Purging the People

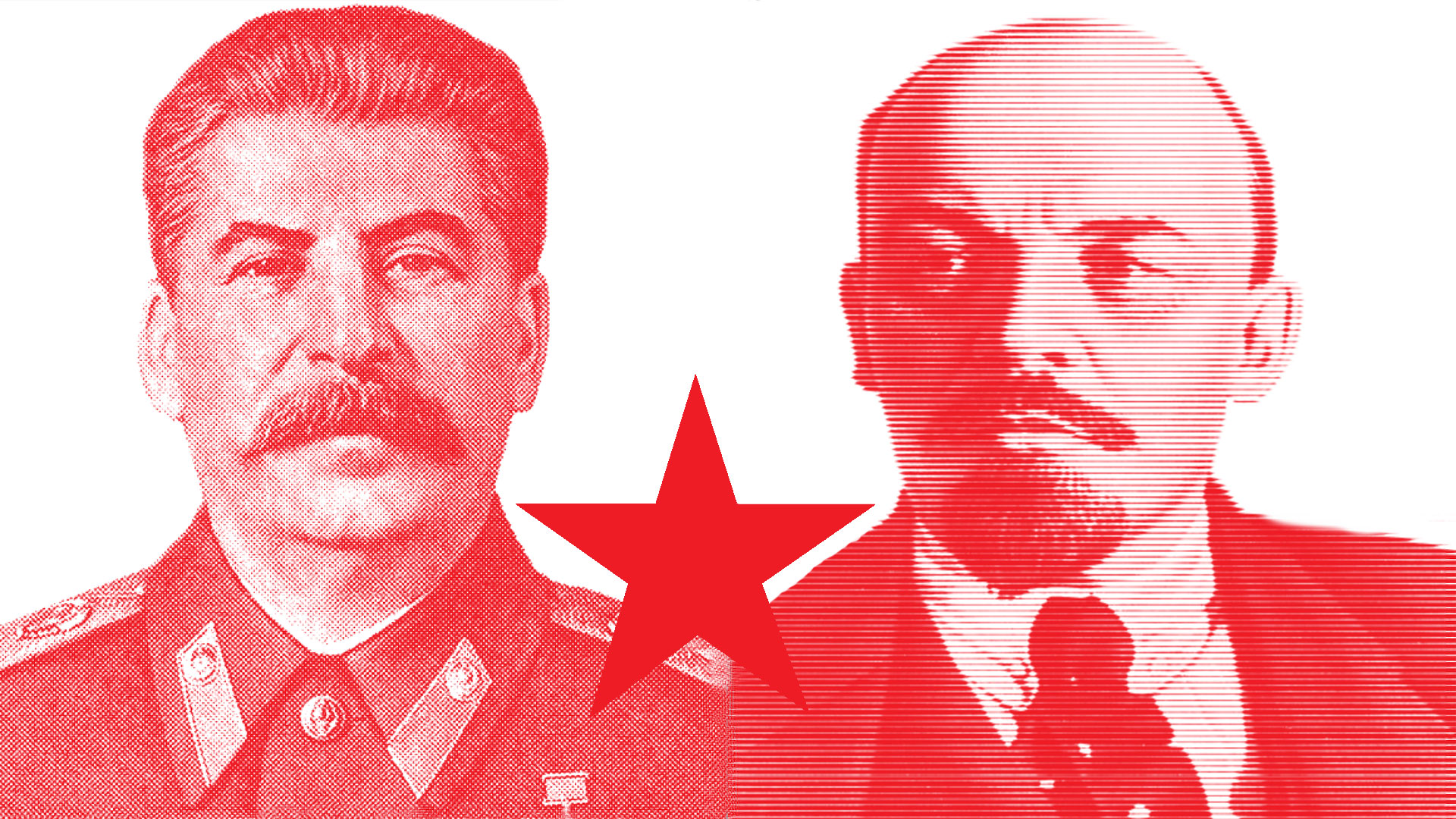

Vladimir Lenin rejected the idea of god-building; atheism was his state’s official belief system. Yet Lenin used traditional religion to secure popular support. Joseph Stalin encouraged this, turning the deification of Lenin to his own advantage as he cast himself in the role of chosen successor.

READ PREVIOUS

(PART 8)

GO TO SERIES

“Stalin is Jesus at the Last Supper, occupying the center point of the perspective to emphasize his omniscience. Behind his shoulder, a photograph of John the Baptist, in the incarnation of Lenin, hangs on the wall, looking down on the scene to bestow his blessing on his rightful heir. The anointed one is surrounded by his disciples, their heads bowed.”

This is author Deyan Sudjic’s description (The Edifice Complex, 2005) of a painting on display in an otherwise rather empty Soviet shop window during the height of Joseph Stalin’s rule. At first, the religious imagery seems strangely inappropriate for an atheistic state. Yet such was the cynical manipulation of religious sentiment in what in pure numbers was arguably one of the most murderous regimes in human history.

Hitler’s name is synonymous with genocide. By many estimates he approved the systematic extermination of 11 million innocent men, women and children, more than half of them Jews, across Europe. But Stalin was responsible for the indiscriminate deaths of roughly twice as many Soviet citizens by deliberate famine, state-sponsored terror, and exile in forced labor camps (the Gulag). Some have felt that while Hitler and his henchmen displayed brutality in the extreme, Stalin and his bestial cohorts surpassed them.

Sickening as this calculus of evil is, it explains little. It compares psychopaths in leadership roles but says nothing of the social conditions under which such men acquire and maintain power. Further, it fails to explain why ordinary people shared in their senseless brutality. While Hitler and Stalin were deranged and profoundly evil, they were aided and abetted by masses of people who moved toward them as the leaders they desired. As we have noted before in this series, the symbiosis of leader and led cannot be ignored as we try to explain the bloodlust that characterizes the rule of many, if not all, false messiahs. Nor is exploitation of religious fervor ever far from the surface as leaders seek and maintain followers. Mussolini appealed to elements of traditional Catholic religion to create his fascist cult, and Hitler was well aware of religion’s power to induce loyalty to a cause. It was no different in the atheistic Soviet Union for most of the last century.

Man of Steel

Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili was born in Georgia in 1878 (later officially altered to 1879). He was the son of peasant stock, his father a semiliterate cobbler and his mother a washer woman. Only later did he adopt the name Stalin (Man of Steel), using it consistently from about 1913 onward.

Despite his humble origins, young Joseph gained an education sufficient to admit him at age 15 to the Tbilisi Theological Seminary. But training for the Orthodox priesthood did not match his growing political leanings toward Marxism. At age 20 he was either expelled or dropped out and became involved in anti-tsarist revolutionary activities, organizing demonstrations and strikes and robbing banks. By 1912 he was living in St. Petersburg and had taken up editorship of the communist doctrinal newspaper, Pravda. His arrest in 1913 culminated in exile in Northern Siberia, but early release came with the February Revolution of 1917.

Stalin returned to St. Petersburg, renamed Petrograd, and took up his role again as editor at Pravda. The aftermath of the October Revolution later that year put him in a stronger position to advance his political career. During the two-year civil war (1918–20), he came to the fore as an effective military administrator, and election to the role of general secretary of the Communist Party in 1922 provided him the opportunity to gain influence with the regular members.

By this time the party leader was ailing. But Vladimir Lenin had little confidence in the ambitious secretary. Still, despite his deathbed criticisms of Stalin’s personality, Lenin was unable to prevent the accretion of his power.

Stalin had a very different view of Lenin. According to Georgian social-democratic leader Razhden Arsenidze, “he worshiped Lenin, he deified Lenin. He lived on Lenin’s thoughts, copied him so closely that we jokingly called him ‘Lenin’s left leg.’”

How was it that, according to Russian biographer Edvard Radzinsky, the Soviet dictator “found his god” in Lenin? Who was this man to whom Stalin owed so much?

The Father of Russian Communism

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov was born in 1870 in Simbirsk (renamed Ulyanovsk in his honor), almost 560 miles (about 900 km) east of Moscow on the River Volga. His brother’s execution in 1887 for involvement in a plot to assassinate Tsar Alexander III encouraged Lenin’s attachment to revolutionary causes. A practicing lawyer, he eventually took up full-time study and teaching of Karl Marx’s theories, mostly to the worker class in St. Petersburg. The subversive nature of his activities put him on the run from the secret police, so he changed his name to Lenin to avoid arrest. Exiled to Siberia in 1895 for revolutionary activities, he left Russia for a further five years on his release in 1900. At a 1903 meeting in London, he became head of the new Bolshevik (Russian: “majority”) faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party.

It was at about this time that Stalin became a follower of Lenin and a Bolshevik. Lenin spent little time in Russia until 1917, when, aided by the Germans, he returned from Switzerland via Germany and Sweden. The Germans hoped that his presence in Russia would destabilize their First World War enemy. By November of that year he had done just that, overthrowing the weak Kerensky government and installing the Soviet regime. As chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, Lenin soon became a dictator. Stalin was one of three key council members who supported him. Before long the proletarian revolution was in full flood, with the nationalization of banks, an end to private ownership of land and its redistribution to the peasantry, workers’ control over factory production, repression by secret police, and atheism as the state’s official belief system.

Yet, as we have seen so often in this series, the use of traditional religion played a part in securing popular support. Following an attempt to assassinate Lenin in 1918, his public persona was infused with religious verbal and visual imagery. Sociologist Victoria Bonnell notes that now the leader “was characterized as having the qualities of a saint, an apostle, a prophet, a martyr, a man with Christ-like qualities, and a ‘leader by the grace of God.’” Posters showed Lenin like a saint in Russian iconic art.

The next two difficult years saw civil war and war with Poland. By 1922, Lenin’s labors had seriously affected his health. Two strokes that year were followed by a third in 1923, which cost him the ability to speak. His first stroke did not prevent and may even have hastened his criticism of Stalin’s work as general secretary of the party and a recommendation for his removal.

An assessment of Lenin’s political career need not detain us further here. It is what Stalin did with his idol’s already existing personality cult that is significant for our purposes.

Lenin as Savior

Aspects of the political, social and religious fabric of the Russian Motherland provided many of the necessary conditions for Lenin’s cult. Historian Nina Tumarkin reminds us, “Just as the deification of Greek and Roman rulers was rooted in older conceptions of power and divinity and stimulated by current needs of state, so too later revolutionary cults were generated by political imperatives and were, at the same time, based on existing traditional forms and symbols.”

In Russia’s case, the religious pedigree includes direct descent from the Byzantine Orthodox Church of the Eastern Roman Empire. Following the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, some in Russia considered Moscow to be the “Third Rome” and inheritor of the mantle of Eastern Orthodoxy. Seeming to confirm the transfer of rights and responsibilities, the Grand Duke of Moscow, Ivan III (1462–1505), took as wife Sophia Paleologue, niece of the last Eastern Roman emperor, Constantine XI. Further, in 1547, in keeping with the Roman imperial model, the duke’s grandson Ivan IV “the Terrible” became the first Russian leader to assume the title tsar/czar (derived from the Latin caesar). Here was a monarch who was considered secular, yet also a ruler by divine right. The idea that the tsar was God’s representative on earth was soon commonly accepted among the peasantry and, as a result, easily transferable to the leader of the modern atheistic state.

The Orthodox Church’s veneration of icons and “holy” relics provided a convenient precedent for the subsequent worship of Lenin’s image and embalmed body. The purpose of this worship was, of course, that the Soviet peoples’ emotional bond with the leader should extend to the party he represented. That the bodies of saints were incorruptible was a popular notion and one that suggested Lenin embalmed would be an invaluable state asset.

As with other examples in the history of personality cults, Lenin’s elevation was evident well before his death. An important contribution came from Bolshevism itself. In its early years, the movement was anxious to replace traditional belief with a new humanistic religion—an effort known as “god-building.” The Marxist faith was to center on the physical future of man. Anatoly Lunacharsky, the self-styled “poet of the revolution” and a god-builder, believed that religion was central to all beneficial human activity. Better still if it was the religion of scientific socialism, which promised with biblical overtones “development of the human spirit into an ‘All-Spirit.’” Immortality might even be attained through the scientific defeat of death.

“It is an irony of history that the god-builders acted to deify human genius in the person of Lenin, for whom all religion was anathema. . . .”

Lenin rejected the idea of god-building on the grounds that it was just another religion based on worshiping a deity (and he was passionately against gods of any kind). But ironically it was Lunacharsky and Leonid Krasin (another god-builder) who would later supervise the embalming of Lenin and the building of his mausoleum in Moscow’s Red Square. Before that, however, in the months leading up to Lenin’s death, Stalin seized the opportunity to personally advance his hero’s cult. Inviting leaders, soldiers and workers to Nizhny Novgorod (subsequently known as Gorky for many years) to visit, pay their last respects and make promises of continued loyalty to the dying man’s ideas, Stalin cunningly set himself up as stage manager of the developing cult. As Radzinsky puts it, Stalin “devised an unprecedented propaganda campaign which might have been called ‘Departure of the Messiah.’”

Stalin knew that Russia’s history proved her need for both a god and a tsar. Accordingly, Radzinsky explains, “he decided to present it with a new god, in the place of the one overthrown by the Bolsheviks. An atheist Messiah, the God Lenin.” And though Lenin’s widow Nadezhda Krupskaya opposed the deification on the grounds that Lenin himself would have objected, Stalin was determined to have his way, making sure that she was overruled by the Politburo.

Deifying the Dead

Lenin’s funeral was a meticulously planned affair. His body arrived by train and was literally carried across Moscow to the Hall of Columns. At a memorial gathering the day before the funeral, Lenin’s widow spoke, as did various Bolshevik luminaries. Notable was Grigory Zinoviev’s address, which quoted letters from two workers. One looked to Lenin as “our dear father . . . our unforgettable father—the father of the whole world,” the other to the great leader who could not deceive the people: “It was impossible not to believe in Lenin.” It ended with the plea: “Lenin, live! It is only you who understands us, no one else.” According to Tumarkin, Zinoviev was showing Lenin to be “a prophet, and a savior.” Stalin’s speech was unremarkable except that he attempted to speak for everyone when he declared, “We swear to you, comrade Lenin, that we will not spare our lives in order to strengthen the union of the working people of the entire world—the communist international!” After Stalin’s eulogy came that of Nikolai Bukharin. He spoke of Lenin as the great helmsman who had saved the ship of state. It was a salvific image that would later become popular in Chinese communism.

“We ask that a book be published, fully comprehensible to peasants, about the life and work of dear Com. Lenin and his legacy, so that this book could be our replacement for the Gospel.”

After the memorial, Stalin stood vigil through the night as mourners filed past Lenin’s temporarily embalmed body. Requests that the funeral be postponed and even that the body not be buried at all may have meshed in Stalin’s mind with an earlier idea he had considered for establishing Lenin’s continuing presence. In any case, when the body began showing signs of decay about a month later, scientists were called upon to perform what seemed impossible at the time: embalming the body in such a way that it could go on permanent display. So successful were they that Lenin the atheist became a “holy” relic, visible to this day.

But the cult was not limited to the mausoleum by the Kremlin’s wall. Tumarkin notes, “Stylized portraits and busts of Lenin were [the cult’s] icons, his idealized biography its gospel, and Leninism its sacred writings. Lenin Corners [or “Red corners”] were local shrines for the veneration of the leader.” These took the place of the traditional icon corner in the Russian Orthodox home. In other words, the leader was immortalized. According to the All-Russian Soviet of Trade Unions, “healthy or sick, living or dead . . . Lenin remains our eternal leader.” This state of affairs led to a pilgrim industry, as thousands flocked to see the relic. It was as Stalin had planned it, but there was much more to come. Radzinsky observes, “Stalin had delivered their imperishable God. Next he must give them a tsar.”

The beginning of that transformation came at the Thirteenth Party Congress in May 1924, when Lenin’s widow provided the Central Committee with his Last Testament. The members studied it and dismissed its criticisms of General Secretary Stalin. They simply decided that Lenin’s mind was disturbed following his first stroke. This was not enough for Stalin. Knowing that his fellow committee members would oppose each other in a leadership contest, he cleverly offered to resign; after all, that was what his idol had wished. As he anticipated, because of his comrades’ bitter rivalry, he was reconfirmed. This set the scene for his rise to almost total power during the rest of the decade.

Fighting Religion and Becoming a God

The destruction of traditional religion was part and parcel of communist philosophy. Marx’s epithet, “religion is the opium of the people,” was soon promoted across the union. Priests were hounded, monasteries closed. Following Lenin’s lead, Stalin began encouraging the collective demolition of churches. What he planned in place of Moscow’s largest edifice, the Church of Christ the Savior, was instructive. It would become the Palace of the Soviets, complete with a huge statue of the new messiah, Lenin. Children were encouraged to bring traditional religious icons from home and burn them in bonfires. They were sent home with replacement posters of the beloved former leader.

“Christianity had to give way to communism and Lenin was to be presented to society as the new Jesus Christ.”

None of this, of course, prevented Stalin’s use of religious imagery. He was, after all, a former seminarian.

His religious roots showed themselves in various ways. In December 1929, Stalin celebrated his self-invented 50th birthday and combined it with the commemoration of Lenin’s death. His speech of thanks, directed “to all the organizations and comrades who have congratulated me,” mimicked humility and biblical language: “I regard your greetings as addressed to the great Party of the working class which bore me and reared me in its own image and likeness.” Here were echoes of Genesis 1, with the Party as the Creator’s replacement.

And that was not all. Like the gods of old, Stalin’s origins were other-worldly. He was not conceived and born of a woman but of the abstract Party. From a psychological perspective, perhaps this was to be expected. Though he wrote regularly to his mother, he visited her only twice in the 1920s and once in the ’30s. When she died, he simply sent a wreath. At their last meeting in 1935, he asked her why she had beaten him so much as a child. She told him that’s why he had turned out so well. Then she asked him, “Joseph, what exactly are you now?” He replied, “Do you remember the tsar? Well, I’m something like the tsar.” She responded, “You’d have done better to have become a priest.” Radzinsky notes that Pravda reported the meeting in terms of the Great Mother and the Great Leader, with imagery reminiscent of the Virgin Mary.

Stalin adopted the title “Leader”—in Russian, vozhd—in the late 1920s. It was soon applied to him uniquely, as a “leader and teacher” in the tradition of Lenin. Like other Leaders of his time, Mussolini the Duce and Hitler the Führer, he dispensed with rule by so-called democratic means once it became a possibility. Though he had begun as part of a triumvirate, by the end of his first four years in power, “the Boss” truly was well on his way to becoming a communist tsar, having eliminated all the early comrades of Lenin. And with his immediate challengers out of the way, he had gained sufficient ground to prepare for the mantle of godhood. Now he could take his place among a very different triumvirate. As Radzinsky explains, “a Bolshevik Trinity, a triune godhead, was emerging. Marx, Lenin and himself. Gods of the earth.”

Stalin seemed somewhat reluctant about his own personality cult, though he was happy enough to accept the benefits once they became evident. Analyzing Stalin’s superficial modesty, biographer Robert Service wonders if it was a lesson learned from a Roman source. “Did his interest in the career of Augustus, first of the Roman emperors, influence him? Augustus would never accept the title of king despite obviously having become the founder of a dynastic monarchy.”

“As [Stalin] became tsar he resolved also to become a god.”

Stalin’s change from promoter of Lenin as divine to the promoter of self was subtle. First he became the main interpreter of Lenin’s thought. Then he was his coequal, appearing side by side with him in posters. By the mid 1930s, Vladimir Ilyich had faded into the background of such renderings. Eventually he appeared only as a name on the cover of a book in Stalin’s hand, and the new party slogan declared, “Stalin is the Lenin of today.” Iconic images of Stalin as a Christlike figure followed. One poet wrote in 1936, “But Thou, O Stalin, are more high / Than the highest places of the heavens.” A letter written to the lower-ranking state president said, “You are for me like a man-god, and I.V. Stalin is god.” At the 1939 All-Union Agricultural Exhibition, where the Stalin cult dominated, there was even a 100-foot (30-meter) concrete statue towering over the crowds.

It is important to note once again that this evolution was not the work of Stalin alone. As in all modern dictatorships, the Leader was supported and promoted by the led. In his comparative study of Hitler and Stalin, historian Richard Overy observes, “There is an act of complicity between the ruler who projects the image of mythic hero and the followers who sanctify and substantiate it. The emotional bond created by the act binds both parties.” And of course, the support is not just for the Leader personally but for all that he does. As Service writes, “the Great Terror [1937–38] required stenographers, guards, executioners, cleaners, torturers, clerks, railwaymen, truck drivers and informers.” Thus, many ordinary people formerly skeptical of Stalin came into line. Recent scholarly examination of personal diaries from the period demonstrates the lengths to which people went to harmonize their critical views with state policy. In search of personal meaning within the awful flow of their country’s recent history, they explained away what their minds were telling them was wrong. Cultural historian Jochen Hellbeck shows that under such conditions, people will rationalize terror, cruelty, deprivation, false imprisonment and purges of family and friends to feel at one with the system. People want to have lives with meaning, and the communist project seemed to provide that: humanity was on its way to socialist perfection; the “new man” was being formed.

Power, Peoples and Purges

Once Stalin had achieved sufficient power, he set about effecting “the Great Change.” Convinced of the Leninist dictum that terror is an essential instrument for legitimizing the state, and with the murderous tsar Ivan the Terrible as his model, he launched an attack on those farmers and their families (the kulak) who had profited under the New Economic Policy (1921–28).

In 1929, Stalin made his intentions plain when he wrote about “the liquidation of the kulak as a class.” Starting that year, they were shipped out to remote frozen wilderness areas by cattle car and left to fend for themselves. Their removal, together with Stalin’s collectivization of agriculture and acceleration of industrialization, left the countryside desperately short of food. This led to horrific examples of cannibalism and the death by famine of an estimated 5–8 million people. Yet Stalin dismissed talk of famine as “counter-revolutionary agitation.” In the cities there was hatred of the starving kulaks who appeared on the outskirts like desperate foraging animals.

At the same time, Stalin began political purges with the supposed aim of protecting the Soviet experiment from Western imperialist “wreckers.” He took the opportunity to stage show trials of intellectuals, academics, scientists, economists, as well as political opponents. When his lieutenant S.M. Kirov was murdered in 1934, Stalin even purged many of the “Old Bolsheviks,” men with whom he had worked and governed.

In early 1937, the Great Terror took hold. The Politburo sent out the order to local authorities to exterminate “the most hostile anti-Soviet elements.” According to British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore, this amounted to “democide,” ordering the death of entire classes of people by “industrial quotas.” He notes, “This final solution was a slaughter that made sense in terms of the faith and idealism of Bolshevism which was religion based on the systematic destruction of classes.”

The operation was so successful that the local authorities, with their three-man tribunals, asked for higher quotas and got them. In all about 760,000 were arrested and almost 400,000 executed. These indiscriminate arrests and killings were augmented by the national and ethnic murder, arrest or deportation of large numbers of Poles and Germans, as well as Bulgarians, Macedonians, Koreans, Kurds, Greeks, Finns, Estonians, Iranians, Latvians, Chinese and Romanians, bringing the total arrests to 1.5 million and the death toll to 700,000.

Stalin, the mastermind behind all of this appalling death and destruction, disappeared from public view while the killings were going on. At the same time, he took the chance to rid himself of many people closest to him. Montefiore notes: “Within a year and a half, 5 of the 15 Politburo members, 98 of the 139 Central Committee members and 1,108 of the 1,966 delegates from the Seventeenth Congress had been arrested.” Wives of the condemned were imprisoned and separated from their families. Almost one million children were thus deprived not only of their fathers but also of their mothers, many for up to 20 years. Even the secret police and army were not immune, with one chief after another suffering the same fate: beaten into confession for treasons they never committed, and shot on the Boss’s orders. Anyone suspected of potential disloyalty to the state in the event of world war became a target.

When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Stalin was stunned, but he quickly recovered and took matters in hand. His subsequent wartime leadership meant a massive increase in suffering and numbers of dead, though the internal terror abated. Despite Allied victory over Germany, more than 20 million died in the USSR, of which about 7 million were civilians. Stalin’s willingness to sacrifice his people had not changed. Nevertheless, he was voted Marshal of the Soviet Union (1943) and Generalissimus (1945).

Despite the carnage in his wake, his elevation continued. In the conclusion to a 1949 Soviet film, The Fall of Berlin, Stalin arrives in the ruined city by air. Wearing a shining white uniform, the messiah is welcomed by the happy people of the world. They sing, “We follow you to wondrous times, / We tread the path of victory. . . .” Yet soon his paranoia about the West, and about imperialist enemies within, returned. There were more purges and the persecution of those closest to him.

Stalin’s death in March 1953, following a cerebral hemorrhage, made him even more the subject of adulation. Thousands streamed past his body, lying in state in the Hall of Columns. Embalmed in the manner of Lenin, he was laid to rest at his former idol’s side in the Red Square mausoleum. Only in 1961, five years after Nikita Khrushchev’s public repudiation of Stalin’s cult, was the disgraced leader removed and buried near the Kremlin wall. He had promoted Lenin’s cult in an effort to advance his own apotheosis, and for a bloody three decades he had succeeded. But in the end he was brought down to the ground quite literally. And Stalinism was buried with him.

As for the man whose crucial testament Stalin had suppressed, he is still on display—a moribund reminder of his own false messianic system. Overwhelming malice and brutality meant that neither Lenin nor Stalin could ever deliver anything approaching utopia.

Next time, the 20th-century false messiahs of the Orient.

READ NEXT

(PART 10)