Inside the Middle East

Events in the Middle East continue to feature in world news as they have for more than a century. Like iron filings in a child’s first magnetic puzzle, they draw in nations from all directions. None, it seems, can resist getting embroiled in what has been called “the cockpit of national identities and perpetual conflict.” Is it possible for the peoples of this region to be reconciled? Can cooperation and lasting peace be achieved?

On almost any given day, the world’s attention is directed to the tumultuous Middle East. This area of the world continues to be a hotbed of strife and tension. The region is home to many complex issues.

Often the focus is narrowed to Israel and Palestine. Now it’s John Kerry’s turn to attempt an American-brokered “just and viable peace.” In the carefully scripted language of diplomacy, according to this secretary of state, all issues are “on the table for negotiation. And they are on the table with one simple goal: a view to ending the conflict.”

Like so many problems in the region, the Israeli/Palestinian impasse has some of its roots in World War I. A hundred years ago, as the opening shots of that devastating war were fired, the stage was set for European and American involvement. With all the ups and downs of a century of bloodshed, broken promises, and meaningless loss of life, it’s the ordinary people of the Middle East who have suffered most.

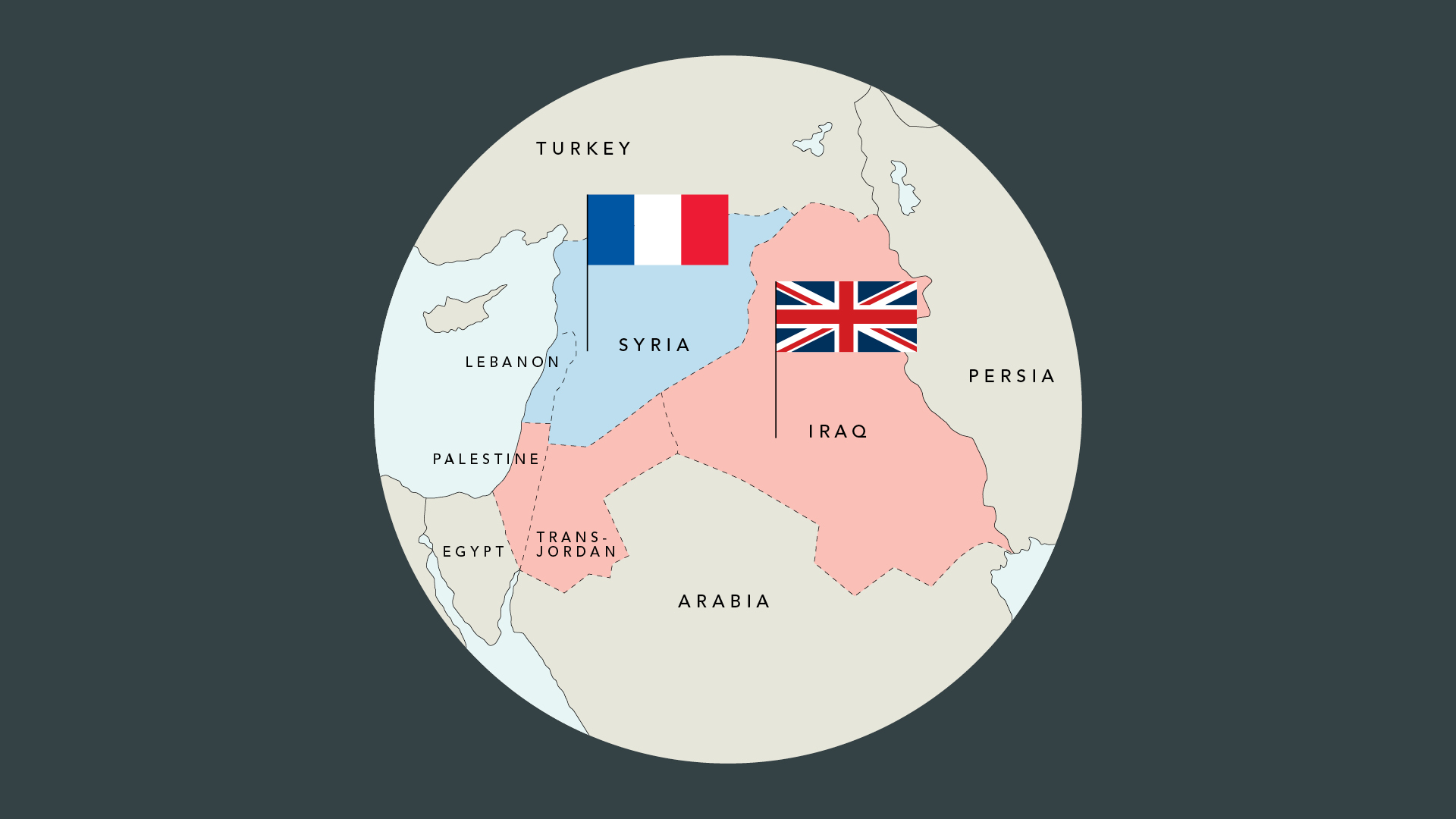

With World War I under way, Allied forces, led by Great Britain and France, were anticipating victory over the Central Powers. France and Britain decided they should divide the spoils of the soon-to-be defeated Ottoman Empire of the Turks, and they signed an agreement which had the potential of redrawing the map of the Middle East. But they kept it secret from the Sharif of Mecca, to whom the British had already promised an independent Arab state, in return for his help in defeating the Turks.

In their efforts to control land and the vast untapped supply of oil, the Allies played the ends against the middle.

The promise of an independent Arab state was also compromised by the British government’s announcement of a sympathetic arrangement with the Jewish Zionists in Britain. One year prior to the end of the war, the foreign secretary sent a short but very significant letter to Lord Rothschild, leader of the British Jewish community.

Known as the Balfour Declaration, it declared the British government would support the establishment of “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. It also stated that in return for such support nothing should be done to “prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.”

This document, perhaps intentionally ambiguous, has been the source of much of the acrimony between the Palestinians and Israelis and more broadly between Arabs and Jews. It lent support to political Zionism, central to the eventual establishment of the State of Israel.

Not long after the end of the war, the victorious Allied powers hastily convened to formalize the new contours of the Middle East. They met on the Italian Riviera in the city of San Remo, where they would divide the territories of the former Ottoman Empire.

France would have mandatory control over Syria and Lebanon; Britain over Palestine and Mesopotamia. The spoils of war were significant. The actual and potential oil resources of the area, along with railways and pipelines, would be exploited and protected by the mandatory powers. For Britain, the Suez Canal was of strategic importance because of her imperial possessions in the east, as was control of Palestine, adjacent to Egypt.

Often referred to as “the war to end all wars,” the events of World War I have cast a long shadow over the past hundred years in the Middle East. According to a recent British foreign secretary, Jack Straw, “a lot of the problems we are having to deal with now . . . are a consequence of our colonial past. . . . The Balfour declaration and the contradictory assurances which were being given. . . . [It’s] an interesting history for us, but not an honorable one.”

It seems that too often it’s the attempts at peace that end all peace. In the Middle East, the turmoil continues. Is there a solution beyond the endless efforts at “just and viable peace”? True peace can come only from outside of ourselves. We humans simply can’t change of ourselves to the degree necessary to end all war. Two thousand years ago, the apostle Peter told an occupying Roman centurion that the peace he represented was available to all who fear God and do what is right. He said that “God shows no partiality” and that this was “the word that [God] sent to Israel, preaching good news of peace through Jesus Christ [the Prince of Peace]” (Acts 10:34–36).

We can certainly do no better than follow that advice as the way to peace.