The Middle East and World War I

Events in the Middle East continue to feature in world news as they have for more than a century. Like iron filings in a child’s first magnetic puzzle, they draw in nations from all directions. None, it seems, can resist getting embroiled in what has been called “the cockpit of national identities and perpetual conflict.” Often the focus is narrowed to Israel and Palestine; now it is John Kerry’s turn to attempt an American-brokered “just and viable peace.” In the carefully scripted language of diplomacy, according to this secretary of state, all issues are “on the table for negotiation. And they are on the table with one simple goal: a view to ending the conflict.”

Like so many problems in the Middle East, this impasse has some of its roots in World War I. With the opening shots of that devastating war, the stage was set for European and American involvement that has lasted until now. In all the ups and downs of more than a century of bloodshed, ceasefires, negotiations, broken promises, misappropriation of land and meaningless loss of life, it is the ordinary people of the Middle East who have suffered most.

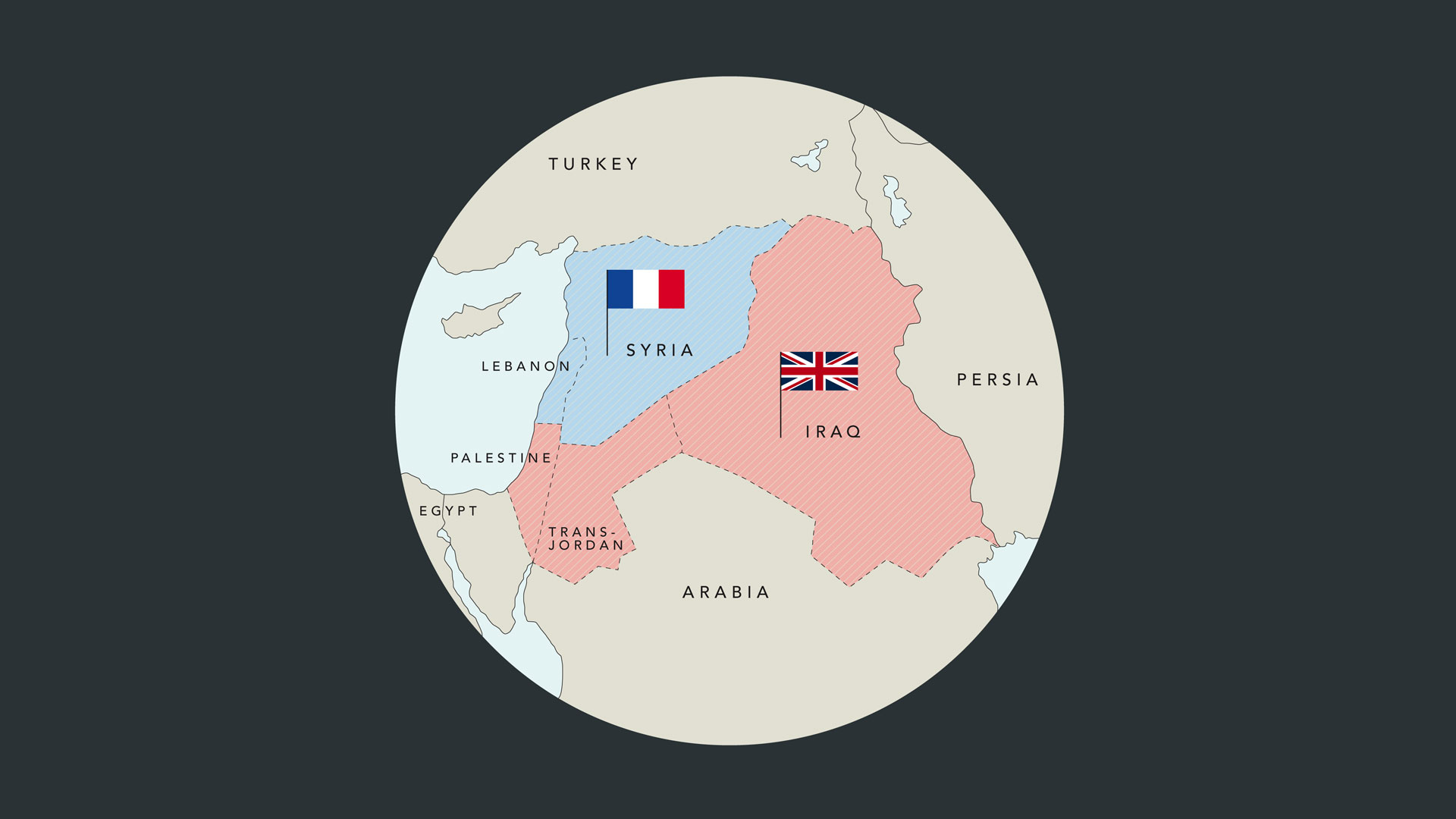

Colonial-era power plays between the rival British and French governments were evident during the war. In 1916, anticipating not only victory over the German-Ottoman alliance but commercial gains for themselves, they signed the Sykes-Picot Agreement on a new Arab confederation, but they kept it secret from the Arabs. At the 1920 San Remo Conference, Allied powers decided the future contours of the Middle East: France would have mandatory control over Syria and Lebanon, Britain over Palestine and Mesopotamia.

Why did they want control of this vast Arab-populated territory? Each was still expanding its empire and trying to prevent the other from gaining advantage. Certainly the actual and potential oil resources of the area were a factor, meaning that any railways and pipelines would have to be in safe hands. For Britain, the strategic importance of Egypt’s Suez Canal to her imperial possessions in the east—including India, “the Jewel in the Crown”—provides another part of the answer. Possession of Palestine, adjacent to Egypt, became a central factor.

It’s well known that the British government also came to an understanding with the Jewish community in Britain, enshrined in the 1917 Balfour Declaration. As postwar mandatory power, the government would support the establishment of “a national home for the Jewish people,” provided that nothing would be done to “prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.” This document, perhaps intentionally ambiguous, has been the source of much of the acrimony between Palestinians and Israelis and more broadly between Arabs and Jews. It lent support to political Zionism, central to the establishment of the State of Israel.

“The way of peace they have not known.”

World War I, often referred to as the war to end all wars, has cast a long shadow over the past hundred years. It seems that its treaties were too often attempts at peace that ended all peace. In the Middle East, the turmoil continues. Is there a solution beyond the endless bids for a “just and viable peace”? It can come only from without; of ourselves we can’t change to the degree necessary to end all war. Two thousand years ago, the apostle Peter told a Roman centurion and his household that the peace he represented was available to all who fear God and do what is right, that “God shows no partiality”; this was “the word that he sent to Israel, preaching good news of peace through Jesus Christ [the Prince of Peace]” (Acts 10:34–36, English Standard Version). We can do no better than that.