The Baby Business

Hidden Motives and Costs of Reproductive Tech

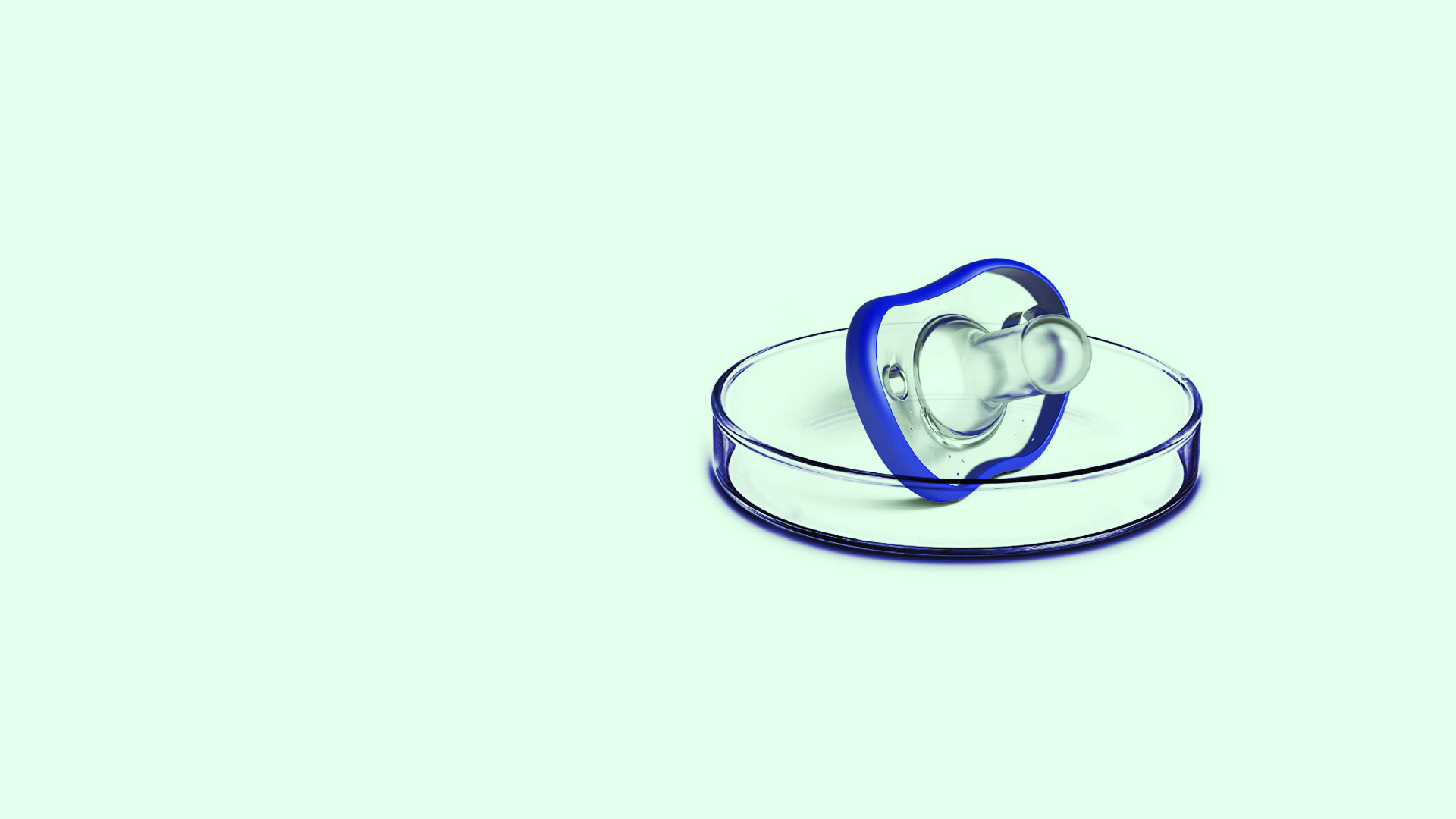

For the relatively few couples who experience infertility, in vitro fertilization is the only way to conceive a baby. So why are so many others also using assisted reproductive technologies? Two excellent books discuss the impact of IVF and embryo screening on the future of family and society.

The Pursuit of Parenthood: Reproductive Technology from Test-Tube Babies to Uterus Transplants

Margaret Marsh and Wanda Ronner. 2019. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 274 pages.

Fables and Futures: Biotechnology, Disability and the Stories We Tell Ourselves

George Estreich. 2019. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. 219 pages.

Wanting a baby is a natural thing, but sometimes to “be fruitful and multiply” doesn’t happen so naturally. In vitro fertilization (IVF) gives nature a nudge by bringing egg and sperm cells together outside the body. The process is becoming so common that spelling out the acronym is nearly as unnecessary as spelling out “NASA.”

Since Louise Brown’s breakthrough birth in 1978, we are now closing in on the 9 millionth IVF child. Worldwide each year, more than 2 million IVF cycles are conducted. These are neither simple nor inexpensive.

A typical path to initiate a baby goes like this: A woman receives hormone injections to stimulate ovulation of multiple eggs. The maturing eggs are plucked from the ovaries by means of a needle connected to a suction device. In a lab, embryologists observe the condition of harvested eggs and mate the best with carefully screened sperm cells. They may freeze extra sperm and unfertilized eggs for later use. The fertilized eggs divide and grow in a small incubator for several days.

Next, in many cases, embryos undergo genetic evaluation. Preimplantation Genetic Testing (PGT) involves examining the genome/DNA of a cell biopsied from the developing embryo to determine chromosome abnormalities, single-gene diseases and other traits. For parents who are carriers of a genetic disease, PGT has been a godsend, screening out affected embryos before implantation. But what gets screened out is a moving target. Down syndrome, gender, and in fact any trait that’s pegged to a DNA sequence could be used as a marker for deciding whether an embryo is suitable for implantation. And of course, as germ-line editing and trait manipulation expand in the future, those embryos will of necessity be evaluated to ensure that the expected alterations have succeeded.

Finally, one or more embryos are introduced into a uterus—either the woman who is the biological source of the egg or a gestational surrogate. (Potential parents may also use a donor’s eggs and/or sperm rather than their own.) The overall success rate is currently estimated at 30 percent or less. But if all goes well, an embryo will implant itself into the uterine wall, and nine months later, this Rube Goldberg sequence will result in the birth of a new family member.

Like leftover sperm and eggs, any remaining embryos may be frozen as a kind of fail-safe should pregnancy not occur. Determining exact numbers is impossible, but with more than 280,000 IVF cycles performed in the United States in 2017 alone (according to the most recent figures from the US Centers for Disease Control), some estimate that a million or more leftover embryos are now being cryogenically preserved across the country. Following a successful pregnancy, the fate of these embryos is tenuous—adoption? abandonment? use in research?—and their preservation is expensive.

About 500,000 babies are added annually to the global population using what is broadly called Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART). When viewed in the context of more than 130 million babies born every year, this is not an especially large number. But there’s growing concern that IVF will lead to a new kind of engineered humanity, a new kind of family planning. In some ways, it already has.

While IVF has been a miracle for those dealing with infertility, it reaches well beyond that. As a window into an embryo’s genetic condition, it provides a way for parents to select against debilitating diseases, but also to make choices about such traits as gender, eye color or even lactose intolerance. The more we learn about the human genome, the longer that list will grow. What’s more, as a platform for genetic intervention through gene editing, IVF becomes a possible route to genetic enhancement—at least, for those who can afford it.

IVF also allows a woman to hit the snooze button on her biological clock. Combined with egg extraction and freezing, she can postpone parenthood and pursue a professional career or other goals that are more easily achieved child-free.

The Wild West of ART

As we labor toward reproductive independence and genetic control, couples, singles, scientists and historians are asking important questions: Should egg freezing and IVF become the normal way to control the timing of conception? How will we decide which embryos to discard as abnormal? Are the words disease and disability interchangeable? What will be the role of government regulation?

In The Pursuit of Parenthood: Reproductive Technology from Test-Tube Babies to Uterus Transplants, social historian Margaret Marsh (Rutgers University) and gynecologist Wanda Ronner (Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania) argue that we must think carefully about the societal reasons for practicing ART more widely. In their view, the United States in particular is a largely unregulated “Wild West,” and they insist that “an unregulated marketplace in reproduction does not serve this country well.”

“We may not have a crystal ball to foresee exactly what form a good regulatory system in this country would take, but if we do not begin now, we will likely be unable to tame the Wild West of reproductive medicine. . . .”

The problem, they explain, is a political history that has put medicine in the hands of the marketplace. “We are now four decades removed from the decision of the administration of Jimmy Carter to ignore rather than to grapple with the ethical and political ramifications of the creation of human embryos outside a woman’s body. The technologies have multiplied. So have the medical and ethical questions about them.”

They note that “in this country, ethics commissions come and go. Recommendations for national policies from bioethicists and others fall on deaf ears in Congress.”

Marsh and Ronner observe that congressional reluctance to develop IVF regulations arose from the politics of abortion. Its legalization in the 1973 Roe v Wade decision made reproductive medicine a third rail—untouchable, too politically charged to approach. As a result, studies involving human embryos were banned from receiving federal research grants; moratoriums were enacted and never lifted. While the rest of the world created rules and regulations that allowed IVF medicine to evolve under government oversight, in the United States researchers turned to private funding, and private funding has led to commodification of IVF and ART.

Divided by arguments over such issues as abortion, gender equality and definitions of family, Marsh and Ronner write, the United States “has by default allowed the market to determine the development of and access to assisted reproductive services.”

Patient and Consumer

Because for-profit fertility clinics drive and sell ART services in the United States, they’re always in pursuit of new and repeat customers. Whether playing the drumbeat of the biological clock, pressing the need to avoid genetic disease, or appealing to the power of a woman to exercise her reproductive independence, clinics market to all women as potential consumers of their product. “Twenty-first-century reproductive medicine has flourished in the private sector,” Marsh and Ronner explain, “. . . because patients generally pay for IVF and other advanced technologies out of pocket, and IVF centers can be highly profitable.” Market researchers predict that the global market for IVF by 2024 will be $40 billion—a $19 billion increase from 2018.

Consistent with the authors’ respective fields, The Pursuit of Parenthood tracks the historical development of ART with a focus on the life and health concerns of women. It’s as much about social equity as it is about pursuing a family; and it shows that, unfortunately, we are not very good at either. The solution begins, they insist, with reproductive health care that is neither subject to the whim of the government nor at the mercy of the marketplace. “The two of us believe that just as health care is a human right, fertility care should be considered part of a woman’s basic health care.”

Marsh and Ronner leave the reader wondering whether we have created a techno-fix for social dysfunction—and a deceptive one at that. Egg freezing, for example, has been sold to young women not only as a way to save one’s eggs prior to treatment for diseases such as cancer, but also just to postpone having a family. The pitch, they write, has been that a woman’s “fertile years were slipping away.”

And it has worked. As 30-something journalist Natalie Lampert enthused recently in an NBC Think article, egg freezing, IVF, career and lifestyle planning all naturally go hand-in-hand. “For a certain group of women,” she writes, “egg freezing has proven to be an empowering tool, transforming women’s personal lives in profound ways by offering a sense of independence here and now, as well as peace of mind in terms of family in the future.”

That “certain group of women” are clearly young and wealthy. Still, at least one ob-gyn insists that egg freezing “should be on the radar of every woman in her 20s,” calling it “an insurance policy for your reproductive health.” But it will be an expensive “policy,” currently ranging from around $6,000 to $20,000. With a basic IVF cycle costing an additional $10–20,000 (genetic screening and/or gene editing could add thousands more to the tab), the question of who will actually be able to participate in this new world of family planning looms large. Even for those who can afford it, a successful pregnancy is far from a sure thing.

This reality, despite the implicit optimism put forward by fertility marketers, is one of The Pursuit of Parenthood’s strongest warnings. The unspoken moral to these stories, the authors say, is “Spend tens of thousands of dollars to freeze your eggs, and you may easily end up poor and infertile.” That’s because “even for young women, egg freezing offers no promises.”

Social Engineering

Overall, The Pursuit of Parenthood argues that we are not engineering the right things: “We see not a word about reengineering marriage as a more egalitarian partnership, or reengineering the workplace and the larger society to provide the kinds of structural supports that would allow women to have their children earlier and still have a thriving career.”

The authors bring an important focus to these challenging problems. While their book applauds the science that has increased women’s reproductive choices and laments the social barriers stunting feminine progress, it doesn’t delve deeply into some of the newest aspects of genetic control; for example, the evolving uses of embryo screening and germ-line editing using technologies such as CRISPR, and increasingly pressing questions about embryo selection.

Marsh and Ronner are certainly not ART Luddites. They believe “it is a doctor’s role to prevent suffering” and that using these technologies for that purpose isn’t the same as creating a designer baby. They also acknowledge a tension between what should be eliminated and what should not. How do we define suffering? Should we eliminate an embryo because it—or the parents—will likely suffer in some way?

“Disability rights advocates have argued that the desire to have a child free of a genetic disease could lead to the devaluation of the lives of those who are living with a disability. This concern should be taken seriously.”

Defining Disability

“I am in between an old way of doing things and a new way, as many of us are,” writes George Estreich in Fables and Futures: Biotechnology, Disability and the Stories We Tell Ourselves. “But the species, too, is in between an old way of doing things and a new way, between the past of Ordinary Human Reproduction and the digitally assisted forms now underway.”

An instructor in the School of Writing, Literature and Film at Oregon State University, Estreich isn’t an expert in science, fertility or bioethics. But his daughter, Laura, was born with Down syndrome, so he brings a unique perspective to discussing how best to use the technologies that could eliminate it. “I’m deeply pro-science,” he writes. “But if our new biotechnologies are to help us, we must see them clearly—and we must also recognize that, as currently constituted, they reflect and amplify our misconceptions about disability and our devotion to the often-destructive idea of ‘normal.’”

In Fables and Futures, Estreich takes a deep dive into questions of human relationships that Marsh and Ronner necessarily pass over. They acknowledge the “devaluation” of disabled people, but to Estreich, it’s real. Many writers talk about the science of genetic possibilities and the potential to eliminate disease, but most of them write from the head; Estreich writes from the heart. After all, eliminating genetic disease would have meant eliminating Laura.

This is a must-read for anyone interested in the possible consequences of ART. While Estreich focuses on Down syndrome, his arguments connect back to IVF and, in particular, embryo screening. What if a couple wants boys instead of girls? All their female embryos would remain frozen, bypassed in favor of those carrying a Y chromosome. That kind of parental selection is allowed, because the distinction between disability and desirability is malleable and will only become more so in this new age of genetic inspection. Fables and Futures helps us think about the choices that are before us, and about those to come.

A Person or a Projection?

What do we see when we notice someone with a disability? Estreich says it’s often what we expect to see—a projection of our own bias and judgment, even of our imagination. People would inevitably stare at the “huggable ghost” that was his daughter—“a vague shape, a diagnosis with a personality, a mix of sweetness and tragedy, of angels and heart defects and maternal age.”

“That is a way of imagining Down syndrome, and not the worst way, but it hides the individual. The projection, the ghost, obscures the child.”

That we harbor bias is a hard reality to understand and admit, but it’s a key insight if we’re to find the right way forward. “This book is written in a moment of provisionality,” he says, “and it examines the stories we tell ourselves, the scripts we bring to the unscripted, the fables that help to create our futures.” And here’s the point: We’re talking about people even when we’re talking about embryos. “Given biotech that can select and shape who we are, we need to imagine, as broadly as possible, what it means to belong.”

We may know that someone with Down syndrome is a person, but we’re now in a position to ensure that no more such persons are ever born. Should we? It’s a strange and challenging place to be, but here we are. Prenatal testing “drives the way we think and talk about people with Down syndrome: away from a discussion of citizens with rights and toward a discussion of possibilities, potentialities, and risks,” Estreich says. “They occupy a kind of limbo of human value. They are discussed—often inaccurately—in terms of their effect on others, rather than in terms of their opportunities and hopes.” To him, it’s a question of dignity: “For many people with disabilities, the assumptions that their lives are less valuable, or defined by suffering, are assaults on dignity as palpable as any physical fact.”

UNESCO Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights

The General Conference,

. . . Recognizing that research on the human genome and the resulting applications open up vast prospects for progress in improving the health of individuals and of humankind as a whole, but emphasizing that such research should fully respect human dignity, freedom and human rights, as well as the prohibition of all forms of discrimination based on genetic characteristics,

Proclaims the principles that follow and adopts the present Declaration.

A. Human dignity and the human genome

Article 1

The human genome underlies the fundamental unity of all members of the human family, as well as the recognition of their inherent dignity and diversity. In a symbolic sense, it is the heritage of humanity.

Article 2

(a) Everyone has a right to respect for their dignity and for their rights regardless of their genetic characteristics.

(b) That dignity makes it imperative not to reduce individuals to their genetic characteristics and to respect their uniqueness and diversity.

Article 3

The human genome, which by its nature evolves, is subject to mutations. It contains potentialities that are expressed differently according to each individual’s natural and social environment, including the individual’s state of health, living conditions, nutrition and education.

Article 4

The human genome in its natural state shall not give rise to financial gains. . . .

Estreich’s point is not limited to Down syndrome. Thanks to IVF and PGT, any trait could be substituted. In the context of biotechnology, the disabled are seen as “outcomes to avoid,” he concludes. “Their identities are occluded by diagnosis or stereotype, their interiority goes unacknowledged and unremarked, their emotions are simplified by design, and they are rarely consulted.” Yet paradoxically, Estreich continues, they are essential. “As a rhetorical device, disability offers the rationale for the technology’s development and use: that is, a central promise of the technology is that disability will be repaired or prevented.”

The Next 40 Years

Bioethicist Leon Kass foretold, at the outset of this IVF era, that the miracle of life would give way to our imagination and our desire to tinker. “With in vitro fertilization,” he said, “the human embryo emerges for the first time from the natural darkness and privacy of its own mother’s womb, where it is hidden away in mystery, into the bright light and utter publicity of the scientist’s laboratory, where it will be treated with unswerving rationality, before the clever and shameless eye of the mind and beneath the obedient and equally clever touch of the hand.”

How will we decide to move forward? “How we treat people depends on what we think about them, and what we think is both revealed and influenced by what we say. Which is why the rhetoric attached to biotechnology—the rhetoric of the makers—matters,” argues Estreich.

“As a writer, I think about the future. As a parent, I think about Laura’s future. Lately, that future seems more fragile.”

Time seems to be moving faster as the technologies of assisted reproduction take ever more invasive control of the embryo. Despite the distractions of this hectic world, there are decisions to be made. Too complicated? Maybe we’ll give them over to the machines. As Estreich posits, “perhaps, given the conceptual challenges of parsing the differences between disease and disability and variation, we will let the algorithms do the work for us, seeing as ‘abnormal’ that which we can detect or claim to detect.”

That would be the scariest of options. As with all technologies, we need to consider the consequences in a hands-on way. Estreich uses The Amazing Spider Man (2012) to bring his point home. The movie revolves around a scientist’s efforts to genetically engineer the regenerative power of reptiles into the human genome so that limbs can be regrown. Sounds good. As one might expect, though, the best-laid plans to harness biology for human benefit go horribly wrong: gene splicing does not work out well. Of course, this is outrageous comic-book science fiction—or not. Hubris simply comes through more blatantly in the movies. And that’s Estreich’s point.

“[The movie’s] plot embodies the law of unintended consequences,” he explains, “the dangers of intermingling profit and research, and . . . a principled decision not to follow up on a discovery.”

The greater lesson, Estreich brings forward, is that if we are not paying attention to what’s happening in the world, we are each complicit in the evil that abounds. “It is not a single evil user, but billions of ordinary consumers, following ordinary desires—driving cars, wanting healthy babies, going to the movies—that actually shape our world.”