The Ultimate Commodity

A renowned author and social activist talks about biotechnology, the new economy and the “commodifying” of life.

Not everyone wants to hear what Jeremy Rifkin has to say: inherent in his message is a challenge that few seem prepared to take on. In this interview, Vision publisher David Hulme explores some of the difficult issues that Rifkin has been raising.

DH You’ve written a trilogy: The End of Work, The Biotech Century and The Age of Access. Can you summarize the major factors driving the changes that you talk about in these books?

JR The common thread is that we’re undergoing a tremendous transformation in the nature of commerce. New trends in science and technology are now being introduced on a broad scale in the commercial arena, and they will dramatically affect our way of life.

The first book deals with the shift from mass to elite work forces as we change the nature of work. The second deals with the change in our resource base from fossil fuels, metals and minerals to genes and the biological revolution. And the third is on the shift in the structure of commerce as we move from a market economy to a network-based economy, and from property rights to access rights.

DH You have previously used the phrase “the sacrality of nature.” Is sacrality, or sacredness, background to any of these issues now?

JR Well, yes, in the sense that we’ve inherited a unique legacy. The most important part of this whole experiment is the life pulse. That is the ground of the sacred, and it has been from the beginning of history until recently. Now, with the introduction of these powerful new biological tools and the biotech revolution, we are beginning to ask once again, What is the nature of life? Does it have intrinsic value, or simply utility value? How we approach the age of biology will largely depend on whether we start with the understanding that life first has intrinsic value or that it has utility value. That will determine to a large extent how we use this science—how we apply it in the marketplace and in the social arena in the next two centuries.

I’ve been arguing, especially in The Biotech Century, that there’s a hard path and a soft path. One is based on playing God, creating a second genesis, and being an architect of a commercial eugenics period in history. The other is based on being a steward and a caretaker of the existing creation and using the science to better integrate a relationship with the rest of nature.

I don’t think the issue here is the science itself. It’s very valuable to learn about genes—as long as it’s done in a nonreductionist fashion, and we understand that the genes are not all-powerful and that they are only part of the picture of life. The issue here is how to apply the science in our day-to-day lives—in the commercial arena, in our personal lives, in our culture, in our society and body politic. Right now the only agenda out there is the hard-path agenda of a lot of the life-science companies—which is really an engineering agenda that leads to a commercial eugenics civilization in the final analysis.

I am arguing for a soft-path agenda based on using this science—everything from agriculture to medicine—in a way that allows us to be a steward and a caretaker and to better understand the life pulse and how to work with it, rather than reengineering a second genesis in our own image.

DH I suppose it could be argued that God gave humans the intelligence to figure these things out, therefore God has given us the right to do these things.

JR Well, you could argue that God has given us the choice on how to apply the science. We could apply the science in agriculture for genetic foods with all sorts of deleterious environmental, social and economic consequences. Or we could use the same science to create a very efficient market-driven, organic-based approach to food production based on stewarding an integrative relationship between our food and the local ecosystems in which those food crops are introduced.

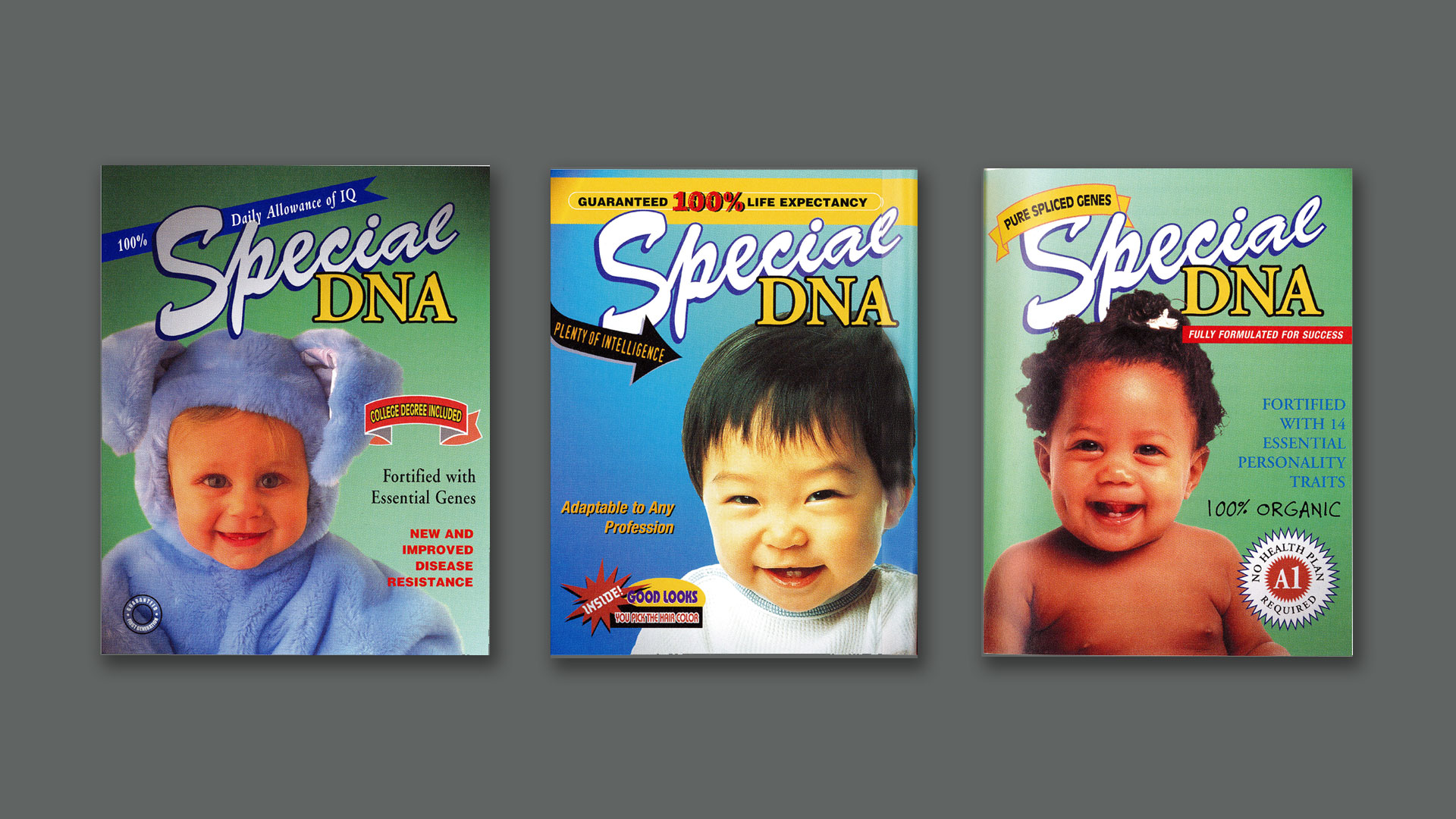

In medicine, the hard path would be to engineer genetic changes in the sperm and the egg—to program our babies so that they become the ultimate shopping experience and we become God. Or we could use the new science to better understand the relationship between genetic predispositions and environmental triggers so we could create a preventive health regime and a very sophisticated market-based approach to wellness.

They are very different agendas, based on very different principles and value systems.

DH The Human Genome Project is obviously progressing, with a first draft having been announced to the world in June.

JR It was heralded as one of the great scientific advances in world history, and they are right. The issue is how to apply this knowledge. For example, do we allow all 100,000 or so genes that make up the human blueprint to become the intellectual property of life-science companies? Or do we find ways to use this new information and knowledge so that it’s more equitably shared as a legacy and a common responsibility of the human race to steward?

I would argue that there’s no problem with companies having process patents, but not product patents. These genes are not inventions. They are discoveries of nature. They are gifts. The cystic fibrosis gene, or the growth hormone gene, or whatever gene—these were not invented in the laboratory. They were simply discovered.

“These genes are not inventions, they are discoveries of nature, they are gifts.”

Our patent laws are clear that discoveries of nature are not patentable. We didn’t allow chemists to patent the chemical elements, like helium, oxygen and aluminum. We did allow them to get process patents on the process they used to isolate these chemicals, but we certainly wouldn’t allow them to claim uranium, helium and oxygen as inventions. That would have been absurd.

The genes are analogous. So I would argue that the soft pathway here is to develop a Great Treaty, signed by all countries in the world, to keep the genetic commons—our biological legacy—as a shared trust to be administered on behalf of future generations and our fellow creatures by the governments of the world, as we did with Antarctica.

If the gene pool is allowed to become the property of governments or companies, I am absolutely convinced we are going to see gene wars in the 21st century, just as we had wars over rare metals in the mercantilist era and over oil in the industrial era. So I think the right thing to do here is to serve as a steward, to keep the gene pool open as a commons, to see it as a shared trust.

I’ll add one more thing to that. I think there’s a very serious philosophical question here. What all parents need to ask is whether their children will be well served if they grow up in a world where they think of life—the genes, the chromosomes, the cells, the organs, the tissues—as inventions. Parents teach their children when they are very little that life first has intrinsic value—that it’s a gift. It’s to be respected. It’s to be honored. When children are a little older, their parents introduce them to the fact that life sometimes has utility value, and we occasionally have to expropriate it.

But I don’t know of any parents who start off teaching their kids that life is simply an invention. If children grow up in a world where they think of life as intellectual property—as information that can be owned, as inventions—it seems to me it drives the very notion of intrinsic value out of the human algebra, and then our children have no reference point in which to even understand what intrinsic value is any longer.

So I think that beside the economic and environmental issues, there’s a much deeper philosophical issue of whether life is a gift or a human invention.

DH What do all these economic developments and the shift to a global-access economy mean for the sovereignty of the nation-state?

JR Well, I think everything is going to be rethought. Beyond the discussion of e-commerce, the Internet and cyberspace, these technologies are introducing a new way of doing business. We are moving from markets to networks, and when we do, it changes our way of life—the social contract, the concept of the nation-state and its role and mission—as dramatically as did the shift from a mercantilist economy to a market economy 300 years ago. So in a sense, The Age of Access is an attempt to lay out the anthropological landscape of this new commercial era, where we move from markets to networks, from geography to cyberspace, from property rights to access rights, and from industrial to cultural production. All of these fundamentally change the way business operates, and with that, it will bring new concepts about the social contract and force us to rethink what government is and what it is supposed to do.

DH Capitalism can be quite a ruthless, rapacious system, exploiting every new opportunity. Do you see the need for a social conscience—some underlying set of values, perhaps—to undergird capitalism and curb its excesses? If so, what do you feel the basis of such values should be?

JR Well, those values always come from the culture, because culture is the primordial sector and the commercial arena is a secondary, derivative sector, as is government. People first establish culture and shared values, and after they create social capital, then they create market capital and form governments.

Culture is where the intrinsic values lie. It’s where faith and theology reside. It’s where our social relations are, our shared metaphors, our intimacy, our sense of purpose. And so we have to approach the new commercial opportunities and challenges by making sure that our cultural resources are enriched and are at the forefront of any discussion. In a purely commercial discussion, the question becomes “how to” rather than “should we?” “Should we?” questions always reside in the culture. “How to” questions are utilitarian and always reside in the marketplace.

DH What do all these developments mean for the future of human conflict and war?

JR Well, it’s not going away. There are some interesting upsides and downsides as we move from a regime based on property relations and market exchanges to one based on access relationships and embeddedness in networks.

We are redefining freedom as we move from market-based economies to network-based economies. In a market economy, freedom is based on the idea of autonomy, and to be autonomous one needs to be propertied. The role of government is to protect freedom by protecting the exclusivity you hold over property. So you can be autonomous and have choices, not be beholden or dependent.

In networks, however, autonomy is death. The dot-com generation want property, but more importantly they want to be connected. They want relationships. They want embeddedness in vast networks of engagement. So for them, freedom is more access to the inclusivity—being involved in relationships—rather than autonomy and exclusivity as it was in our generation, which was so bound to a market-based economy.

DH You’ve talked about greater cooperation, trust and teamwork. What about selfishness, greed and exploitation? Are they diminishing in this type of economy?

JR No, it’s taking on an even more profound form. I have a chapter in The Age of Access on the new monopoly over ideas. If anything, the new power is much more pervasive. If you look at just the development of business concept franchises in the last 20 years, you see the overwhelming power that can be exercised in these vast commercial networks, where property is no longer exchanged in markets but is held on to by the producers so that you and I just access them.

I’ll give you an example. When Monsanto provides seeds to a farmer, there’s no exchange of the seed. There’s no seller, there’s no buyer, so there’s no market. Instead, Monsanto enters into a license agreement with the farmer: the farmer accesses the intellectual property in the seed and can use that information and grow it out for one season, but the new seeds at harvest don’t belong to the farmer, because the property was never exchanged. In this new era of networks, property still exists, but it’s kept in the hands of the producers, and you and I access it in the form of 24-7 relationships. So there’s a greater hold over the stuff of life. That’s a devastating form of control.

“In this new era of networks, property still exists, but it’s kept in the hands of the producers, and you and I access it in the form of 24-7 relationships.”

But you see it in more subtle ways, too. Look at Ford Motor Company. They’d rather never sell another car again. In the United States and Canada, one out of every three cars is still owned by the manufacturer. If they sell you a car in a market, their relationship with you is short-lived, and their control over you is short-lived. If they put you into a lease, where you are accessing the experience of driving rather than buying the vehicle, you become part of the driving experience and you pay for that experience 24-7 for two years. You become part of their network, and you’re beholden to them. That’s the difference between a market and a network.

But there are some upsides. One of the things I mentioned in the book is that environment may be an upside here. In a market, companies aren’t going to protect the environment because it’s not in the bottom line. But in a network it is the bottom line.

So, for example, if Carrier is selling air conditioners, they will sell you the biggest air conditioner you will buy. And if it uses a lot of energy and depletes the ozone or causes global warming, it’s money in the bank. But now Carrier, like other companies, realizes there’s not as much money to be made in market-based transactions and markets as there is in network relationships. So they are now providing “cool services.” Instead of selling you the air conditioner in a market, they put their air conditioner in your residence or business, and then you access their “cool services.” And so you are paying for the ongoing experience of air conditioning rather than buying an air conditioner in a one-shot transaction.

Now the shoe is on the other foot. Now Carrier wants to use as little energy as they can to provide you with quality air-conditioning services, because the more energy they use, the more money they lose. So they would much rather put in retrofitting, lighting or special storm windows to reduce energy use, because they are now in charge of the service and you are now a client.

So think about it this way: In markets you want to maximize production and the sales volume of the transaction. In networks you want to minimize the production and share the savings or have gain-sharing arrangements. It’s a new commercial beast, and in some select industries the environment could be the winner. The downside is that you wake up one day and everything in your world is commodified!

DH In the new economy of the 21st century, what becomes of important ideas that are viewed as commercially unattractive?

JR Well, I’ll give you the best example: Encyclopaedia Britannica. That was a big form of property when you and I were kids. Now Encyclopaedia Britannica has completely dematerialized into a service. It has moved from being a market-based product to a network-based service. Now you click onto Encyclopaedia Britannica’s website! It’s a total service. It’s no longer a product that’s exchanged. You are part of the Encyclopaedia Britannica network.

The upside is that it’s free, because commercial sponsors are putting their messages on particular sites in the service. So if you want to click onto “Rome,” American Express is probably going to be on that site to sell you a discount vacation. On the other hand, chances are that not too many people are going to click onto “Ancient Sumer.” So I doubt that too many sponsors are going to be on that site.

“What happens to those ideas that may be very important in terms of our intellectual history and who we are as a civilization, but not very important to commerce?”

But what’s going to happen two or three years from now? Will Encyclopaedia Britannica spend as much money researching and updating that site, when there are no clicks on it and no commercial sponsors taking advantage of being on that site? What happens to those ideas that may be very important in terms of our intellectual history and who we are as a civilization, but not very important to commerce?

DH Some people talk about the failure of capitalism. One line of reasoning goes that capitalism is intrinsically amoral. It needs a system of morals to sustain it. Christianity, in the United States anyway, was the guardian of those values. So any failure of capitalism is really a failure of Christian values.

JR Amen! I’d like to see that discussion in the pulpits. No one ever discusses it. You’re the only one who would even raise it with me.

DH Well, society seems to be progressively departing Christian values.

JR That’s because there has been a close relationship since the Reformation—a wrong relationship—suggesting a one-to-one seamless web between the assumptions underlying modern capitalism and those bearing witness to the Kingdom. They’re not tautological. In fact, in many ways they are opposites. One is based on intrinsic value and faith; the other is based on utility value and expediency. They’re very different animals.