The Power and Pitfalls of Moral Outrage

Feelings of moral outrage can be a useful signal alerting us to transgressions or injustices. But when do they cross the line from useful to harmful? And how can we focus this emotion constructively?

Among the many emotions common to the human condition are those we’ve come to call negative: sadness, anger, disgust, and so on. Some of these feelings can be normal responses to adverse situations. Anger, for instance, can be useful for alerting us when a personal value or boundary has been crossed, and it can lead to growth if we channel it in a positive way.

Sometimes we may also feel angry when we’re alerted to a boundary violation that affects someone else. This can happen when the emotion is an altruistic response prompted by feelings of empathy for the other person. But it can also be rooted in something much more personal—a sense that our views of morality and justice are being vicariously threatened.

We know this common human emotion by the term moral outrage.

“Moral outrage is justifiable anger, disgust, or frustration directed toward others who violate ethical values or standards,” write Cynda Hylton Rushton and Lindsay Thompson, professors at Johns Hopkins University. “It surges when our moral identity and integrity have been compromised.”

Just as garden-variety anger alerts us to transgressions against our personal boundaries, so moral outrage alerts us to transgressions against our ethical boundaries. It tells us there’s something we need to address, whether an ethical violation against ourselves or against our neighbor. How we address it, however, can make all the difference between whether we foster growth and understanding or simply fall prey to the dopamine rush that comes with feeling morally superior, thus failing to address it at all or—worse—using it to shame others. It can make the difference between whether our approach leads to a fruitful conversation that produces changes of heart, or a shouting match that pushes increasingly polarized groups to dig in their heels and close their minds to change and growth.

The potential pitfalls of this emotion can be predicted by two aspects of its definition: Moral outrage is justifiable—at least it seems so to us when we’re the ones feeling it. And it’s directed toward others, never ourselves. The potential pitfalls, then? Failing to confirm that it’s justifiable, and failing to be honest about our motivations for expressing it.

“I doubt that any of us can think of a time when we were morally outraged at something we did ourselves. Angry with ourselves? Yes. Distressed, stricken with remorse, overcome with shame or guilt? Yes, to all of them. But morally outraged, filled with righteous wrath? No.”

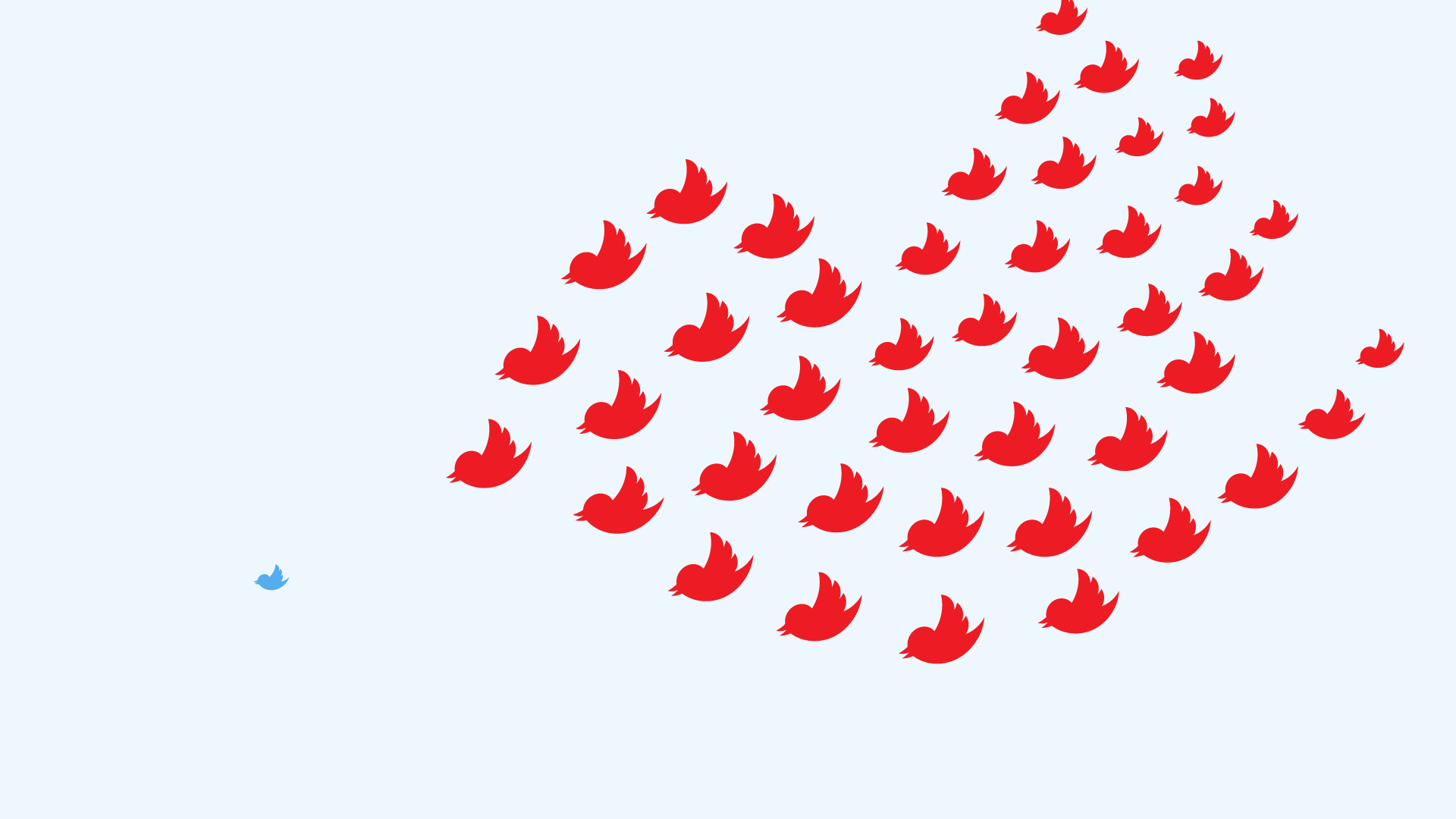

Moral outrage isn’t a new human emotion, although new technologies might suggest people are subject to it more than ever before. It’s more visible, certainly. Since the public stage has gotten bigger, we see more of everyone’s lives than we used to. Anyone’s actions or words can now go viral, and so can the responses to those actions. This gives rise to new terms, such as viral outrage to describe a public outcry against social media posts, and the ensuing comment wars that accomplish nothing beyond allowing people to sidestep any personal responsibility for society’s ills while pointing a finger at someone else.

The terminology may be new, but when we think about how moral outrage played out even before the advent of the Internet, we might consider a number of morally charged scenarios that could be classified as “viral.” Witch hunts come to mind, or mobs whipped up to a frenzy on moral grounds (whether justified or not), sometimes with tragic and distinctly immoral consequences. Whether it goes viral or not, though, moral outrage can divide some and unite others.

We can see evidence of this phenomenon almost anywhere we look online.

Whose Morality?

It’s easy to see how moral outrage can unite people who share the same values and divide those who don’t. But it’s harder to explain how two people can hold the same value and be equally outraged from a moral perspective, yet end up on opposite sides of an issue. Each believes his or her perspective is the only correct view, thereby stifling all constructive dialogue. How is this possible?

Let’s say, for example, that two people both value loyalty. Each may have different ideas of what it should entail, however. What happens when showing loyalty to a corrupt leader means breaking loyalty to the concept of loving your neighbor? Taking a lesson from the Holocaust, we know that people can be convinced to view whole populations as morally corrupt; the resulting outrage can be manipulated to the infinitely more morally corrupt end of annihilating that population.

The takeaway is that to feel moral outrage, we don’t necessarily have to verify that the outrage is justifiable. We only have to think it is. Without an agreed-upon basis for interpreting moral codes, we’re left subject to the vagaries of our cultural context and our willingness to do some basic fact-checking. As it turns out, our perceptions of what is right or wrong in a given situation—and the rewards we get from our social network—can be more important to us in practice than getting to the actual truth of what is right or wrong in that situation. This can leave us vulnerable to those who stand to gain from manipulating moral contagion.

And that leads us to a couple of important definitions. Moral contagion refers to the idea that morally emotional content is likely to be shared through social interactions—which, in our day, happens mostly through online social media. Moralized content is content that’s relevant to contexts beyond our interests as individuals. We see content in moral terms when we see it as relevant to the good of the larger society around us, the culture we’re embedded in, or our personal social network. It’s worth restating that we only have to think the content is accurate or that it has moral implications. Might we be wrong? Perhaps, but because sharing things on social media is so easy, so spontaneous, we often don’t even consider fact-checking our assumptions.

In 2020 a group of researchers from Yale and New York University looked at why and how moral contagion works online. They ask what it is that “makes different types of online content go ‘viral.’” Part of it, they explain, has to do with the simple fact that emotionally arousing content just gets shared more. But it happens more quickly when there’s a moral component attached to it. And it spreads even faster when we share this content among social connections who are like us—people with the same group identification and group-based emotions. Our motivations for spreading it, the researchers argue, may be twofold: Expressing outrage and contempt for out-groups makes us feel good about how our in-group compares. But we also want to feel good about our reputation within our group; it feeds a personal and shared sense of elevation and awe.

“If moral outrage is a fire, is the internet like gasoline? . . . This is an empirical question that behavioural scientists should address, because its answer has ethical and regulatory implications.”

The upshot is that moral contagion happens so easily on social media because 1) moral-emotional content captures our attention, 2) our group-identification motives drive us to share it, and 3) social media is designed to amplify these motivations and drives.

It’s called “social media” for a reason; our connections mostly tend to view the world as we do, which can create an echo chamber for a narrow perspective. Even if we’re connected to some who think differently than we do, these may be obligatory connections. They may be near or distant family, or people we know from school or from clubs—people who aren’t necessarily “chosen” by us (but whom we also don’t feel we can unfriend online). The algorithms soon figure this out through our lack of likes, shares and comments, so we see their posts less often. At the same time, our likes and shares tell the algorithms who and what we do agree with, so they serve up more of the same.

But likes, comments and shares are not only training the algorithms. They’re also training us. And they’re training us to expect and express moral outrage more frequently. This happens not only because we repeat behaviors that are reinforced through positive feedback (and the best marketers know that positive reinforcement is a far more powerful force than punishment), but also because we receive more reinforcement for behaviors that are considered normal among our in-group. These influences are true offline as well as online, of course. But they’re amplified online, where we can more easily organize ourselves into groups that agree with us—and where social media algorithms exploit our predisposition to reinforcement learning.

As the researchers in a 2021 study published in Science Advances put it, “even if platform designers do not intend to amplify moral outrage, design choices aimed at satisfying other goals such as profit maximization via user engagement can indirectly affect moral behavior because outrage-provoking content draws high engagement.” In other words, marketing and advertising goals heavily influence how algorithms are designed. The human tendency to engage with emotionally provoking headlines trains the algorithms and the content developers to feed us more of them, and a vicious cycle ensues. Manipulating outrage makes money—for YouTube channels, for news outlets, for pseudo-news outlets, for anyone who wants our eyes on their product. As long as stoking moral outrage is good for the bottom line, outrage-inducing material will cross our feed in the form of memes, reels, videos and other shareable content. And we will very likely comment on it, like it, share it—and extend its life.

“Every day, new compelling content must be generated. And each day much of that content is outrage, which is inexpensive to produce, dramatic enough to cut through the clutter of alternatives, resonant with our current cultural milieu, and . . . comforting for fans.”

But that’s not the whole story, and the researchers we’ve looked at so far aren’t the only ones studying moral outrage. That’s not how research works. Inroads on any subject are usually made on multiple fronts at once, so the challenge is in pulling all the threads together to get a coherent view of a very complex issue. We’ve seen how susceptible we are to moral outrage (whether it’s based on truth or not) and how social media and content producers can exploit that. Can we conclude, then, that moral outrage is a bad thing?

Upsides Downsides

According to research published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, to ask whether moral outrage is good or bad is to ask the wrong question. “Emotion and reason are not mutually exclusive,” the researchers point out; feeling moral outrage can certainly lead people to express themselves in divisive ways online, but it doesn’t have to. It can also lead to positive outcomes and help influence people to think and behave differently. “Online outrage is not an emotion,” writes Victoria Spring with her colleagues. “It is one possible behavioral response associated with experiencing outrage.” Clearly we have alternatives in how we express outrage. Spring and her team point out that emotions like this one can draw our attention to important cues that help us clarify our values and rationally inform our decisions.

Because it often stems from a deep sense of injustice, moral outrage can spark an equally deep desire to bring about important changes. Human history has demonstrated that moral outrage can be a powerful force for good in shaping society’s view of how to treat others better and in motivating behaviors that help others. Well-placed moral outrage has played a role in raising awareness of human rights violations, injustices, inequality and abuse, and it has often led to change.

But just as often, that change has fallen short for any number of reasons. In some cases, our motivation to restore justice is sincere, but our conversations get derailed. Minor differences can turn into insurmountable obstacles that keep us from identifying common ground that would give us a shared purpose. Or we may get caught up in trading blame, which fuels a cycle of fruitless argument, leading to outrage fatigue and bringing progress to a halt.

Sometimes the problem is our motivations. Are they sincere enough to inspire us to work on change? “While bystanders’ expressions of outrage may represent a genuine desire to restore justice or protect the victimized,” write moral psychology researchers Zachary Rothschild and Lucas Keefer, “recent research suggests that outrage can be self-serving; alleviating guilt and bolstering perceptions of one’s moral character. . . . This raises the possibility that bystander outrage may not necessarily be motivated by concerns with justice per se. So how do we differentiate between expressions of outrage reflecting a genuine concern for justice and those driven by less altruistic concerns about personal moral status?” In other words, how can we tell the difference between righteous and self-righteous outrage?

One clue, they found, lies in the fact that we each have differences in our awareness of injustice as well as our sensitivity to it. Where we lie on these continuums depends on how firmly we value justice as a universal moral principle. People who are more sensitive to the injustice they see are less likely to be motivated by moral superiority or defensiveness when they express outrage, and they’re more likely to work toward change. On the other hand, people who are less sensitive to the injustice they observe tend to express outrage when they’re looking to soothe a sense of personal guilt or to feel morally superior. When one of these two motivations is at the heart, simply expressing outrage against injustice is often enough to make people feel as though they’ve done their fair share and can move on.

Whether motivations are pure or not, one could argue that marshaling the troops to stand against injustice can have only good consequences. Unfortunately, that’s not always the case. Two Stanford University researchers suspected that the idea of “safety in numbers” doesn’t necessarily apply when it comes to expressing moral outrage, so they decided to give the question a closer look. Their findings? Even though we usually admire someone who defends against injustice, we can also turn on the defenders if we feel that the target of the outrage is being overwhelmed. “This is the paradox of viral outrage,” Takuya Sawaoka and Benoît Monin explain. “The exact same individual expression of outrage may appear laudable in isolation but morally suspect when accompanied by a chorus of echoing outrage.” It does make sense. When the punishment doesn’t fit the crime or injustice, the punishment itself becomes an injustice.

“The ubiquity of collective outrage may dilute its persuasiveness and impact, as viral outrage blurs the line between righteous protest and collective bullying.”

Harnessing Outrage

We’ve seen that well-motivated moral outrage can be a force for good in addressing injustice—as long as its underlying moral compass is sound. But what makes a sound moral compass? It would be difficult to come up with a fundamental value sounder than “Love your neighbor as yourself,” provided that your neighbor is defined as “all of humanity.” But the information feeding our outrage isn’t always accurate, and our own biases about every aspect—including who is our neighbor—can easily get in the way of good judgment. So how do we safeguard our thinking? Two keywords can help: reflection and respect.

1) Reflection: When we see a headline, watch a video, or hear an accusation that gets our blood boiling, it’s helpful to reflect on our own motives and blind spots, as well as the motives and blind spots of the content authors. Are my feelings really based on righteous justifications, or could they be better classified as self-righteous? What’s the context of the disturbing information, and can I verify its claims? Are they based on reliable sources? Are there perspectives to consider that the authors were unaware of or perhaps intentionally left out? Is the content meant to make me angry at a specific group of people? Do the authors have anything to gain from promoting controversy? After taking the time to answer all of these questions honestly, if we still feel indignation and are convinced it’s indeed the righteous kind, then we can move on to the second keyword.

2) Respect: Channeling moral outrage constructively often requires having meaningful and respectful conversations about the problem we’re seeing. If we did our homework in the reflection phase, we examined our motivations and verified the truth of the injustice we observed. We must recognize the need for humility and respect when we discuss the injustice with others who may have different perspectives, or who don’t yet recognize its existence. This may mean that our only option is to enact small changes on a personal level. Or we may be in a position to address the problem on a larger scale more publicly, raising awareness of the injustice to encourage others to also make personal changes. Other options might include engaging in a dialogue with those who are able to do more than we can. Whatever avenues are available to us, the goal is to avoid accusations and blame, and instead to look for common ground while acknowledging complementary efforts.

As an important emotional force that has the potential to balance our darker side, feelings of moral outrage won’t go away anytime soon. As long as there is human cruelty, abuse of power, inequality of all kinds, manipulation, hate, greed, careless consumption and corruption, human beings (we hope) will continue to experience moral outrage in response. But how we channel this emotion, how we express it to others, and how we use it to become better people will make all the difference in its value to society.