Dark Skies, Bright Hopes

The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

We’ve been searching for signs of extraterrestrial intelligence for more than 60 years, though so far there’s been no contact or evidence of life beyond Earth. Even so, we’ve learned important lessons.

In 1959 physicists Philip Morrison and Giuseppe Cocconi described the strategy in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) by listening for radio signals from space. “We submit,” they proposed in Nature, “. . . that the presence of interstellar signals is entirely consistent with all we now know, and that if signals are present the means of detecting them is now at hand. Few will deny the profound importance, practical and philosophical, which the detection of interstellar communications would have.”

At about the same time Frank Drake, using the radio telescope in Green Bank, West Virginia, began the first search for what he hoped would be ubiquitous signals. He called his work Project Ozma, named for the fictional Queen of Oz (Oz being a location “far away, difficult to reach, and populated by strange and exotic beings”).

He would shortly propose the Drake Equation as a means of quantifying the likelihood of contact with other technological civilizations. Drake (1930–2022) was a radio astronomer, but his desire to make contact reached beyond scientific interest alone. Answering the question “Are we alone?” was fundamental, but both he and others hoped the message would reveal more, and that contact would help humanity chart a better course. If “somebody” out there could do it, so could we.

“Interstellar contact would undoubtedly enrich our civilization with scientific and technical information,” Drake wrote. Also, because the transmissions would have required millennia to traverse space, he surmised that “it is extremely likely that any civilization we detect would be more advanced than ours. Thus it would provide us with a glimpse of what our own future could be. From this we might learn the best course of action in planning the development of our own civilization. . . . We may discover that evolution inevitably leads to a single preferred mode of life. If this be so, let us know it now.”

Clearly there was and still is much more than science riding on this hoped-for encounter. In some ways the search has an almost theological edge to it. Might extraterrestrials, in some godlike sense, have knowledge that could inform our own survival?

Photo by Albert Antony on Unsplash

Moses came to attention when God, in the form of a burning bush, instructed him on his next steps. Is that the kind of intervention we’re looking for in our search for extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI)? It seems so—something startling, literally otherworldly. For the most part we ignore the persistent calls to pursue peace, to love others as we love ourselves, and to recognize that the planetary systems that make our world habitable are suffering at our hand. Although we know a better way—how to love and care for people and planet is not secret information—we don’t seem to have the ability or intention to apply what we know to do. Futurist Allen Tough (1936–2012) put it this way: “We want knowledge for positive and constructive purposes: to help our understanding, to build a better world for future generations, and to enhance our sense of meaning and purpose in the universe.”

We have the brain but not the heart for it. Why is that? Do we expect ETI to provide the leverage to make us choose the better way?

It is this mystical nature of the potential message that continues to inspire the search, even to expand the listening enterprise. Writing in Is Anyone Out There? (1992), Drake never stopped watering that seed of hope. “I find nothing more tantalizing than the thought that radio messages from alien civilizations in space are passing through our offices and homes, right now, like a whisper we can’t quite hear.”

“Perhaps finding actual alien intelligence from another star will guide us to a better future by bringing a messianic message of peace and prosperity to Earth.”

As physicist Morrison later said in an interview, if and when we receive a message, “you’ll have all the deciphering people and all the philologists in the world working on it, studying it like cuneiform.” But the key thing about this information would be that it wasn’t coming from the past; it would be from the future!

“Archaeology of the future is what it should be called,” Morrison continued, “. . . the study of what we’re going to become, what we have a chance to become.” The message could provide “a missing element in our understanding of the universe which tells us what our future is like, and what our place in the universe is.” He concluded, however, “If there’s nobody else out there, that’s also quite important to know.”

A Firmament of Lights or Just One Light?

Astrophysicist Eric Chaisson uses an elegant analogy to illustrate the search for other life in our galaxy: “I have always imagined the SETI search parameter space to resemble a vast chandelier containing some billion light bulbs, each representing a star with a habitable planet orbiting it in the Milky Way Galaxy.”

Chaisson’s model is quite conservative—the “chandelier” of the Milky Way may actually consist of more than 100 billion stars—but his imagery is nevertheless intriguing. The idea is that a lit bulb on this great lamp represents a civilization such as ours: technologically savvy and sending information out across space. For our part, we’ve been leaking radio signals into space for about a century; our first intentional signals were broadcast in 1962.

Besides signals going out at the speed of light, we have also sent slower messages. More akin to notes in a bottle, they’re meant to help other intelligent beings in the galaxy get to know us. Gold plaques showing our male and female silhouettes and a celestial locator for Earth were attached to the unmanned Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft. A disc offering recordings (and, smartly, directions for playback) of Earth sounds as well as greetings in more than 50 languages was placed on the Voyager 1 and 2 probes that traveled to Jupiter, Saturn and beyond. In Korean, for example, they asked, “How are you?” whereas the Arabic message was “Greetings to our friends in the stars. We wish that we will meet you someday.” But don’t hold your breath for a response. Although these were launched in the 1970s, it will be millions of years before they reach another solar system in their paths.

It is the distances between stars that make the likelihood of actually meeting up with extraterrestrials extremely remote; space travel is just too slow. This might be leapfrogged in the movies, but real physics still says no. However, if another technological civilization was out there within 100 light years (the distance our emissions have traveled so far at 186,000 miles per second), it might have already detected our messages. NASA estimates that there are at least 1,000 stars with possible solar systems of exoplanets within that 100-light-year radius.

But there remains another problem: How many “lights” are turned on in the Milky Way in the first place? “Conceivably,” Chaisson writes, “over the history of our galaxy, virtually all the bulbs in this extraordinary light fixture eventually illuminate . . . —but perhaps only a few light up at any given time. That is, such a chandelier might never fully shine brilliantly since only a few bulbs simultaneously brighten—maybe only one (or none) illumes at any moment.”

“Behind the word ‘intelligence’ in SETI is a small but persistent worry that perhaps intelligent civilizations are not intelligent enough—that is, not intelligent enough to avoid destroying themselves.”

And that’s the bigger problem. Maybe there’s nothing to hear. This could be bad news for us. If life inevitably evolves toward technological intelligence, as Chaisson believes, then where is everybody? Does technology lead to self-destruction? If so, can we get off that path on our own? Chaisson asks, “Might the null ‘signal’ contain a ‘message’ that our civilization needs to learn to cope with global problems that could harm, reverse, or even extinguish life [turn off our bulb] on Earth?”

Radio Silence

We’ve been listening for evidence of ETI for more than 60 years now. While searchers remain optimistic, the results have not been what they expected. Just a “thundering silence” is how Nathalie Cabrol describes it. Cabrol is the director of the Carl Sagan Center at the SETI Institute. She is also the author of The Secret Life of the Universe: An Astrobiologist’s Search for the Origins and Frontiers of Life (2023).

In addition to just listening, we have expanded our search to looking for more habitable planets. Cabrol notes that understanding the conditions of other Earthlike planets could help us better understand our own planet. The search “for life on other planetary worlds uniquely opens our minds to the critical importance of maintaining the balance between life and environment in order to understand how habitability was lost, or never was, in so many cases.” This, she adds, “provides us with critical data to identify tipping points that cannot be crossed here on Earth.”

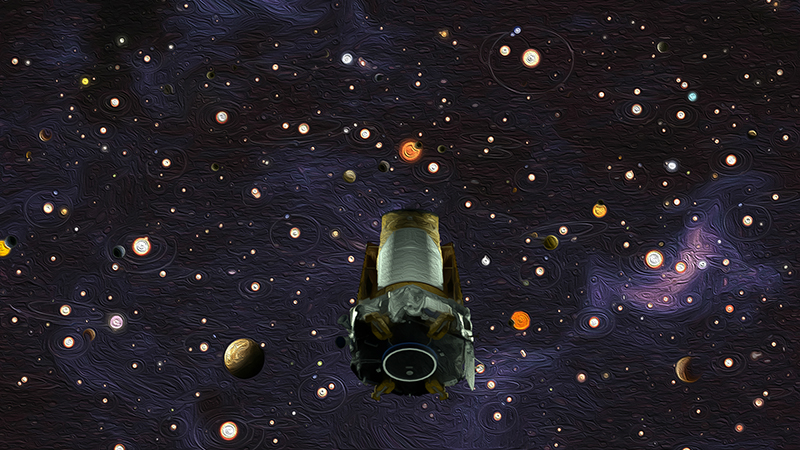

This illustration by NASA represents the legacy of their Kepler space telescope. After nine years in deep space collecting data that revealed our night sky to be filled with billions of hidden planets—more planets even than stars—in 2018 the telescope ran out of fuel needed for further science operations.

NASA/Ames Research Center/W. Stenzel/D. Rutter

Today, almost 5,800 exoplanets have been discovered; most are gas giants like Jupiter or Saturn, but more than 200 are rocky and similar to Earth. As for habitability, Lisa Kaltenegger, director of the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University, notes, “For thousands of years, humans have scanned the heavens and wondered if we are alone in the cosmos. . . . For the very first time, we have the technology to investigate.”

We’ve barely begun to search the Milky Way, yet the universe contains many more galaxies. What about intelligent life beyond our galaxy? A 2024 study using the Murchison Widefield Array of radio telescopes in Australia observed 1,300 other galaxies. The search for “technosignatures” (signals that give evidence of intelligent origin) found nothing. “No such signals were detected,” they concluded.

Tough, in When SETI Succeeds: The Impact of High-Information Contact, reflected the optimistic view of finding ETI. “SETI has not yet succeeded in detecting any repeatable evidence,” he admitted. “But the range of strategies and the intensity of the efforts are growing rapidly, making success all the more likely in the next few decades. More than one strategy may succeed, of course, so that by the year 3000 we may well be engaged in dialogue with several different civilizations (or other forms of intelligence) that originated in various parts of our Milky Way galaxy.”

The existential question that remains is whether or not we will make it to the year 3000.

At a SETI conference, writes astrophysicist Chaisson, “I trotted out my favorite chandelier analogy and was surprised to hear myself saying that the evident silence could well be telling us that it’s time to get our own planetary house in order.”

“Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.”

Chaisson’s point is well-taken; maybe there is no one out there to come to our rescue. “More than five decades of scanning the skies for [extraterrestrial intelligence] ought to be sufficient to infer something about the prevalence of smart, long-lived aliens. . . . While remaining a staunch SETI supporter, I nonetheless surmise that, at any one time, there are likely very few ‘needles in the cosmic haystack.’”

“In short,” Chaisson concludes, “the negative findings thus far for other intelligent life forms might well be alerting us to get our own worldly act together and thereby enhance society’s technological longevity as much as possible—to maximize the ‘L’ factor [civilization longevity] at the end of the famous Drake equation.

“Could the eerie silence from alien worlds actually help to improve this world?”

This is the challenge of our situation. Can we accept the conclusion of our aloneness and embrace that our responsibility now is to take action to alleviate the existential and social problems we’ve created? In an interview with Vision, Diana Pasulka, professor of religious studies at the University of North Carolina–Wilmington and author of American Cosmic (2019) and Encounters (2023), echoed this down-here-right-now conclusion: “Even if aliens exist, let’s get down to us—humans here on earth. We still have to solve our problems; we still have to try to be nice to each other and enact the Golden Rule. These are still the obligations that we have. And there’s probably no scenario, even if aliens existed, where I would believe that they were our saviors.”

Keeping Our Light On

We are here now riding atop a unique and precious oasis, a spaceship Earth that is and will likely be our only home for a long, long time. The ancient wisdom directing us to be good stewards and to care for others as brothers and sisters is increasingly relevant. It isn’t rocket science to understand that the growing social friction among the 8 billion of us, as well as our increasing pressure on the natural environment that sustains all life, will not turn out well unless we make some serious changes. The SETI enterprise, especially after 60 years of silence, really points us back to ourselves as the parties who need to find answers to our problems. We don’t need to find evidence of life or habitable planets out there to intuitively recognize that our life on this little planet is reaching a critical stage.

SETI Institute chair emeritus Jill Tarter notes the greatest lesson we can collectively learn and apply right now. “We’ve seen what happens when we divide an already small planet into smaller islands,” she says in a 2009 TED talk. We need to recognize, instead, that “we actually all belong to only one tribe, to Earthlings. And SETI is a mirror—a mirror that can show us ourselves from an extraordinary perspective, and can help to trivialize the differences among us. If SETI does nothing but change the perspective of humans on this planet, then it will be one of the most profound endeavors in history.”