Evolution: Science's Center of the Universe

“Who are you?” is not an unusual question. “What are you?” on the other hand, is something you may never have been asked and probably have never asked of yourself. Are you an accident of the universe, a chance occurrence resulting from the interaction of atoms and molecules over the past several billion years? Or are you the result of a very specific and purposeful act of creation? Your answer to the question “What are you?” profoundly impacts what you think of yourself and the world around you.

Ours is a world that is visibly dominated by scientific discoveries; knowledge has increased exponentially, producing an unending stream of technological innovations. Yet our world is also dominated by various competing philosophies. Though it’s perhaps not as obvious, these philosophies have a greater effect on us than all of our technology combined, because how we view ourselves and our world determines what we do with the knowledge at our disposal.

Science and philosophy are often viewed as opposite approaches to understanding: science as a search for hard facts based on observation, experimentation and measurement so we can better understand the workings of the world around us; philosophy as a search for a general understanding of why things are the way they are, based on speculative reasoning and logic.

Yet the two are inextricably tied together. For instance, science without a decent moral philosophy to direct it produced the nightmarish world of Hitler’s Nazi Germany. In that setting some scientists were directed toward eugenics in an attempt to produce a superior race of human beings. At the same time, technology was also used in an attempt to exterminate those human beings who were considered undesirable. Clearly, scientific endeavor without proper moral restraint can produce horrific results.

Philosophy Unchecked

Likewise, philosophy disconnected from the check of reality can spin out of control. Such was the situation in Catholic Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Roman Catholic Church had long accepted certain views about the nature of the world as put forward by the Greek philosopher Aristotle. In his attempt to understand causes, Aristotle developed views about the natural world based on logic and reason. A glaring weakness in his approach was a lack of practical observation to confirm or negate his conclusions. Because his flawed theories became wedded to the doctrine and authority of the church and ostensibly to the teachings of the Bible, a serious problem developed.

Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus bucked the tide of conventional Aristotelian wisdom with regard to the natural world. His ideas set off a firestorm when Italian mathematics professor Galileo Galilei later affirmed by experimentation and measurement that some of Aristotle’s conclusions were in error. When Galileo published his findings, he became the target of intense opposition from fellow academicians, who saw in his arguments an attack on Aristotle and the entire philosophical scheme that defined the established view of the world.

“In Aristotle’s science every part was linked logically to every other, so it seemed to his followers that nothing he said could be wrong.”

As explained by Stillman Drake in his biography of Galileo, “in Aristotle’s science every part was linked logically to every other, so it seemed to his followers that nothing he said could be wrong.” Thus criticism of any of Aristotle’s views was a threat to his entire scheme.

In contradiction to one of Aristotle’s positions, Galileo famously pointed out that the rate at which a body falls is not proportional to its weight. The blind opposition of Aristotelian philosophers led one of them to conduct experiments to disprove Galileo’s claim. In his book Dialogue Concerning Two New Sciences, Galileo responded: “Aristotle says that a hundred-pound ball falling from a height of a hundred cubits hits the ground before a one-pound ball has fallen one cubit. I say they arrive at the same time. You find, on making the test, that the larger ball beats the smaller one by two inches. Now, behind those two inches you want to hide Aristotle’s ninety-nine cubits and, speaking only of my tiny error, remain silent about his enormous mistake.”

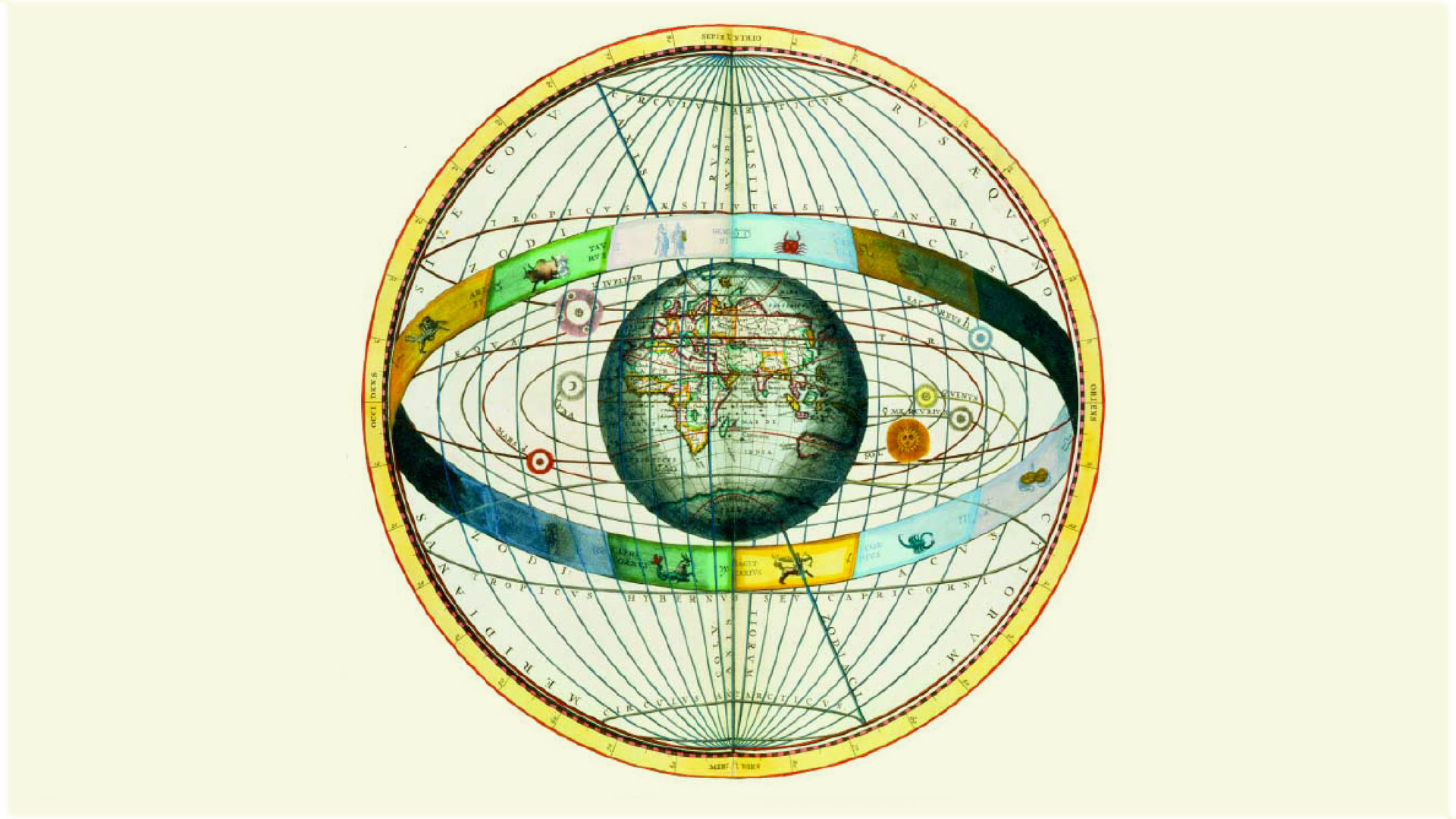

Another accepted view in Galileo’s day was that the earth was the center of the universe, unmoving and unmovable. This belief was based on Aristotle’s principles, which had been further developed by second-century astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, and maintained that the celestial bodies (sun, moon, planets and stars) revolved around the earth. It also included the idea that celestial bodies were free from any imperfection and couldn’t be changed. After constructing a 20-power telescope, Galileo found evidence that the accepted earth-centered, perfect-orbed view of the universe was also in error.

Drake explains that in 1609, while observing the moon, Galileo “correctly interpreted what he saw as proving the existence of mountains and craters where natural philosophers demanded perfect sphericity in the perfect heavens. Early in January 1610 he discovered four satellites revolving around Jupiter, contradicting the idea of natural philosophers that the earth was the centre of all celestial motions.”

A few months later, Galileo published his findings in a paper titled “Starry Messenger,” which was vehemently denounced by those defending Aristotle. Six years later, theologians of the Roman Catholic Church officially censured Galileo’s propositions that the sun is the center of the “world” and that the earth moves around the sun as well as on its own axis. They based their censure edict on commonly held philosophy and on their view of the meaning of certain Bible passages. Galileo was thus forbidden to defend or, according to one disputed document, to teach these two propositions.

In 1632 Galileo published a paper discussing the opposing Ptolemaic [earth-centered] and Copernican [sun-centered] systems, believing he was safe as long as he treated any motion of the earth as merely hypothetical. The following year, however, he was brought before the Inquisition on suspicion of heresy. He was found guilty and lived under house arrest until his death in 1642.

Thus philosophy temporarily triumphed over verifiable observation and measurement, to the great discredit of the Roman Catholic Church and the philosophers.

Modern Counterpart

How are these events of 400 years ago relevant to the present? The connection is that Western society finds itself dominated today by another deficient philosophy: Darwinian evolution, or evolution by natural selection. The view that life in all its diversity and complexity evolved from inorganic elements by totally materialistic, unguided processes is put forward by its proponents as an unquestionable fact. In reality, it is a philosophical construct supported by many questionable, misleading and, in some cases, blatantly fraudulent statements.

That plants and animals have changed remarkably over the long history of life on earth is an observable fact. That plants and animals can vary within a species (popularly called micro-evolution) has been observed. However, no one has ever seen any plant or animal evolve into another kind of plant or animal (often referred to as macro-evolution).

Animals and plants can be varied by selective breeding, but in spite of all the human intervention involved in producing, for example, a vast variety of dogs, a dog is a dog is a dog. The variations are the result of carefully selecting and breeding individual dogs to emphasize specific genetic traits that were inherent in the dog genome all along. Changes in the genome occur, but such mutations have never been shown to produce a viable new species. In addition, no one has ever manufactured a living organism from the basic elements that make up all living things (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, etc.), let alone demonstrated how nonliving materials could organize themselves into a living organism.

Thus the idea that living organisms could spontaneously originate and subsequently differentiate by natural means into other kinds of organisms over time is not an observed fact. It cannot be demonstrated by repeatable experimentation, observation and measurement, which are essential to the scientific method. Evolution by natural selection therefore remains only an idea, a way of interpreting certain facts, but not a fact in itself. As in the natural philosophy of Galileo’s time, speculation is being relied upon as evidence.

Natural philosophers before and during Galileo’s life created elaborate cosmological schemes to explain the movement of the sun, moon, planets and stars based on their assumption that the earth stood still—unmoving and unmovable. Though they produced explanations that seemed to account for the observed motions of celestial bodies, their explanations were a waste of time and effort because they were based on an invalid premise.

Unconvincing Evidence

A similar situation exists today in the field of evolution research: an assumption is being supported by elaborate but faulty arguments. In the book Icons of Evolution (2000), Jonathan Wells, who holds a doctorate in molecular and cell biology, lists 10 of the most commonly cited evidences for Darwinian evolution.

He then points out: “These . . . are so frequently used as evidence for Darwin’s theory that most of them have been called ‘icons’ of evolution. Yet all of them, in one way or another, misrepresent the truth. . . . Some . . . present assumptions or hypotheses as though they were observed facts. . . . Others conceal raging controversies among biologists that have far-reaching implications for evolutionary theory. Worst of all, some are directly contrary to well-established scientific evidence.” Wells proceeds to point out the difficulties and errors in the most common arguments used to support the theory of evolution.

He is not alone in his objection to the commonly held view that life evolved apart from an intelligent outside agent. In Darwin’s Black Box (1996), biochemist Michael Behe points out that Darwinian evolution, with its gradual step-by-step mechanism, cannot account for irreducibly complex biochemical machines found within cells. These mechanisms provide convincing evidence for the intelligent design of living organisms.

William Dembski, a mathematician and proponent of intelligent design as a better explanation for the origin of life, upbraids mainstream theologians for their acceptance of Darwinism. The design theorists’ critique of Darwinism, he says, “is not based on any supposed incompatibility between Christian theism and Darwinism. Rather, they begin their critique by arguing that Darwinism is on its own terms a failed scientific paradigm—that it does not constitute a well-supported scientific theory, that its explanatory power is severely limited, and that it fails abysmally when it tries to account for the grand sweep of natural history.”

“Darwinism is on its own terms a failed scientific paradigm.”

He continues: “The problems facing Darwinism are there, and they are glaring: the origin of life, the origin of the genetic code, the origin of multicellular life, the origin of sexuality, the gaps in the fossil record, the biological big bang that occurred in the Cambrian era, the development of complex organ systems, and the development of irreducibly complex molecular machines are just a few of the more serious difficulties that confront every theory of evolution that posits only purposeless, material processes” (“What Every Theologian Should Know About Creation, Evolution and Design”).

How Could It Be Wrong?

Though Wells, Behe and Dembski are not alone in their rejection of Darwinian evolution, they are among a distinct and small minority of scientists who take this view. Given the near unanimity among scientists that Darwinian evolution is correct, how could it be wrong? Having seen so many advancements in understanding the nature of the physical world and so many useful applications of knowledge, our society rightly has a very high regard for scientific achievement and for scientists in general.

Scientists, however, like the rest of humanity, are limited in their understanding and are susceptible to being misled. Most scientists do not specialize in areas that relate to evolution. They will usually have studied general science and biology as young students and will for the most part have unquestioningly accepted the idea of evolution because their teachers and their textbooks said it was so. A student just learning the basics of a subject does not have the facts available to refute those who are authorities in a given field.

Scientists, like the rest of humanity, are limited in their understanding and are susceptible to being misled.

As a result, as Wells points out, “most biologists are unaware of [the controversies]. . . . Most of what they know about evolution, they learned from biology textbooks and the same magazine articles and television documentaries that are seen by the general public. . . . Some biologists are aware of difficulties with a particular icon because it distorts the evidence in their own field. . . . But they may feel that this is just an isolated problem, especially when they are assured that Darwin’s theory is supported by overwhelming evidence from other fields.”

Any scientist considering the problems with Darwinism has a serious obstacle to confront, because Darwinism is such an entrenched belief. In the November-December 2000 issue of American Outlook, Dembski discusses the danger of a scientific theory becoming an unquestioned dogma.

“A simple induction from past scientific failures,” he writes, “should be enough to convince us that the only thing about which we cannot be wrong is the possibility that we might be wrong. . . . Dogmatism, however, deceives us into thinking that we have attained ultimate mastery of information and that divergence of opinion is futile. . . . The issue is whether the scientific community is willing to set aside dogmatism and admit as a live possibility that even its most cherished views might be wrong. . . . Like any other scientific theory, Darwinism needs periodic reality checks” (“Shamelessly Doubting Darwin”).

Far-Reaching Intolerance

Though Darwinian evolution is not a hard, demonstrable fact of science, it has become the dominant scientific worldview. As such it has had and continues to have a far-reaching impact, not only on science and education but also on society as a whole.

Darwin supplied those who wanted to dispense with the idea of God a means to do so. Historian Gertrude Himmelfarb points out that “there were many who agreed with [Thomas] Huxley that one of the great merits of the theory of evolution was its ‘complete and irreconcilable antagonism to that vigorous and consistent enemy of the highest intellectual, moral, and social life of mankind—the Catholic Church.’ And not Catholicism alone but all religion” (Darwin and the Darwinian Revolution, 1959).

The irony is clear. Those who might question the validity of Darwinian evolution are subject to harsh judgment from society’s intellectual establishment not altogether different from the judgment of the Inquisition that condemned Galileo in 1633. Aristotelian philosophers at that time vehemently attacked him because his criticism of Aristotle threatened the entire framework through which they viewed the world. A similar situation exists today with proponents of Darwinian evolution. Discussion of other possible explanations and criticism of organic evolution are simply not tolerated.

As if to put in the final word on the subject, Richard Dawkins, a leading proponent of evolution, famously had this to say about those who question evolutionary dogma: “It is absolutely safe to say that, if you meet somebody who claims not to believe in evolution, that person is ignorant, stupid or insane (or wicked, but I’d rather not consider that).”

It seems absurd in this Western world to suggest that Darwinian evolution is not an absolute truth; that it is, in fact, only an idea—a very compelling idea for those who would rather not consider whether an intelligence far greater than their own is responsible for their very existence and may even have a definitive answer to the question “What are you?”

Darwinism is a philosophical construct used to explain the development of life without a creative intelligence behind it. As a philosophy it has become dangerous because it is wedded to the power structure in society, which can effectively quash those who dissent.

Things haven’t changed that much in the past 400 years.