More, More, More: Contemplating Our Overcrowded Future

Countdown: Our Last, Best Hope for a Future on Earth?

Alan Weisman. 2013. Little, Brown and Company, New York. 528 pages.

Creating Regenerative Cities

Herbert Girardet. 2015. Taylor & Francis Group, Routledge, New York. 216 pages.

The Emergent Agriculture: Farming, Sustainability and the Return of the Local Economy

Gary Kleppel. 2014. New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, British Columbia. 192 pages.

When supplied ample resources, all life forms have the reproductive capacity to grow exponentially, as depicted in the well-known J-curve graph. Absent population growth controls—predators or herbivores, for example—a species may take over an ecosystem. While that species may flourish for a time as it dominates its world, the fact of its biological single-mindedness to eat, breed and eat some more can lead to the collapse of the system that supported it to begin with. No living thing lives in isolation.

The kelp–sea urchin–otter dynamic along North America’s western coast is a classic example of how natural checks and balances operate on populations. The kelp forest is a rich system of interacting kelp-reliant species: no kelp, no forest, no species, no ecosystem. Urchins feed on the base stalk of the kelp; when eaten through, the long strands either drift out to sea or are washed ashore. Otters feed on the urchins and thus keep their population from expanding. Without the otter, urchins are unregulated. They will consume more and more kelp until the forest becomes a sea-bottom clear-cut, a barren ruin. The forest system drifts away piece by piece. To paraphrase Jared Diamond’s remark about Easter Islanders cutting down their last tree (Collapse, 2005), “I wonder what the urchin thinks as the last strand of kelp slowly rises away? Does it know it just destroyed its own livelihood?”

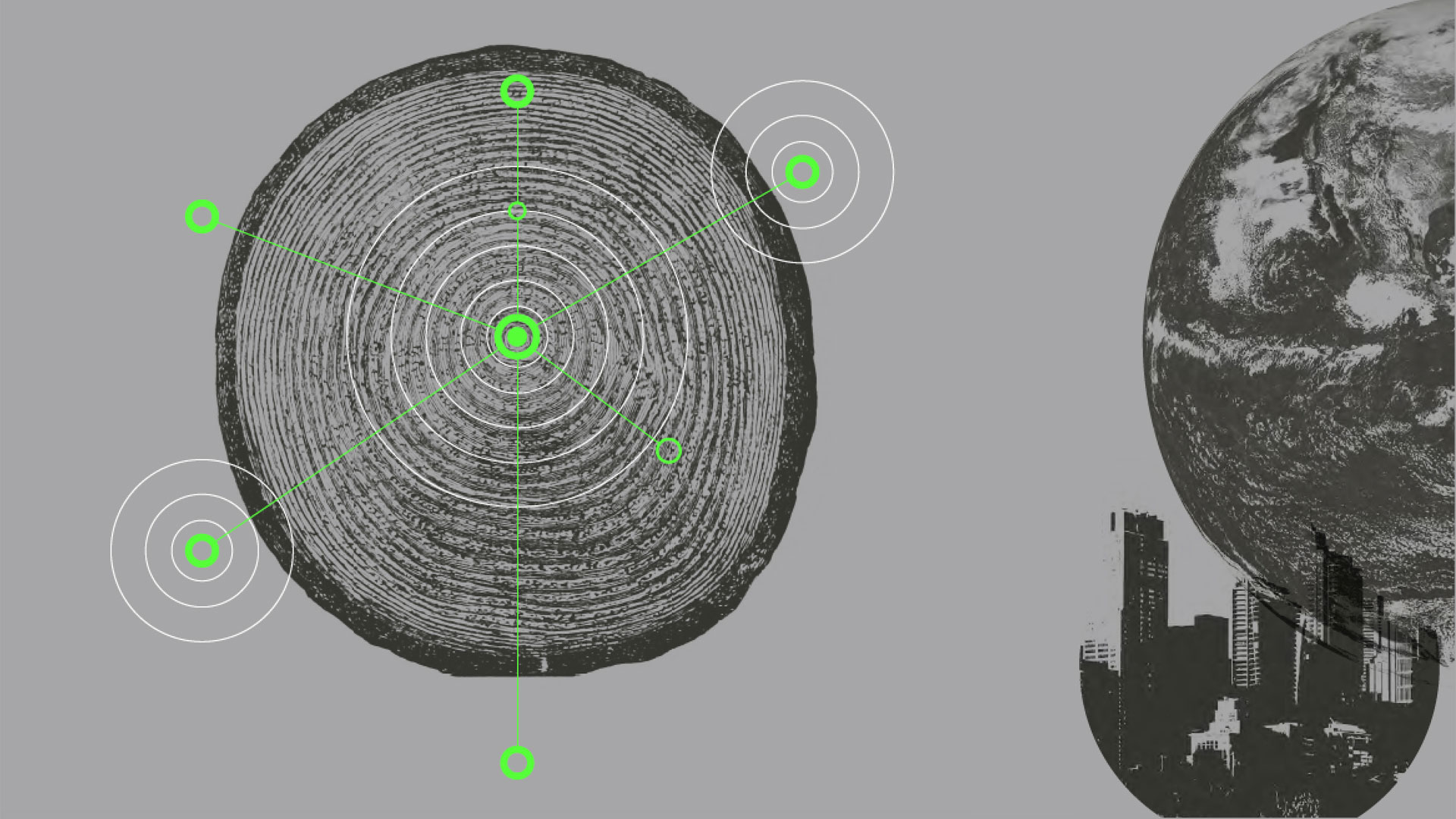

What about our planetary livelihood? Like a blind, oblivious sea urchin, are we also involved in a kind of self-destruction as we grind our way across the earth, unaware that we’re interlocked with the rest of the planet’s natural systems? We have obeyed the instruction in Genesis to “be fruitful and multiply”; in our seemingly endless ability to creatively modify, consume and reorder all manner of living and nonliving materials, our dominion is expansive. One cogent study of several baseline thresholds notes: “The human enterprise has grown so dramatically since the mid-20th century that the relatively stable, 11,700-year long Holocene epoch, the only state of the planet that we know for certain can support contemporary human societies, is now being destabilized” (Will Steffen et al., “Planetary Boundaries,” 2015).

In another study, ecologist Jane Lubchenco lays out our collective responsibility. The conclusions are “inescapable,” she writes. “During the last few decades, humans have emerged as a new force of nature. We are modifying physical, chemical, and biological systems in new ways, at faster rates, and over larger spatial scales than ever recorded on Earth. Humans have unwittingly embarked upon a grand experiment with our planet. The outcome of this experiment is unknown, but has profound implications for all of life on Earth” (“Entering the Century of the Environment,” Science, 1998).

The dilemma is whether or not we can recognize our potentially blighted future before it becomes the present. Are we smarter than a sea urchin?

It’s obvious that the problem of how we will manage our infinite desires in a finite world will be with us for a long time. Three books suggest possible solutions to what might be termed the Big Three human factors pressing on those planetary boundaries: more population, more urban development and more agriculture.

Four Questions

Alan Weisman recalls gazing at a stuffed passenger pigeon displayed in a Minneapolis library/museum when he was a boy. “Even when there were a million left,” he muses, “they were already functionally extinct, because the pattern that doomed their critical habitat and food supply was already set.”

“Do we have the will and foresight to make decisions for the sake of descendants we will never know?”

In Countdown, Weisman wonders if we are on the same path. We may in a sense still be filling the skies; but, he asks, might we “already be the living dead?”

That’s a pretty pointed question, and he frames his book around four more: 1) How many people can our planet hold? 2) Is there an acceptable, nonviolent way to convince people of all cultures, religions, nationalities, tribes and political systems that it’s in their best interest to reduce the number of humans on earth? 3) How much ecosystem is required to maintain human life? 4) How do we design an economy for a shrinking population, then a stable one—i.e., an economy that can prosper without depending on constant growth?

Weisman takes a global trek to explore the idea of population control, and especially the problem posed by Question 2. Yet, even at more than 500 pages, his book offers no sure answers to any of these questions. As a journalist, Weisman is clearly more interested in the discussion than in an empirical answer. It is an interesting travelogue, though many of the stories are overextended and inconclusive. But it is a work that wants to be helpful, to provide food for thought rather than a recipe to be followed.

Weisman sets up the narrative with a verse from Revelation: “This calls for wisdom. If anyone has insight, let him calculate the number of the beast, for it is man’s number” (Revelation 13:18, New International Version). The verse’s context is not population, but Weisman bends it to say that humans are the problem, the beast, and that the only solution is to have fewer of us. Thus the double meaning of the title: we are either on a countdown to disaster as our population overwhelms the global systems that support us, or we must begin to count down the size of the population by actively choosing to have fewer children.

How many is the right number for a country or a planet? Determining this number, or whether it can be determined, is “a saga that has engaged—and enraged—religious authorities, philosophers, and scientists throughout history. It is a saga summed up in a single question: What are we?”

Though Weisman does not plainly answer this question either, it is the ultimate question. He asks further, Are we a “highly evolved” creature, or “divinely imbued”? Either way, he understands that we do not “transcend [physical] rules governing the rest of nature.” The concept of fruitfully multiplying with abandon and without a sense of sustaining one’s family, whether personal or global, is not realistic from a material or a spiritual worldview.

“Let’s define optimum population as the number of humans who can enjoy a standard of living that the majority of us would find acceptable.”

Weisman’s gospel, echoing that of other planned-population advocates, is contraception. Global evidence and anecdote show that women will use birth control when it is available and when the civil situation is stable. Countdown is, in sum, an argument that greater equity between rich and poor, education for women, equal rights, and the promise of a secure future are the factors that promote population control. He also notes that “simple, nontoxic male contraception . . . would far more equitably share responsibility for planning families.”

“The Earth can’t sustain our current numbers,” he writes, “and inevitably, one way or another, those numbers must come down.” His hope is that we will not end up where his previous book, The World Without Us (2008), began.

Inputs and Outputs

Whatever happens in the long or short term, people will need a place to live. And that place is increasingly going to be cities, already home to more than half of all people on earth. “As cities become the predominant human habitat,” writes Herbert Girardet, “urban development needs to undergo a profound paradigm shift.”

Girardet’s Creating Regenerative Cities describes how cities have developed and how they must change if they are to support this urbanizing population. As cofounder of the World Future Council, he has worked as a sustainable development consultant for cities such as London, Vienna, Bristol, Adelaide, Shanghai and Riyadh. With 50 television documentaries and 12 books to his name, his involvement with the subject is long and deep.

One would therefore expect to find concrete strategies and policies in this work. But like Weisman, Girardet often creates more questions than answers. Still, as sustainability becomes more pressing, his ideas will likely gain greater acceptance and applicability.

Urban centers have always been dependent on outside resources, but current and future megacities have an increasingly long reach into the world around. Cities are like living things. Each has a kind of metabolism that must be supplied with nutrients, and its wastes and by-products must be removed. This equilibrium of inputs and outputs will become increasingly hard-pressed as cities swell into larger and larger masses. For example, while Beijing was the only city of 1 million in 1800, it is estimated that by 2025 there will be 600. Today there are over 30 metroplexes with more than 10 million people.

Consider the urban footprint of a large city. Supplying tens of millions of people in a Los Angeles or a London with food, water and other commodities is a huge task. Removing its solid and liquid wastes (as well as its export of manufactured goods) is an engineering marvel. But how these tasks are accomplished must be rethought. Can the local environment support a megacity?

“Large modern cities are dependent systems. Much information now exists about the vast amounts of energy, water, food, timber and the many other raw materials they require. However, so far little is being done to ensure the long-term availability of these existential supplies.”

Girardet outlines the evolution away from Agropolis—the small city surrounded by the gardens, pasture and woodlands that feed it—to the current urbanized and fossil fuel–dependent Petropolis. Ecologically, both models are one-way systems that are ultimately unsustainable; resources flow in and wastes and products flow out in a purely consumptive model. And herein rests the problem: “The feast of energy and resource consumption we are engaged in is an exercise in accelerated entropy—it is up against non-negotiable natural laws and limits.” Eventually this one-way flow will exhaust feed stocks and deplete soils.

Because such linear paths are doomed, “we need to ensure that urban consumption patterns become compatible with the world’s ecosystems.” Girardet argues convincingly that the current trajectory of urbanization is heading toward a crisis—that we need a regenerative model of urban life if Western lifestyles are to be maintained. But they can never be for everyone: “If all the world’s citizens had resource and energy demands as high as those in London, New York, Los Angeles or Berlin, we would need three to four planets.”

City as Ecosystem

The regenerative model Girardet promotes is called Ecopolis: a kind of city-as-ecosystem where the inputs and outputs are reconnected. One could say that it closes the loop on waste; “cradle-to-cradle” is the new reduce-reuse-recycle mantra. Ideally all fossil-fuel inputs are replaced by clean, renewable energy, and food and manufacturing efforts are brought nearer the city they support, using the waste products of the city’s own food and manufacturing consumption as inputs for the continuing production of food and goods.

This relocalization of the city seems credible in theory, but is it so in practice? Are millions of city dwellers simply too many to support locally?

The strongest positive example is one in which Girardet was involved. The city of Adelaide, South Australia (more than a million residents), enacted 31 regenerative strategies in 2004, including incentivizing organic waste composting; “over 30 per cent of electricity produced by wind turbines and solar . . . panels”; “15 per cent reduction of CO2 emissions”; and the creation of “thousands of new green jobs.” While these may be laudable, the magnitude of change is small or discussed in imprecise terms. It is unclear whether these efforts can be scaled up to meet the needs of a larger city. Unfortunately, significant government regulation and withdrawal of support midway through the implementation process limited their long-term effectiveness.

“We all rely on a steady supply of natural resources from across the planet and are often oblivious of the environmental consequences. Yet there is growing evidence that our resource use is gravely damaging the life support systems on whose integrity our cities ultimately depend.”

One key area that will need retooling in Ecopolis is agriculture. Girardet believes that “greater reliance on local supplies reconnects consumers to local producers and can also help to feed the world’s growing numbers of affluent people.” Food miles (the distance food must travel from producer to consumer) will need to be reduced; green belts will need to be redesigned around urban centers; city waste will need to somehow flow back to replenish the land. As Girardet notes, up to now the solution to urban food has been rural development—a one-way ticket from land to mouth. And “since developing countries are increasingly copying Western urban diets and lifestyles, their [farm]land requirements are increasing rapidly.”

Biologist and local farmer Gary Kleppel agrees. In The Emergent Agriculture, Kleppel offers a view of the farm that coincides with Girardet’s localized vision. It’s a journey away from the current industrial agricultural system of distant mega-acreages, mass production and transportation. Although modern agribusiness supplies much of the Western world with consistent and low-priced commodities today, he questions whether it can do so in the long term. According to Kleppel, the kind of farming most of us rely on (based on fossil fuel–based synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides and fuels) is inherently “unsustainable, dangerous, inhumane, dehumanizing, and toxic.” He joins Girardet in suggesting that a sustainable system must be more holistic: the soil, water, air, animals and people being served must all be considered integral and important parts of the food network. Such a system would consider not only the present but future generations as well. The message is that true agriculture must reemerge.

Craftsmanship or Cheapmanship?

Kleppel, professor of biological sciences at the University at Albany, defines sustainability as “the capacity to endure.” The principles embodied in this concept are best described as adhering to the “triple bottom line”: “environmental stewardship, economic viability, and ethical behavior.” He practices such sustainable techniques on a small farm outside Albany, New York, with the local farmer’s market as his outlet.

Small-scale farming and a direct producer-to-consumer relationship is how Kleppel believes integrity can be restored to our food system: “If current trends continue, about two-thirds of the American public will soon have access to locally, ethically, and safely produced food. . . . An array of forces, including increased personal wealth and an explosive growth in the number of locations where sustainably produced food can be conveniently purchased, are combining to bring middle-class consumers into the emergent markets.”

“The emergent agriculture represents an alternative to what is increasingly recognized as an unsustainable industrial system.”

Ultimately this is a book written for that concerned consumer, not the policymaker. “Growing consumer appreciation for agricultural craftsmanship and its contribution to the quality and safety of our food is driving the transformation in agriculture,” he writes. In this sense Kleppel’s discussion of food labeling is most helpful. For discerning consumers seeking to improve their awareness of the issues, this section alone is worth the price of the book.

Kleppel’s is an educational mission. He decries the “reductionist” way of farming, the factory mindset from which most food today is produced. In this pixelated view, each ingredient or product—whether soil, apple, ear of corn, or cow—is merely the sum of its chemical components. This is a dis-integrated and ultimately flawed system, Kleppel argues.

He maintains that producing sustainable food is a craft, not a chemistry equation. For example, soil is not just a kind of inanimate root-holding aggregate. Rather, it “consists of a complex and somewhat mysterious fusion of microbial and geochemical components that together form a living medium.” Focusing on the health of the soil, he says, is the right place to start. The apparent need for synthetic inputs of nitrogen and other chemicals in modern agricultural practice indicates a broken system—a vicious cycle where each new synthetic input further disrupts soil’s holistic nature.

His vision of sustainable agriculture is that it would be done on a smaller, more localized scale and be less reliant on large mechanical devices and on chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides. It would integrate plant and animal production and emphasize crop diversification, which would maintain proper natural biological controls to manage pest and weed problems.

This would obviously compromise the mass-production model now in place but would also affect food prices. Unfortunately the West demands cheap foods, while agribusiness pushes for profits. This combination will be our downfall, according to Kleppel. Free-trade agreements may lower costs (even with increased transportation costs from farm to market), but he counters that “what will be compromised . . . are food quality and safety. The offshore shift in food production will ratchet down overall food security and this, I predict, will be the undoing of the industrial food system.” In other words, pay attention to the origin of the products you purchase. Transparency—the reporting of production practices and point-of-origin—is a helpful if controversial trend in this regard.

The marketplace, however, seems to be driving business in Kleppel’s direction. As Girardet might agree, the “3000-mile Caesar salad” may have run its course. As consumers become more aware of the practices behind the products they consume, they are opting for a more natural, less synthetic diet; one could call it more “green.” He hopes that “the emerging tide of sustainable agriculture may sweep away the old and stale, leaving in its wake a system of food production and consumption that does not deplete resources, degrade ecosystems, abandon ethics, commodify the life support system, or dehumanize the people who produce our food.”

The Price We Pay

As more of us recognize the value of sustainability, we take on a broader view of our relationships with each other, the world we create, and the natural world we all depend on. These writers hope that such a positive synergy will create “something larger”—in Kleppel’s words, “an ethic of environmental stewardship, social justice, and animal husbandry, attributes ignored during the past six decades.”

“I predict that increasing numbers of farmers will abandon industrial food production and commodities-based marketing, preferring the more appreciative, humanizing, and often more lucrative alternatives that are emergent.”

Unlike the sea urchin, we have the capacity to choose our behaviors; we recognize options and consider consequences. Our choices do make a difference, both individually and collectively. But to turn the corner on these problems, that positive ethical synergy must come from somewhere. We are enduring a world of malconstructed cities, mismanaged agriculture and human squalor because we have lost track of the source of right ethics.

Weisman ends Countdown with another reference to the Scriptures—Revelation 11:18 and the special recompense for those who spoil the creation: “The nations raged, but your wrath came, and the time . . . for destroying the destroyers of the earth.”

This prophecy does not suggest God’s dislike for cities, agriculture or population size per se. At the outset humans were told to build families and grow (Genesis 1:28; 9:1); Abraham was promised descendants numbering as the stars of heaven (Genesis 12:1; 15:5). God intended man to use the land, but under His stipulations (Genesis 1:29–30; 9:2–3; Leviticus 11, 25). There will be cities in the prophetic future; agriculture will remain a major enterprise. And if one considers that virtually all who have ever lived will be resurrected to live again on the earth (1 Corinthians 15:22–24; Revelation 20:4–5), then the planet must have the capacity to sustain many billions.

Today we are captives of our wrong ways of living. The good news is that our Creator will rescue us, but not until we have almost exhausted our human resources. There is a price to pay for our intransigence and, as Weisman points out, there will be a day of reckoning.

Principles such as loving one’s neighbor as oneself, being each other’s keeper, and looking after our land are positive steps that can be taken today. They represent the way of life our Creator laid out as the source of blessings (Deuteronomy 28:1–6). These are timeless universals, applying to each of us across the board: the families we have, the homes we build, and the way we eat.