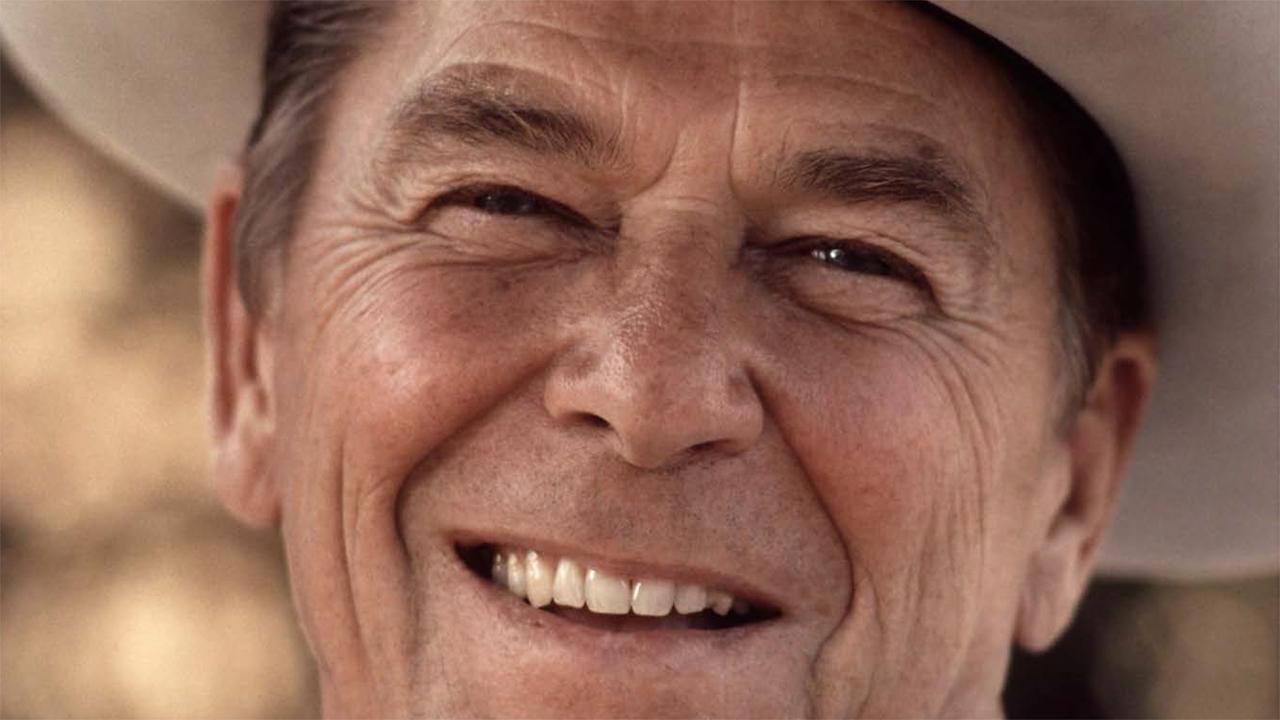

Ronald Reagan: The Eternal Optimist

According to the US Constitution, the qualifications for president are rather simple: be a natural-born citizen who has lived in the United States for 14 years or more, and be at least 35 years old. The historical record, however, suggests that the candidate also become a lawyer or a war hero; add a session or two in Congress, and election might be inevitable.

Only four of the 43 men who have served as president have not fit some combination of the latter criteria. Ronald Reagan is one. Born in 1911 in Tampico, Illinois, he was the second son of Jack and Nelle Reagan. The family, destabilized by Jack’s alcoholism, moved several times to chase opportunities that never fully materialized. Nelle counseled her sons to have patience with what she called their father’s “sickness.” Ron grew to share her ever-optimistic view, recalling that she “always expected to find the best in people.”

As a boy, Reagan didn’t realize that he was very nearsighted. “I never knew there were leaves on the trees,” political advisor Michael Deaver recalls him saying. “I never knew what a butterfly was. I could never see the blackboard and was never picked for a team until I got my glasses.” Yet he read voraciously and had a very good memory, which helped him in school as well as in his later life.

In 1928 Reagan enrolled at Eureka College in Illinois, where he got involved in sports, theater and campus politics. He played football, was named captain of the swim team, became student body president, and in 1932 graduated with a degree in economics and sociology. His love of sports led to a job as sports announcer at a small radio station in Iowa. Though not actually on location at the games he announced, Reagan had a remarkable ability to engage his audience by embellishing the wire reports with anecdotes, player information and imagined crowd reactions. When Des Moines megastation WHO merged with his small station, he became a commentator for the Chicago Cubs and traveled with the baseball team to spring training in California, ostensibly to gather insights that would deepen the broadcasts.

From Studios to Oval Office

While in Hollywood in 1937, Reagan followed the habit of many visitors to the movie capital: he made a screen test. His voice caught the attention of casting directors, and before long he was under contract to make several movies a year; his best-known role was perhaps that of “the Gipper” in 1940’s Knute Rockne, All American.

Reagan’s poor eyesight kept him from combat duty during World War II. Instead he made training films for the Army Air Force, rising to the rank of captain by war’s end. At the time he was newly married to actress Jane Wyman, with whom he had a daughter, Maureen, and then adopted a son, Michael. A second daughter, Christine, died at birth, and in 1949 the couple divorced.

During his time in Hollywood, Reagan became politically active as president of the Screen Actors Guild and a supporter of various Democratic candidates for public office (he was a registered Democrat at the time). After the war, during the Joseph McCarthy era of communist witch hunts, the actor served as an informant to the FBI. Reagan felt it was his duty to protect the industry and by extension the country from what he saw as the creeping threat of communism.

In 1952 he married actress Nancy Davis. They had two children, Patti and Ron, and remained extremely devoted to one another over the years.

“The secret to Ronald Reagan is that there really is no secret. He is exactly the man he appears to be.”

As his film career wound down, Reagan took a job hosting a weekly television series, The General Electric Theater. His responsibilities included traveling the country as a corporate goodwill ambassador, giving speeches at GE’s 139 plants as well as for business groups in each community. Based on audience feedback, his topic gradually turned from Hollywood to the value of personal enterprise in the face of wasteful and intrusive government programs. The TV host’s public-speaking skills became increasingly well known, and, having recently changed his party affiliation to Republican, he was invited to give a speech in support of conservative Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign—a speech that turned the eyes of the Republican party in his direction. Yet when approached to run for public office, Reagan was reluctant. “I’d never given a thought to running for office and I had no interest in it whatsoever,” he wrote later. “After doing as much research as I had on the operations of government, the last thing I wanted was to become a part of it. I just wanted to keep on making speeches about it.”

But once he joined the political arena, Reagan was unstoppable. In 1966 he toppled career politician Edmund Brown Sr. to become governor of California. After two terms he chose not to seek reelection, instead making an unsuccessful bid for the 1976 Republican presidential nomination. Four years later, however, he won a landslide victory over Jimmy Carter and was sworn in as America’s 40th president; at 70, he was the oldest man ever to be elected to that office.

In the early days of his administration, Reagan and his team engaged in energetic negotiations with the Washington establishment over budgets, deficits, inflation, housing, energy, defense and international relationships. But the Reagan Revolution, as it would later be called, began bogging down. Then in March 1981, less than 100 days into his presidency, a would-be assassin’s bullet caught Reagan just under the left arm as he was leaving a speaking engagement in Washington. The president’s strong recovery from the incident gave him a renewed imperative. He told Deaver, now his White House Deputy Chief of Staff, “I came to a conclusion about something when I was in the hospital. There must be a reason why I was spared. From now on, I’m going to follow my own instincts.” As his presidency continued, those instincts focused increasingly on national defense and nuclear weapons.

Nuclear Madness

Initiating START (the STrategic Arms Reduction Treaty) in 1982, Reagan proposed to the Russians the gradual elimination of nuclear weapons. In a commencement address at his alma mater, the president noted that “the monumental task of reducing and reshaping our strategic forces to enhance stability will take many years of concentrated effort. But I believe that it will be possible to reduce the risks of war by removing the instabilities that now exist and by dismantling the nuclear menace. . . . I’m confident that together we can achieve an agreement of enduring value that reduces the number of nuclear weapons, halts the growth in strategic forces, and opens the way to even more far-reaching steps in the future.”

He had long felt that the threat of nuclear war was one of the world’s most pressing concerns and that “the MAD [mutually assured destruction] policy was madness,” but he also believed that the Russians had to be dealt with from a position of strength. “I wanted a balanced budget,” the president later recalled. “But I also wanted peace through strength.” He insisted that “if you were going to approach the Russians with a dove of peace in one hand, you had to have a sword in the other.”

By 1983 the president’s “dream of a world free of nuclear weapons” had morphed further: he began to ask about the possibility of a technology that could intercept and destroy ballistic missiles before they could impact their targets. In a nationally televised speech from the Oval Office, he announced the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI): “I call upon the scientific community in our country, those who gave us nuclear weapons, to turn their great talents now to the cause of mankind and world peace, to give us the means of rendering these nuclear weapons impotent and obsolete.” He concluded: “My fellow Americans, tonight we’re launching an effort which holds the promise of changing the course of human history.”

“I have approved a research program to find, if we can, a security shield that would . . . render nuclear weapons obsolete. We will meet with the Soviets, hoping that we can agree on a way to rid the world of the threat of nuclear destruction.”

While it seemed a worthy objective, many critics thought it was beyond the technology of the day to create; within days of its announcement, the program became mired in bitter controversy. Still, in the following years billions of dollars were poured into research on the possibility.

The Soviets, too, pushed back. At the 1986 Reykjavik summit with Mikhail Gorbachev, Reagan refused to give up further SDI research in concession to Soviet promises of nuclear and conventional arms reductions: “I realized he had brought me to Iceland with one purpose: to kill the Strategic Defense Initiative. . . . I was very disappointed—and very angry.” Reagan walked out on the summit.

By 1991, under his successor George H.W. Bush, the so-called Star Wars program had shifted from being a “shield” protecting the nation’s civilian population in a full-out superpower exchange, to a more limited system meant to neutralize a small rogue attack.

California Sunset

The Reagans returned to California after his second term in office ended. In 1994, the former president wrote a letter to the people of the United States informing them of his battle with Alzheimer’s. His love of country was obvious as he stated, “When the Lord calls me home, whenever that may be, I will leave the greatest love for this country of ours and eternal optimism for its future. I now begin the journey that will lead me into the sunset of my life. I know that for America there will always be a bright dawn ahead.”

Ronald Reagan died in 2004; his legacy is complex, but his view of American greatness is central to it. He viewed the American people as the strength of the nation. His patriotism was of a type that saw the United States as nothing short of a “shining city”—a beacon for the rest of the world.

“Reagan did, in fact, have a vision of what he wanted the world to be like,” writes biographer Lou Cannon. “It was the vision expressed in the [1982] Westminster speech: the Berlin Wall torn down, pluralism and human rights in the Soviet Union, free elections in Poland and in every Communist country in the world. Above all, it was a vision of a world safe from the threat of nuclear Armageddon that he had referred to in the Westminster speech as ‘predictions of doomsday.’ But Reagan’s ‘guiding star’ was a dream, not a foreign policy. It was a dream embodied in the Strategic Defense Initiative. . . .”

Cannon describes Reagan’s ability to project an “everything is going to be alright” persona as his “most distinctive quality as president.”

Deaver adds, “He didn’t have trouble conveying confidence because he was sure of what he thought. He didn’t have to fake it, his acting ability aside. His steady sense of purpose grew from his complete acquiescence to a drummer only he could hear.”