Toward a New Normal

Fighting Loneliness and Social Disconnection

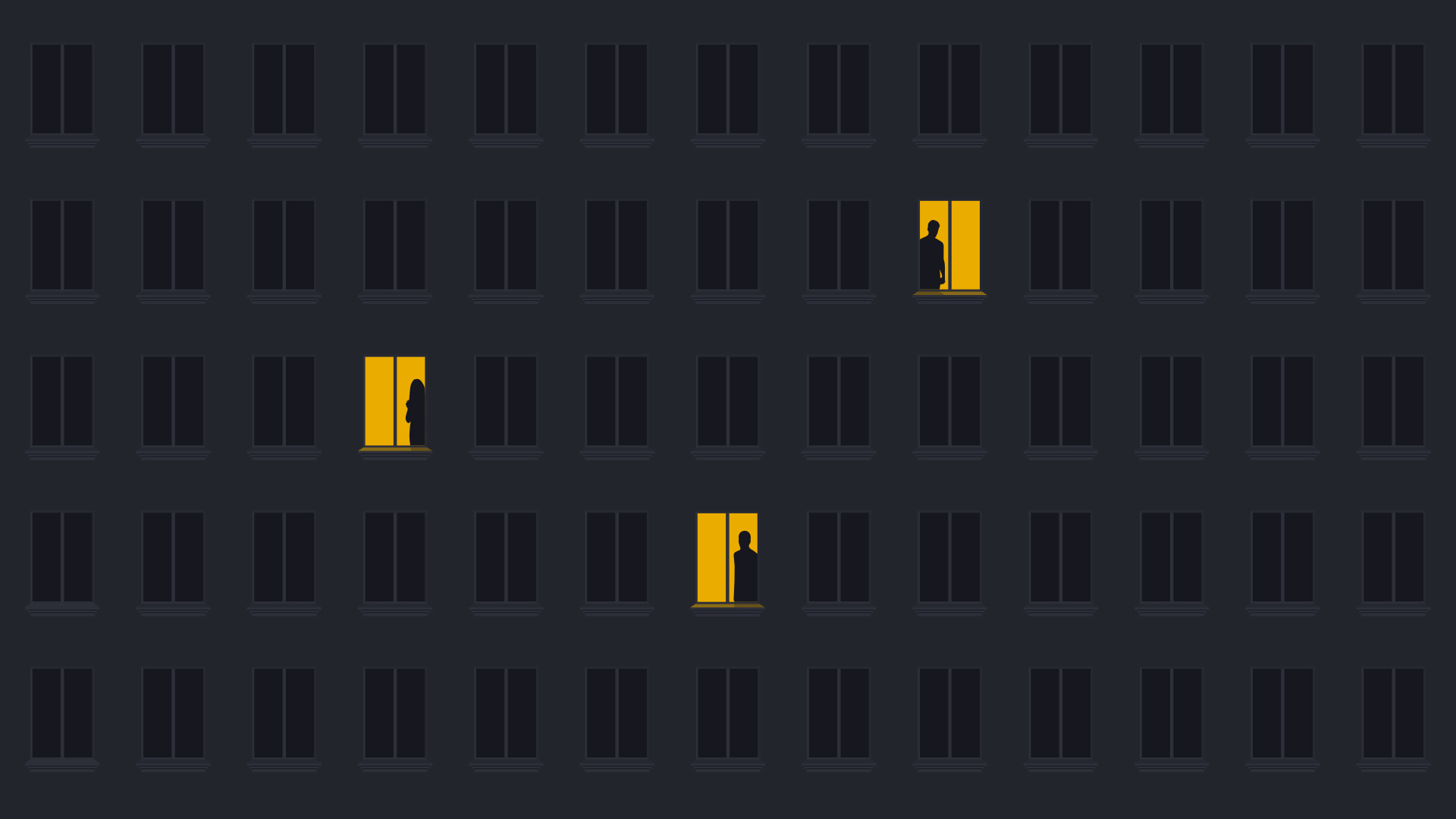

For many, loneliness and social isolation were already a part of life before COVID-19. They may not want to go back to the way things were. In The Lonely Century, Noreena Hertz explains how things can and must be different going forward.

The Lonely Century: How to Restore Human Connection in a World That’s Pulling Apart

Noreena Hertz. 2021. Random House, Currency, New York. 384 pages.

As the COVID-19 pandemic drags on, many are asking, “When will we get back to normal?” Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and, for many, the face of America’s scientific-medical response to the pandemic, suggested in a January 2021 interview that if we could get 70–85 percent of the people in the United States vaccinated, “we could develop a degree of herd immunity that would have a major impact on slowing down this outbreak; and hopefully, by the fall of 2021, we could start approaching some degree of normality.”

While such dates are a moving target, the desire to get this behind us is palpable. Other nations are likewise trying to return to a pre-pandemic state, and they see vaccinating their respective populations against the virus as an essential step to that end.

In the meantime, though, we might ask ourselves what we’ve learned during this year of quarantine and isolation. Noted economist, author and broadcaster Noreena Hertz suggests in The Lonely Century that just as the novel coronavirus has in many cases aggravated other physical health problems, so it has worsened the problem of loneliness that already existed: “The Lonely Century did not begin in the first quarter of 2020. By the time COVID-19 struck, many of us had already been feeling lonely, isolated, and atomized for a considerable amount of time.”

Her book describes the reasons for this and outlines how we can reconnect—a crucially relevant goal with or without pandemic conditions. Citing a long-emerging “Loneliness Economy” that not only enables a contactless existence but then exploits those who feel alone, she adds, “Inevitably, months of lockdowns, self-isolation, and social distancing have made this problem even worse.”

Hertz is not the first to highlight the loneliness epidemic. Former US surgeon general Vivek Murthy (who at time of writing awaits confirmation to the same post in the Biden administration) also wrote a book on the subject.

“When we strengthen our connection with one another, we are healthier, more resilient, more productive, more vibrantly creative, and more fulfilled.”

Hertz and Murthy are among many who have at times described the effect of loneliness as the equivalent of smoking 15 cigarettes a day. As serious as loneliness is, however, it’s worth mentioning that this often-repeated declaration misstates researcher Julianne Holt-Lunstad’s findings, from which the statistic is drawn. In her paper, Holt-Lunstad links a lack of social connection (a broader term than loneliness) to the adverse health effect so often cited. “Social isolation and loneliness are distinct experiences, but both are characterized by a lack of social connection,” she writes. “I think people assume ‘lacking social connection’ is the same as ‘loneliness’ but it is not,” Holt-Lunstad explained when we asked her to clarify. “Loneliness is a form of low social connection, but not the only indicator.”

As we’ll see, Hertz goes on to explain that her own definition of loneliness is fairly broad.

Defining the Problem

The Lonely Century invites us to ask ourselves, “Am I lonely?” It’s a good place to begin, as it can establish a baseline and indicate how much we may personally need the information in the rest of the book. To answer effectively, Hertz encourages the reader to complete a 20-question quiz known as the UCLA Loneliness Scale, which is “designed to ascertain not only how connected, supported, and cared for respondents feel, but also how excluded, isolated, and misunderstood.” The scale has been around since 1978 and is widely used. Those who score over 43, says Hertz, would be considered lonely. But even if we fall below that threshold, the book’s real value lies in suggesting ways in which we can help the many who will score higher.

Hertz next offers an important caveat so readers are clear on her terminology: “A key difference between my definition of loneliness . . . and the traditional one is that I do not define loneliness only as feeling bereft of love, company, or intimacy. Nor is it just about feeling ignored, unseen, or uncared for by those with whom we interact on a regular basis: our partner, family, friends, and neighbors. It’s also about feeling unsupported and uncared for by our fellow citizens, our employers, our community, our government. It’s about feeling disconnected not only from those we are meant to feel intimate with but also from ourselves. It’s about not only lacking support in a social or familial context, but feeling politically and economically excluded as well.”

“I define loneliness as both an internal state and an existential one—personal, societal, economic, and political.”

Throughout The Lonely Century, Hertz clearly and engagingly addresses all four aspects of her definition by linking loneliness and its effects to relatable areas of life—from living alone in an urban condo, to no-contact shopping, to the effects of social media and our always-on smartphones. She explains how the COVID-19 pandemic has led to many being even more solitary (if only temporarily), and then focuses on what we can do as individuals as we anticipate a return to normal. How can we proactively engage, or reengage, with our communities in a way that serves as an antidote to loneliness—our own and that of others? Her suggestions amount to a vaccine of the mind, not just to fight but to prevent loneliness in the first place. It’s an essential aspect of confronting what is in effect a two-headed monster: COVID-19

Socially Distant

Throughout the book, Hertz brings up one or multiple solutions to each issue she raises, advocating both for personal responsibility and for conscious, engaged actions in the community.

On the individual level, for example, her suggestions are as simple as taking the time to say hello as we pass others in a hallway or wait in line at the grocery store. Six feet, or a meter or two (depending on where we are in the world), between individuals isn’t a concrete wall. But too often we’re looking down at our screens, earbuds in, completely oblivious to and disengaged from those around us. Micro-interactions on a daily basis, says Hertz, would do much to stem the effects of loneliness.

Hertz believes that individuals, businesses and government (at both the local and the national level) need to work together to combat the problem: “If we are to mitigate loneliness not just at an individual level but also at a societal one, we urgently need the dominant forces that shape our lives to wake up to the scale of the problem. Government, business, and we as individuals all have significant roles to play.”

“The loneliness crisis is too complex and multifarious for any one entity to solve on its own.”

At the societal level, Hertz encourages the post-pandemic return of bustling Main Streets and High Streets. She hopes for a rejuvenation of local businesses to counter e-commerce and the power that large corporations wield with their low prices, calling for governments to pass legislation to make that possible.

For instance, give the mom-and-pop coffee house a chance against the coffee megachains, because there’s something about that local flavor that actively contributes to the community for the benefit of all. Unfortunately, many local establishments around the world are eventually forced to shut down because rents are too high, ingredients are too expensive, or the laws aren’t favorable. As Big Coffee partners with Big Tech to “personalize” the coffee experience through artificial intelligence, the viability gap only widens further. And if the mom-and-pop down the street isn’t yet offering free high-speed Internet access like the major chains do, customer loyalty may be tested to the breaking point. Yet customer choice is always personal, and it will always have consequences. Do we go to a coffee shop for the truly personal experience of engaging with others, or to focus on a screen while surrounded by others doing the same?

As Hertz points out, “some of this is about taking small steps that may not seem much at first glance, but over time will accrue meaningful impact. Things like bringing biscuits into the office to share with colleagues or putting our phones away and being more present with our partners and families.”

She goes on to say, “It’s a shift in mindset that is needed. We need to recast ourselves from consumers to citizens, from takers to givers, from casual observers to active participants. This is about taking opportunities to exercise our listening skills, whether in the context of work, our family lives, or in our friendships. It’s about accepting that sometimes what’s best for the collective is not what’s in our own immediate self-interests.”

In The Lonely Century, Hertz explains how things can and must be different going forward, because returning to the way things were before COVID-19 means allowing loneliness to continue and to worsen. You can’t kill just one head of the two-headed monster; you have to attack both. Of the two, loneliness is the more difficult to defeat because basic public health measures and a jab or two in the arm won’t fix it. It’s much more difficult to motivate human beings to take responsibility and change their behavior, first at the personal level and then at a societal level.

Simply stated, Hertz doesn’t believe we should return to status quo but should consciously live in a way that will make the post-COVID-19 world different. “The more we contribute to our neighborhood,” she contends, “the more vested in it we become and the more real the community feels.” Her hope is that by considering the various points she raises, and then following through to make substantive changes in how we look out for one another, we can enjoy a new normal—both personally and collectively.