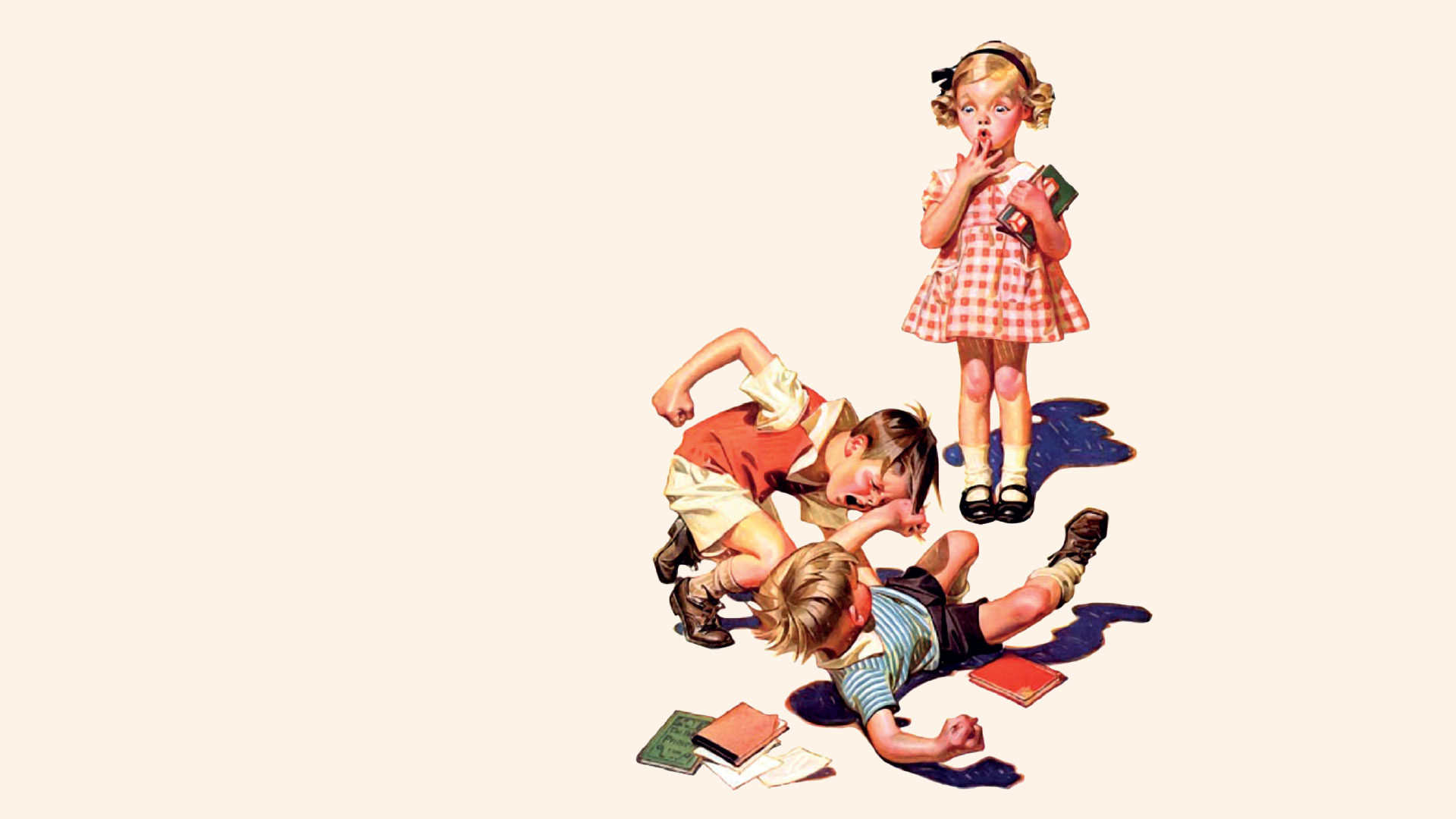

My Brother’s Keeper: From Sibling Violence to Brotherly Love

As recently as the 19th century, Western societies lived by an unspoken pact: what happened in the family stayed in the family. Scandal, and even violence, was nobody else’s business and was best hidden from the public so that the illusion of wholesome, happy and healthy family relationships could be maintained.

Gradually, however, cracks began to appear in society’s veneer, and the image of the modern flourishing family gave way to a more nuanced portrait. First, seemingly isolated incidents of child abuse intruded on public awareness, prompting the establishment of a society for child protection in America by 1875, and a similar society in Britain by 1884. The exposure of marital violence was less forthcoming despite the efforts of early women’s movements. Nearly a century passed before the first shelter for battered women opened in England and its founder, Erin Pizzey, published Scream Quietly or the Neighbours Will Hear (1974), which would spread awareness of domestic violence across Europe. The next year, British geriatric physician G.R. Burston described a phenomenon he called “granny battering,” corresponding to what American practitioners had been calling “battered old person syndrome.”

“Headlines exposing violence in families appear repeatedly in our newspapers and on television. They appear so frequently that we have almost become immune to them.”

But there was yet another skeleton to be discovered in the family closet. In 1980 a groundbreaking study, known as the National Family Violence Survey, would be published in the United States under the title Behind Closed Doors: Violence in the American Family; it would reveal that—of all forms of family violence—the most prevalent was that which occurs between siblings.

This discovery remains well worth looking into, because despite reductions in birth rates throughout much of the world, the majority of children have brothers and sisters. Even in China, single-child policies have not been widely implemented outside urban areas. And rather than being immune to sibling violence, single children may suffer indirect but significant effects, since those who are violent toward siblings also tend to be violent toward dating partners and peers.

But what is sibling violence? Don’t all children quarrel and even fight occasionally? Isn’t it an overreaction to classify aggressive behavior between siblings as violence? Where is the line between “normal” sibling conflict and abusive behavior, and how and when should parents intervene?

Oddly enough, despite the surprising finding of the National Family Violence Survey, these questions went largely unconsidered for some time by researchers in their understandable zeal to study forms of domestic violence that had already been accepted as social problems. Sibling violence was easily shrugged off as little more than an exaggerated form of sibling rivalry, a concept that in some circles is considered “Darwinian common sense.” Sibling aggression, bullying and even murder, after all, are certainly not unusual in nature, where in some species the wild young compete to the death for the sole right to the survival resources provided by their parents. Thus the terms “sibling” and “rivalry” were nearly inseparable for decades, particularly in Western cultures, forming the basis of perhaps the most popular view of the sibling relationship.

“It is difficult to determine where normal developmental behavior between siblings ends and abuse begins. Normal sibling rivalry and conflict is often characterized by interaction that leads to healthy competition without anyone getting hurt.”

Interestingly, the first crime described in the Bible is fratricide: a jealous Cain kills his more successful brother, Abel, and when asked his whereabouts, Cain disdainfully responds, “I don’t know. Am I my brother’s keeper?” Clearly he thinks not.

Later in the same book, Genesis, a younger brother (Jacob) cheats his older brother (Esau) out of his inheritance, and a few short chapters farther on, Jacob’s older sons throw their paternally favored brother, Joseph, into a pit and conspire to kill him. In a twist that hints at the complexity possible in sibling relationships, one of the brothers, Reuben, hatches a private plan to return and save Joseph, but he is unable to intervene before the others sell the boy into slavery. Joseph ultimately repays his brothers with kindness, saving their lives in the face of drought and almost certain starvation. But it is the early rivalry between them that tends to be remembered, reinforcing commonly held stereotypes about the nature of sibling relationships.

At the other extreme, the relationship between twins has enjoyed a far more benign reputation. Stories abound of seemingly telepathic twins whose bonds—spiritual and physical—were forged in the womb, who enjoy a harmonious mind meld of the kind that is assumed to be forever beyond the reach of ordinary siblings not fortunate enough to be endowed with a real-life mirror image.

The reality, of course, is that twins can be plagued by competitive and even violent relationships just as singletons can enjoy warm, supportive bonds. But it was perhaps not until Stephen P. Bank and Michael D. Kahn published the 1982 edition of The Sibling Bond, a collection of their research into the complexities of sibling interactions, that these polarized stereotypes were seriously challenged by researchers. Further, Bank and Kahn’s contention that parents are not actually a child’s only significant influence inspired later researchers to explore the rich variety of emotional, developmental and other needs that sibling relationships can fulfill, leading many to regard brothers and sisters as potentially important attachment figures—different from parents, but no less influential. As we will see, the findings of these studies in terms of the influence of sibling relationships on personality development and even resilience raise serious questions about whether and how far parents should tolerate conflict and aggression between their children.

The same body of research also underscores that it isn’t enough for parents to discourage negative interactions between siblings. Just because children don’t lash out at one another overtly doesn’t mean they feel warmly toward one another—and it’s the degree of warmth in a sibling relationship rather than the mere absence of negativity that predicts children’s behavioral, emotional and social adjustment. This isn’t to say that children who feel warmth toward one another will never experience conflict, of course; the goal for parents is to help children increase their ability to resolve conflict reasonably quickly and restore an atmosphere of active support. This may require parents to change their expectations: instead of brushing off hitting, name-calling and shunning as harmless behaviors, parents ideally would make it clear that they expect their children to treat each other with warmth and affection, and would reward such behavior when it occurs spontaneously.

“When parents lack a stable value system by which to settle sibling disputes, or when their principles are capricious, bizarre, or arbitrary, the sibling relationship can become chaotic or even murderous.”

Obviously it is in a parent’s best interest to aim for this: few parents take pleasure in presiding over constant squabbling. More important, it’s in the children’s best interest too. Sibling relationships are likely to be the most enduring they will have in their lifetime. Like our parents, siblings are party to our early experiences, but barring unnatural death, they are likely to remain part of our lives much longer, outliving parents by 20 years or more. In addition, if siblings share both parents with us, we will typically have about 50 percent of our DNA in common. That means they are genetically more like us than anyone else on earth other than our parents. Considering that these relationships can contribute tremendously to the stores of resilience that will help carry us through the adverse events that are an inevitable part of life, it makes sense to ensure that they are as supportive and nurturing as possible. Fortunately, research suggests that even though there will always be some elements outside their control, parents are capable of exerting a powerful influence over whether their children will develop positive or negative relationships, either of which can have a lasting effect on the child’s worldview and corresponding mental health persisting long into adulthood.

The Roots of Discord

Why is violence so widespread among siblings? In large part, such behavior is rooted in the many harmful stereotypes that cloud parents’ understanding of the boundary between healthy and unhealthy sibling relationships. Not only do many parents view altercations between children as minor, but some see them as a necessary and beneficial preparation for “real life.” Mounting research contradicts this assumption, however. It is true that children can learn a great deal about how to resolve conflict as they interact with their brothers and sisters, but the necessary skills do not come automatically. When parents fail to set clear boundaries and intervene appropriately, “ordinary” conflict can develop into chronic aggression, which in turn can escalate into violence.

Sibling violence includes a variety of abusive behaviors, and while it may not always be easy for parents to recognize the line between normal developmental conflict and abuse, researcher and psychologist John Caffaro offers a helpful guideline: “Violent sibling conflict is a repeated pattern of physical or psychological aggression with the intent to inflict harm and motivated by the need for power and control,” he says, noting that psychological attacks are frequently at the core. “‘Teasing’ often precedes physical violence and may include ridiculing, insulting, threatening, and terrorizing as well as destroying a sibling’s personal property.” Often one sibling (not always the oldest or biggest) consistently dominates in these conflicts, and the weaker or more passive child, having failed at all attempts to stand up to the aggression, will cease to resist in what researchers call “learned helplessness.”

Bullying perpetrated by brothers or sisters can be considerably more traumatic to children than peer bullying, because it occurs within the home on an ongoing basis and there is often no way of escape—and very little respite—for the sibling on the receiving end. According to family violence researcher David Finkelhor, such a situation can be every bit as harmful to a child’s well-being as other forms of abuse, elevating trauma symptoms and making children more susceptible to future victimization rather than preparing them for healthy peer relationships as parents may assume. The bullying sibling is also susceptible to a variety of negative outcomes, possibly in connection with the same lack of parental supervision that enables his or her negative behavior toward brothers or sisters. These have been found to include substance abuse, academic difficulties, anxiety, depression and continued violent relationships throughout life. Sadly, violence between siblings also sometimes turns deadly. When this happens, parents experience the loss of both children, not only the victim.

As one might expect, poor overall family functioning is highly associated with sibling conflict and violence. Researchers still have a long way to go in isolating all of the relevant family factors, but some of the most prevalent include parental conflict, parental neglect or abuse of children, and preferential treatment. The first two may seem more intuitive than the last. Certainly it would seem obvious that parents who lack constructive skills for resolving conflict are not going to be well prepared to either teach or model them to their children. And it’s easy to understand why children in abusive homes learn that aggression and violence are acceptable approaches to addressing problems. But can preferential treatment really be all that harmful? In fact, it is one of the most damaging of all the influences on sibling relationships, and one of the most common mistakes parents make.

Of course, there are still other dysfunctional dynamics that may be acting together in families plagued by sibling conflict. Robert Sanders, recently retired from a position as professor of social sciences at Swansea University in Wales, has extensive experience in working with children and families. In his 2004 book on the subject of sibling relationships, he summarizes that “factors such as the child’s temperament, the level of positivity in the relationship between the parent and children, differential negativity in the relationship that the parent(s) has with the children, and the level of conflict between the parents, all combine to influence the quality of the relationship between siblings, which may prove quite consistent over time between middle childhood and early adolescence.” While all these factors could theoretically be modified, often they are not: patterns of behavior in dysfunctional families tend to remain static unless someone or something becomes a catalyst for change.

Sowing Sweet Harmony

Modulating from discord to harmony in children’s relationships may not be the easiest task a parent will undertake, but it may be one of the most rewarding—for parents as well as children. In fact, family studies researcher Laurie Kramer suggests that strengthening these relationships may be a key strategy for enhancing resilience for the rest of the family too. Warm, affectionate sibling relationships have proven very beneficial as siblings pass on positive life skills to one another by example through their social interactions. Evidence increasingly confirms that such relationships help children adjust to stressful events by providing a sense of identity, comfort and resilience, even when children face critical situations such as parental conflict or divorce, or placement in foster care. And although we tend to think of sibling relationships in terms of our childhood years, the benefits do not end when we leave home. Health and well-being in later life are also enhanced by high-quality early and continuing sibling relationships.

What does this mean for parents who hope their children will enrich one another’s lives rather than cripple them?

Besides making sure that adults in the family are modeling appropriate behavior, there are many ways parents can actively encourage cooperation and warmth between children. Among the most important is to provide children with access to one another, to allow recreational time, and to provide supervision appropriate to the children’s needs and interpersonal skills. Childhood play provides bountiful opportunities for siblings to interact in supportive ways. “In fact,” writes Kramer, “the experience of having fun together is important as it strengthens the sense of cohesion and solidarity that children need to form a supportive relationship that will endure over time.” It is also a perfect opportunity for the development of social skills and behavioral and emotional regulation as they navigate their often complex fantasy-play scenarios. “This ability to develop such a shared understanding—even if it is simply within the world of play—may be one of the rudiments of sibling support,” Kramer adds. And while conflict may arise fairly often in childhood play, this is not necessarily an indication of the quality of the sibling relationship. Rather, it seems that relationship quality is related most strongly to children’s ability to resolve conflict and manage emotions—skills parents certainly can (and should) teach. (See our interview with Dr. Kramer.)

Unfortunately many parents are not sure how to teach this, and as a result they often make any of several common mistakes: They may become referees, planting themselves squarely in the middle of every conflict to determine the winners and losers—which only sets parents up to be required to repeat the same pattern endlessly. They may refuse to hear both sides and/or punish both children in the mistaken belief that this will help them learn to work things out on their own. Unfortunately, these strategies may only drive the children’s behavior “underground,” where they can be played out through bullying behaviors. Alternatively, some parents may even encourage conflict, either overtly or through failure to monitor and intervene when one sibling is clearly running roughshod over another.

In contrast, effective parents use conflict to teach children the moral principles behind resolution strategies and to demonstrate how to apply these principles. Violent, abusive or humiliating treatment is not tolerated by these parents, and they establish consequences for behavior that violates those values that support active concern and respect for others.

Ongoing Involvement

While parents may find that their direct monitoring or coaching is needed less often as positive interpersonal skills are successfully developed, a study published in the August 2000 issue of the Journal of Marriage and the Family emphasizes the need for parents to continue to spend quality time with the sibling group, even into adolescence. These researchers note that time spent together as a family may be a reflection of the quality of family cohesion, which is, not surprisingly, linked to positive sibling relationships. Just as parental supervision has a positive influence on younger children’s peer relationships, they speculate that “in adolescence, the presence of a parent—as a companion, model or supervisor—also may turn siblings’ attention away from bickering and teasing.”

Of course, for their involvement to be effective, parents need basic positive-parenting skills, and they must practice what they preach. To try teaching what is unfamiliar is to fight a losing battle. If sibling relationships seem to be characterized by bickering, sarcasm, rivalry and competition, it may be time for parents to ask themselves some searching questions: Is my children’s behavior simply a reflection of the behavior they see in me? Could I be encouraging competition through preferential treatment or by comparing one child to another? Do I help each of my children identify his or her unique strengths, and notice and reinforce their efforts to do well?

For good or evil, it is our nature as social beings to look for approval from those who are important to us. We learn best from those we love, and we look for feedback that tells us we are succeeding in their expectations of us. “All children feel hurt and angry when they try hard to accomplish something that is difficult for them but receive no recognition for their efforts,” says child and family therapist Peter Goldenthal. “The anger is often directed at their brothers and sisters.” This is particularly likely if their siblings easily excel in an area where they struggle, and the problem is compounded when parents make comparisons between their children. Understanding each child’s unique strengths and weaknesses is the first step toward meeting their individual needs and helping them reach their full potential, while also reducing the fuel for conflict. And there is another benefit to doing so. The beliefs and values of parents are contagious. As we learn to love and appreciate each child uniquely, and respond to their needs without partiality, we are likely to find that our children will mirror our outlook, appreciating one another’s differences while also enjoying areas of shared interest and identity. They are also likely to influence and support each other in ways that will contribute to their personal development, strengthen their ability to cope with adversity, and enrich their lives.

This, of course, is what most parents hope children will achieve in all of their relationships, but particularly with their siblings if they have them. We know that it is within these intimate relationships that our children will establish their first and closest potentially lifelong bonds. We also hope that our children will outlive us, and ideally we would like the supportive bonds between them to outlive us too.

Parents may not be able to guarantee this outcome. Nevertheless, as the research indicates, they can do a great deal to increase the likelihood that sibling relationships will not be characterized by competition, aggression, envy and violence, but by cooperation, altruism, respect and love.

Every sibling relationship is likely to undergo changes in styles of relating and frequency of contact. But children’s understanding of their family’s values and expectations should lead them to be able to answer the question “Am I my brother’s keeper?” unequivocally in the affirmative.