s segregated bus policies launched him onto the national stage as leader of the boycott campaign.

Success in Montgomery taught civil rights advocates that mass protest and organized direct-action campaigns could be useful tools in focusing attention on the plight of African Americans across the South. It also taught that such campaigns were useful agents in encouraging the federal government to create change, and that change could be achieved without protestors resorting to violence, even in the face of provocation.

However, there was no South-wide organization to act as an agent for change. To address this vacuum, King called for a meeting of leading African American ministers from across the South in January 1957. As a result, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was formed, with King as its president. He would maintain this position throughout his lifetime.

King was not the leader of the civil rights movement, nor was the SCLC the lead organization in the movement. In time, other leaders and organizations would begin to criticize King for appearing to take some credit for initiatives that neither he nor the SCLC began. But because of his great gift of language and his moderate approach, the media frequently sought him out as the interview source for major happenings. It is a severe misreading of history to try to encapsulate the movement through primarily one individual. But King did mobilize when others could not, and he did lend a voice that resonated with a wide variety of listeners, introducing them to the reality of a national injustice.

There were many defining moments in the civil rights movement. Before passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, King had achieved great visibility in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the Birmingham Campaign and the March on Washington. But beyond these events, he spoke widely and frequently from pulpit and public platform across the country to break the chains of segregation practices in the South. He met with governors and presidents and international leaders.

As the struggles of an oppressed people came increasingly to light, King articulated the emotions and faith of the black church in his appeal for right treatment of fellow man, an appeal that reverberated across disparate American cultures. His fight against segregation was more about creating friendship and brotherhood among peoples than defeating an enemy. Defeating injustice, yes; but it was the act of injustice, not the perpetrator.

Hatred only served to create more hatred and violence more violence, said King. The country had exceeded its ration of both, and he now proclaimed what he saw as a better way forward using the direct-action but nonviolent methods of boycotts, marches, sit-ins and freedom rides to bring focus and pressure for change.

The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was an iconic moment in American history, yet the act did little to ensure voting rights for southern blacks. New barriers to black voter registration were soon established across southern counties; without the vote, victory was hollow.

Allied civil rights organizations began new campaigns in the South to ensure the vote. It would be one of the last acts of unity among these organizations, and in the end it would serve to create further dissonance between King and other movement leaders.

Events came to a volatile head during the 1964 “Freedom Summer” in Mississippi and the following spring in Selma, Alabama, where beatings, killings and a brutal police response to a peaceful march sparked tensions. When King bowed to pressure from Washington to abide by a federal injunction prohibiting further marches, many in the movement felt betrayed.

The widening divide between SCLC and one other group in particular, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), could no longer be bridged. King’s appeal for moderate action in Selma was viewed as weakness. The nonviolent period, so passionately trumpeted by King, was coming to an end. In a short time SNCC’s Stokely Carmichael would use the term Black Power to signal the beginning of a more militant period.

After the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965, King began to focus on a wider range of social issues. He moved his family to the slums of Chicago to bring attention to the issues of housing discrimination and the living conditions of the poor. He brought an expanded agenda to the SCLC, arguing that Jim Crow practices were only part of the evils of racism. Poverty and lack of opportunity were related evils, and he therefore called for a redistribution of political and economic power across the country. He also began to take a strong anti–Vietnam War stance, labeling it a distraction from the greater problems at home. King’s position on Vietnam cost him access to and the support of his ally, President Lyndon B. Johnson.

By 1966 King’s appeal was fading. As the movement expanded into major cities across the country, the nonviolent approach gradually lost traction. Youthful African-Americans began to identify with the militant approach of Carmichael, Malcolm X and others, who increasingly articulated the emotions of many urban blacks.

King was killed by an assassin’s bullet on April 4, 1968, a victim of the racial hatred he sought so desperately to overcome. He was only 39. The country mourned the death of the man who had been a moving force in cleansing a 350-year-old national stain from the fabric of the country.

Martin Luther King Jr. built his life on a foundation of family and faith, and at his death he left a legacy from which we all benefit. Central to that legacy was his constant belief that anger, bitterness, hatred and violence cannot solve humanity’s problems: “Hatred makes nothin’ but more hatred,” his grandmother had once told his father. “Don’t you do it.”