The End of Oil?

The precious liquid that has brought great prosperity to the world may be running out. But unless we come to grips with a deeper issue, empty fuel tanks may prove to be the least of our problems.

This very day as you read, the people of the United States alone will consume 20 million barrels of petroleum. At 42 gallons per barrel, the spigot flows at 35 million gallons every hour, and it goes on at that rate not just today but every day. The United States accounts for more than 25 percent of humanity’s daily industrial energy budget, yet it boasts less than 5 percent of the world’s population.

The seemingly never-ending flow of “black gold” not only feeds the petrochemical industry and the manufacture of an abundance of goods and materials—among them plastics, medicines and fertilizers—much of which will be exported to the other 95 percent of humanity, but it also sustains the transportation industry that moves those products.

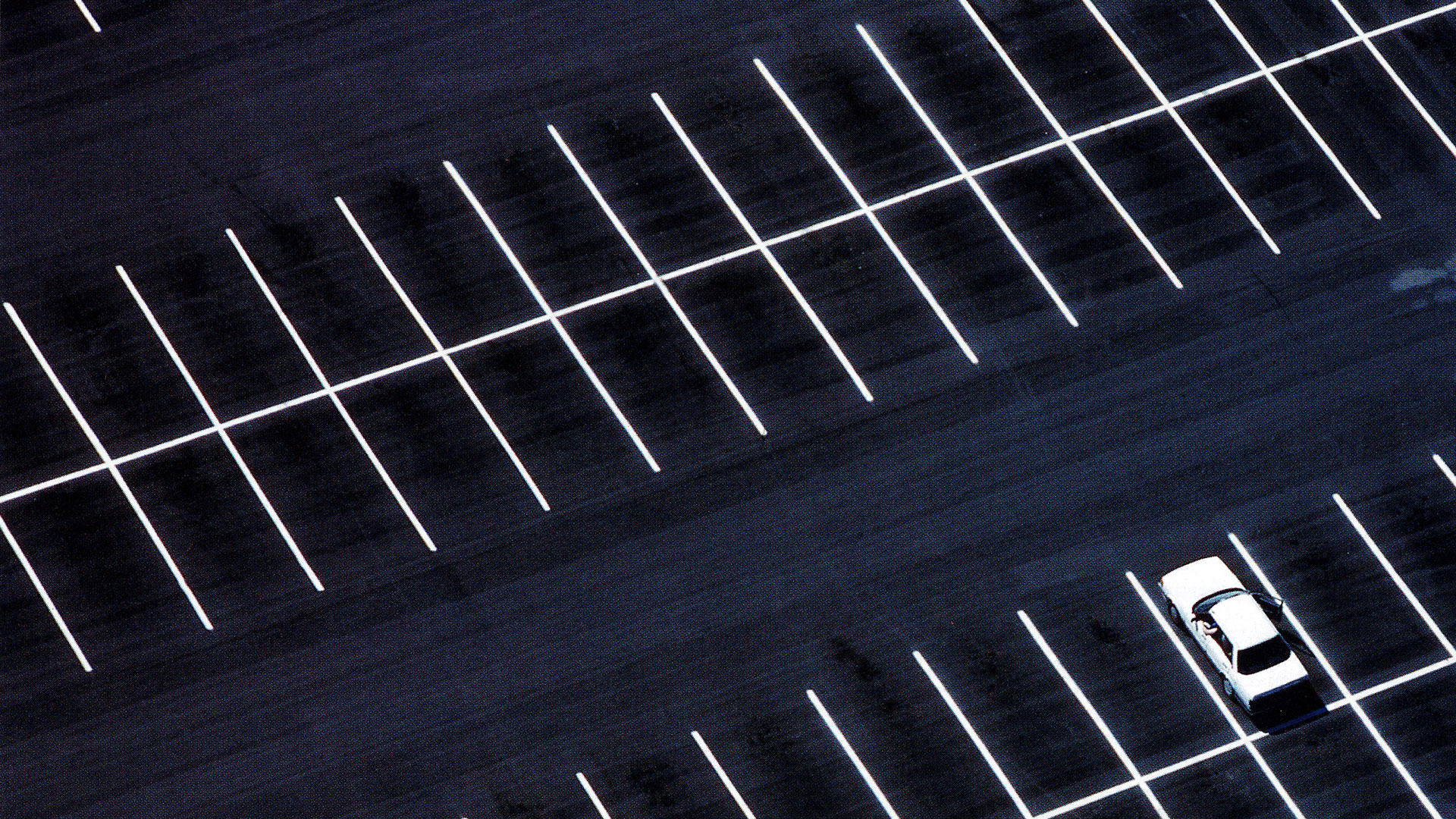

At the individual level, Americans pump millions of gallons of gasoline into their cars each day. Unfortunately, the most mobile population on earth uses many of those gallons for quick jaunts to the ubiquitous shopping mall or for crawling through the so-called rush hours between home and work, some on six-lane highways that bear a greater resemblance to parking lots than to the “autopias” once envisioned. The average American may well burn more fuel waiting in traffic in a day than a Third World family uses to cook its meager meals.

America’s enormous appetite for oil is an immense and easy target for accusations of profligacy: the richest kid in the international neighborhood has an energy disorder. Yet it is a disorder that many on the block envy, desiring as they do the economic might that springs from such consumption. Throughout the world, petroleum is a critical commodity in transportation, commerce and manufacturing. Its supply is an issue of national security, yet no oil-producing Western power operates within its domestic oil supply.

The balance of the world’s nations beyond the United States use a further 55 million barrels of oil each day. A weakened or unstable oil supply would therefore affect the economy of the entire world. Nevertheless, the rate of oil consumption continues to increase. The Energy Information Administration, an arm of the U.S. Department of Energy, forecasts in its “International Energy Outlook 2002” that world energy consumption will increase by a startling 60 percent from 1999 to 2020. As energy requirements grow, petroleum will only increase in importance.

Diminishing Returns

Certainly, few believe that the blessings oil has afforded have come without cost, but most find the benefits to be worth the cost. As a whole, world health, affluence and per capita standard of living have increased over the past 100 years, and these improvements to the human condition have been accomplished on the back of fossil fuel. But concern about the future sustainability of an oil-based world economy continues to rise.

The story of oil as an energy source is surprisingly brief when we consider the fuel’s all-pervasive impact.

The story of oil as an energy source is surprisingly brief when we consider the fuel’s all-pervasive impact. It has changed the world’s lifestyle: there is virtually nothing that does not depend on oil for its manufacture, transport or packaging. Still, it is only a little more than 140 years since Edwin L. Drake’s first extraction of oil deposits in Pennsylvania in 1859. In that time, the world has consumed more than 800 billion barrels of oil at a rate that has grown exponentially. Some sources say we have used more oil in the last 20 years than in the first 120. We have grown far beyond the need for simple lubricants or a replacement for whale oil.

It is now estimated that, when Daimler and Benz engineered the first gasoline-powered automobile engine based on Nikolas Otto’s four-stroke design, there were 2 trillion barrels of oil in the earth. Transportation, and the economies built on the ability to move people and materials, has sent roots deep into those energy stores.

But those reserves, so appropriately termed deposits —like money placed in savings long ago—are not infinite. Even though it is estimated that more than half of the recoverable reserves remain, many authorities are concerned that the graphs indicating world demand and future supply are about to intersect as demand rises and supply falls. Citing the oil troubles of the 1970s as simply baby steps in a march toward a mature crisis, some believe that the United States has painted itself into a corner of scarcity, high prices and the domination of a few international producers.

Chemical Dependence

Today, three fifths of the oil the United States uses is imported. According to President Bush’s National Energy Development Policy (NEDP) Group and its National Energy Policy report, 20 years from now America will gulp down 26 million barrels per day with an even higher proportion coming from nondomestic production.

The report states: “Estimates indicate that over the next 20 years, U.S. oil consumption will increase by 33 percent, natural gas consumption by well over 50 percent, and demand for electricity will rise by 45 percent. If America’s energy production grows at the same rate as it did in the 1990s we will face an ever increasing gap. . . . Extraordinary advances in technology have transformed energy exploration and production. Yet we produce 39 percent less oil today than we did in 1970, leaving us ever more reliant on foreign suppliers. On our present course, America 20 years from now will import nearly two of every three barrels of oil—a condition of increased dependency on foreign powers that do not always have America’s interests at heart” (emphasis added).

“America 20 years from now will import nearly two of every three barrels of oil—a condition of increased dependency on foreign powers that do not always have America’s interests at heart.”

The NEDP, admitting the obvious conclusion that faces the West as a whole, states that this “fundamental imbalance between supply and demand defines our nation’s energy crisis. . . . This imbalance, if allowed to continue, will inevitably undermine our economy, our standard of living, and our national security.”

Petroleum geologists predicted the timing of disproportionate supply and demand more than 40 years ago. In 1956, M. King Hubbert calculated that U.S. oil production would top out in the early 1970s. Similar dire predictions were rightly dismissed when new oil was discovered earlier in the century, but Hubbert’s assessment, denied at the time by most of his peers, was confirmed in 1971, according to Kenneth S. Deffeyes, author of Hubbert’s Peak: The Impending World Oil Shortage.

Deffeyes, a Princeton University emeritus professor of geosciences and former coworker with Hubbert at the Shell Oil research lab in Houston, outlines Hubbert’s methodology: “Hubbert’s 1956 analysis tried out two different educated guesses for the amount of U.S. oil that would eventually be discovered and produced by conventional means. . . . Even the more optimistic estimate, 200 billion barrels, led to a predicted peak of U.S. oil production in the early 1970s. The actual peak year turned out to be 1970.”

Once a nation reaches such a production peak, depicted as the high point of a bell-shaped graph, it will not be able to meet its own demands for oil unless those demands are reduced or an increased supply is imported.

Petroleum geologist Colin J. Campbell notes that all Western countries either have passed or are quickly approaching their own production peaks. He reported his findings in his 1997 book, The Coming Oil Crisis, and in the March 1998 issue of Scientific American.

Volume Control

Although the United States Geological Survey announced larger estimates in 2000, Deffeyes calls these “implausibly large” for both U.S. and world reserves. He suggests that “the 362-billion-barrel estimate . . . is way out in right field. To make the USGS estimate come true, there would have to be new U.S. oil discoveries that add up to the reserves of Kuwait.”

The NEDP report also notes the growing supply-demand gap. There appear to be few places left on earth to find more oil, at least in the great quantities required to meet projected needs. The desire to bring new sites into production, such as the Alaska National Wildlife Reserve, will do little to quench the thirst for increased supplies. (The ANWR’s maximum possible contribution is estimated at around 11 billion barrels—a fraction of the oil needed to cover the U.S. domestic deficit as predicted by current use patterns identified by the NEDP.)

The problem of finite supplies is traced further by Deffeyes. Not only are domestic sources of oil limited, but world reserves are also heading toward a production peak and a certain downhill slide. Following Hubbert, Deffeyes uses current world oil production and oil field discovery data to estimate future production. “The great weakness of Hubbert’s 1956 prediction,” he says, “was his reliance on educated estimates of the eventual total oil production.”

While Hubbert made “educated estimates,” Deffeyes maintains that because more accurate data is available today, a reliable prediction can be made. Using petroleum industry estimates of 1.8 trillion barrels of world oil and a 150-year record of production history, “we find the Gaussian curve that best fits the world production history and has 1.8 trillion barrels under the total curve. That curve reaches its peak production in the year 2003. . . . Although a few exceedingly large estimates have been suggested, a reasonably generous upper guess is 2.1 trillion barrels. [This] gives peak production at the end of the year 2009.”

Consumption as Investment?

Not all adhere to or are disturbed by this scenario of falling supply, increasing demand and the anticipated rising price of fuel. As Bjorn Lomborg, author of The Skeptical Environmentalist, suggests, the real problem may rest in the weak economic motivation to find more reserves. He writes that energy deposits “can seem limited, but if price increases this will increase the incentive to find more deposits and develop better techniques for extracting these deposits. Consequently, the price increase actually increases our total reserves, causing the prices to fall again.”

The use of petroleum and other fuels has led to the creation of great wealth. The availability of energy resources is fundamental to a standard of living that allows a nation to expand its horizons beyond the concerns of daily survival. For all the resources that flow into the Western world, for instance, much also flows out as product, material and monetary aid to the Third World. One could argue about the balance of this equation, but, from Lomborg’s perspective, not using the resource would also be incorrect. Thus, he finds that curtailing the use of energy resources because of their ultimately finite nature is not in humanity’s best interests.

The problem of behaving in an overly conservative fashion, Lomborg argues, is that the loss of economic benefit in the short-term stifles the technological development necessary for long-term growth and a widening of affluence around the globe. He concludes, “The issue is not that we should secure all specific resources for all future generations—for this is indeed impossible—but that we should leave the future generations with knowledge and capital, such that they can obtain a quality of life at least as good as ours, all in all.”

The difficulty lies in replacing short-term economic greed and waste with the long-term goal of creating a better way of life for all.

Building that “knowledge and capital” demands the expenditure of energy. The difficulty, however, lies in replacing short-term economic greed and waste with the long-term goal of creating a better way of life for all. And in our world that is a difficult proposition; the powerful pull of “getting today” what may be gone tomorrow will be difficult to supplant. The insidious nature of greed and of the drive to satisfy one’s own desires becomes potentially even more corrosive as national alliances rise and fall on each nation’s future willingness to buy and sell, to boycott and embargo.

Breaking the Habit

If nations and the world economy have become too dependent on a limited resource, why do we not back away from the brink of future disaster? Writing in The Ecology of Commerce: A Declaration of Sustainability, Paul Hawken notes the paradox of the situation: “It is the nature of the human condition that people will not cut back on their possessions and wants on their own. . . . We are all made anxious by the memories of past economic cycles, experiences that convince us that any type of voluntary reductions are a form of lunacy.” Convenience for self, however temporary, seems always to trump sacrifice.

The oil-based economics of the 20th century have taught us that getting more and growing larger are the only paths to prosperity. The concepts of reduction, simplification and moderation have not been part of the tutorial for success. Our experience is that size matters in the economic game of survival of the fittest; but with largeness come greater demands for sustenance, for energy and for a plethora of other resources. Eventually, those economic creatures that are too large will implode when demand outruns supply or, as others have suggested, the natural systems of the earth itself collapse. Although much of Hawken’s argument focuses on environmental concerns created by what he sees as overly consumptive lifestyles, he recognizes that it is our individual and collective desires that need to change: “We have to be able to imagine a life where having less is truly more satisfying, more interesting, and of course, more secure.”

Crying Wolf or Crying Shame?

Clearly the oil pipeline will not suddenly go dry in the next decade; Deffeyes’ “peak” of predicted world oil production simply sets a marker on what we have known all along: some day the oil will be depleted; the 20th century torrent will become a stream and finally a dribble. However, in the near term the industrial and economic problems may be substantial. Campbell concurs, stating that 2010 will “mark the end of the plateau of world production before long term decline sets in. . . . It will be a period of volatility as recurring oil price surges re-impose recessions and as international tensions grow. . . . While military exploits can certainly change the demand, supply and control of oil, it is worth remembering that discovery and depletion are set respectively by what Nature has to offer and the immutable physics of the reservoirs” (“Oil Depletion—Updated Through 2001”).

Deffeyes echoes the warning: “This much is certain: no initiative put in place starting today can have a substantial effect on the peak production year. No Caspian Sea exploration, no drilling in the South China Sea, no SUV replacements, no renewable energy projects can be brought on at a sufficient rate to avoid a bidding war for the remaining oil.”

One may be optimistic that human intellect will find ways to transfer our reliance from one waning resource to new waxing alternatives. Indeed, if the basis of the dilemma were simply technological, there would be wisdom in a hopeful outlook. The human intellect has achieved great things: spacecraft, planes, trains and automobiles, for example, are tremendous inventions that have given humanity access to this world, to move and to build, to meet each other across the globe as well as above the earth itself. We have used the resource of oil in incredibly innovative ways that have indeed made all of our lives more comfortable. The problem, however, is not of the intellect but of the heart: our motives of selfish desire and gain.

Avoiding Disaster

The limitations of physical resources such as oil will impact us at all levels, from individual lifestyle to international relationships. An oil crisis could change the world overnight, yet because we have weathered such problems before, few of us grasp the need to change the way of thinking that lies at the foundation of this plunge toward trouble. The seemingly constant and reliable world we have created may soon become a place of severe tensions that not only test our physical means but our spiritual condition as well.

The seemingly constant and reliable world we have created may soon become a place of severe tensions.

In the Bible, the supreme time of crisis that will spring from humanity’s wrong motivations is referred to as the “time of the end” or simply “those days.” One of the primary features of that time will be the suddenness of the collapse of the status quo; normal ways of life will quickly unravel. The actual timing will be a surprise.

“For as in the days before the flood, they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day that Noah entered the ark, and did not know until the flood came and took them all away, so also will the coming of the Son of Man be” (Matthew 24:38‚39).

It is a time encompassing a series of events that will culminate in the establishment of the kingdom of God through the literal return of Jesus Christ to rescue humankind from the disaster we have brought upon ourselves. How our ongoing struggle for resources will play into this crisis is unsure and not clearly predictable. It is apparent, however, that the way we live today—both in terms of our rate of resource use and the motivations that drive that use—cannot be sustained indefinitely.

When will this final crisis occur? Jesus answered His disciples, “But of that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, but My Father only” (Matthew 24:36).

While the time remains yet future, the story of oil reveals that we are surely on the road to that destination.