The Descent of Darwinism

How did natural selection come down to us as the dominant view of origins?

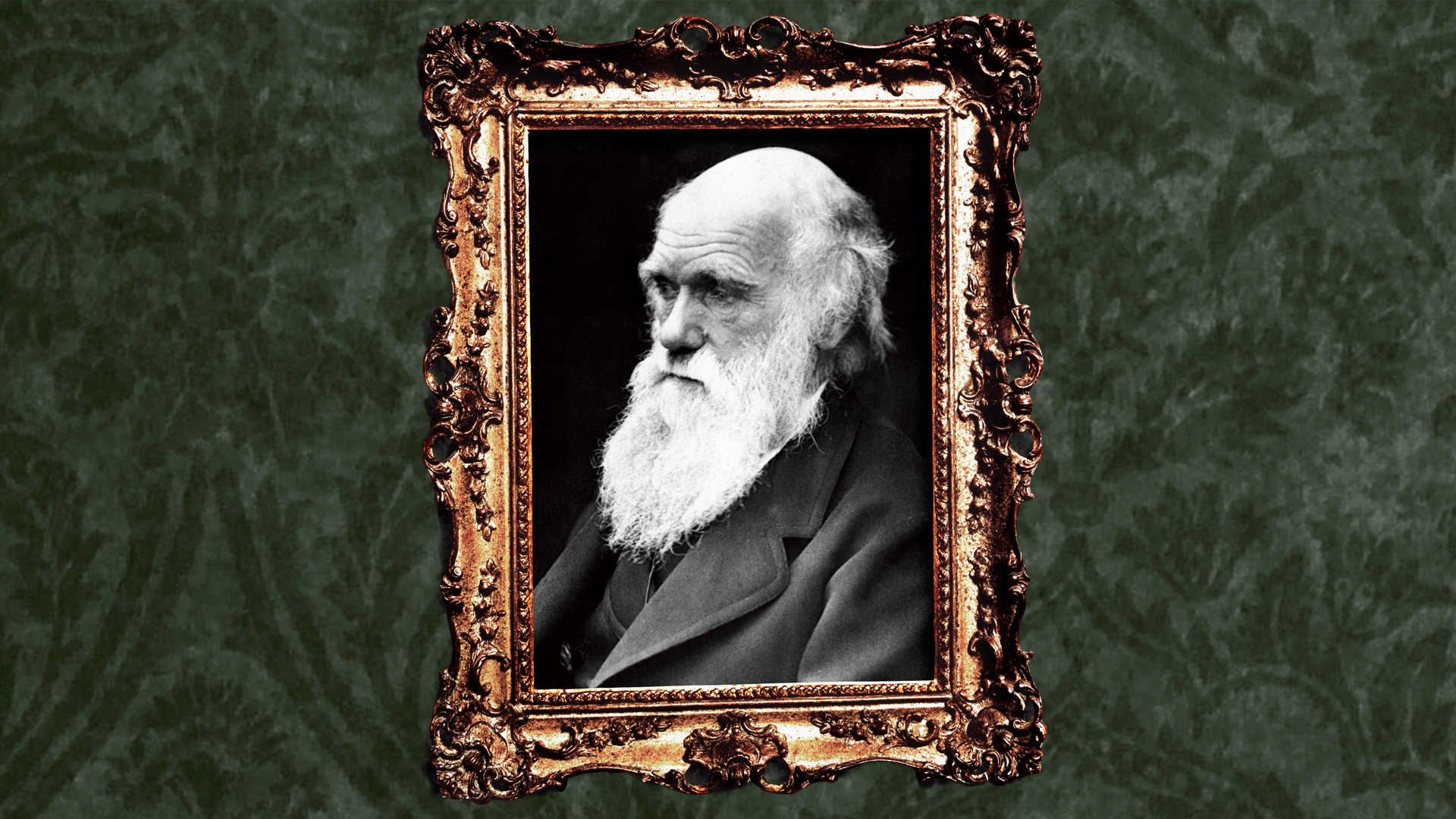

In 1859 the first edition of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published. Over several hundred pages, Darwin made what he called “one long argument” for his conclusion that natural selection provided a means for the transmutation, or evolution, of new species. This was clearly a challenge for the orthodoxy of his day—the idea of Special Creation and the fixity of species as interpreted from the Genesis creation account.

His argument struck down both the need for and the purpose of a First Cause, a Special Creator. From his study of nature, combined with his well-known voyage to the Galapagos Islands and around the globe, Darwin synthesized an explanation of both the unity and the diversity of life without the necessity of God.

That evolutionary perspective has, of course, carried down to us today, having had more than 150 years to not only permeate all areas of academic study but to color our sense of who we are and why we are here. But while the tenets of natural selection remain intact, many of Darwin’s other ideas—concerning how variation occurs, for example—have not held up.

Modern biology finds a lot that is wrong in Origin of Species. Could it be that Darwin also misunderstood the biblical message concerning origins, a misunderstanding that has likewise descended to us today?

“Darwin did not change the islands, but only people’s opinion of them. That was how important mere opinions used to be back in the era of great big brains.

“Mere opinions, in fact, were as likely to govern people’s actions as hard evidence, and were subject to sudden reversals as hard evidence could never be. So the Galápagos Islands could be hell in one moment and heaven in the next, . . . and the universe could be created by God Almighty in one moment and by a big explosion in the next—and on and on.”

Branching Out

The phrase “descent with modification” was paramount in Darwin’s thinking. He noted that from the time of life’s first beginnings, changing environmental conditions would challenge living things to change in order to survive. Natural selection was his explanation for how life could adapt automatically, without the need for a Creator or Designer at the helm. From this perspective, all life on earth, including humans, arose from a common ancestor and diversified through time and chance to become the vast number of species we see today. But the mystery of the origin of life is as unsolved today as it was in Darwin’s time, when even the cell theory was only in its infancy.

The idea of the evolution of life did not originate with Darwin; it has been around for thousands of years, and by the 1800s there was little doubt that life had changed over the course of the earth’s history. The question was how and why? Contemporary opinions on evolution, presented by J.B. Lamarck, Georges Cuvier, Louis Agassiz and Robert Chambers, for example, all viewed the process as in some way divinely ordered and/or purposeful.

It was this doctrine of design and purpose, the teleological view, that Darwin insisted was incorrect. Selection, he insisted, was an undirected natural process that had no particular end in mind. Human beings are not God’s crowning creation; rather, we are one twig at the end of one branch of evolution’s great tree of life.

More axiom than theory, the concept of natural selection codifies a rather obvious observation: the individuals best adapted to their environment will produce more surviving offspring. Given enough time, Darwin believed, new species will gradually develop from this process. This fork-in-the-road or branching pattern of descent has become the bedrock concept of evolutionary theory today. It is the key unifying theme that ostensibly reveals the meaning of both the geologic fossil record and the genetic record found in the DNA of all life.

A Darwinian View of Life

Although he used a surprising number of phrases suggesting purpose and beneficence in the adaptive process, Darwin could not reconcile the immutable “kinds” and the short time frame he understood from the Genesis creation account with his experience of artificial selection, or selective breeding. Evidence of the earth’s long geologic history also seemed to compromise the Genesis account.

Combining a long time frame, as put forward in Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830), with the Malthusian dilemma of too many mouths and too little food, Darwin interpreted the struggle for survival he observed in the world as the competitive force that would move life forward.

“When we reflect on this struggle, we may console ourselves with the full belief, that the war of nature is not incessant, that no fear is felt, that death is generally prompt, and that the vigorous, the healthy, and the happy survive and multiply.”

Support came from others who had arrived at the same conclusion. Alfred Wallace, working in the tropics, deduced almost the same formula independently. More importantly, though, in contrast to the deist view of his time, Darwin insisted that the loving, caring Creator of Scripture could not have authored the world of waste, competition and survival-of-the-fittest that he saw.

“Trying to pin Darwin down on the topic of religion is impossible,” Peter J. Bowler told Vision, “because he himself admitted he was confused and vacillated back and forth between real skepticism and a vague hope that one might be able to see an ultimate purpose behind all the suffering and uncertainty of evolution.” Bowler is a historian of biology and has written extensively on Darwin’s influence. He added, “The death of his daughter was a real issue for him in destroying the last vestige of belief in a personal, caring God; but that chimed in with his increasing sense of the cruelty of nature, which meant that any God had to be freed from personal responsibility for the details (by reducing him to a distant First Cause). But if you go too far down that track, is there any point left in believing in it/him?”

Indeed, that is the question. If the universe runs on autopilot, where is the need for God? Proponents of what Darwin described as the “grandeur in this view of life” have long insisted that On the Origin of Species brought the study of nature out of the church and fully into the Enlightenment laboratory—from superstition into the light of dispassionate scientific investigation.

It’s true that theists, who were (and still are) wont to do constant battle against Darwinists, often followed preconceived ideas that skewed even the sincerest quest to understand the world and humankind. Human-invented doctrines of the immortal soul, the Trinity, and hell as a place of permanent suffering for the unconverted are all examples of deeply held beliefs that have no biblical basis. Thus those who are critical of the Darwinists and edgy for young-earth creationism or at least a more purpose-driven evolutionism often advance opinion over substance. Although they see themselves as God’s agents in calling for a return to scriptural foundations, they are often misguided, turning the Creator into an idol of their own imaginations.

But of course, science itself can be very much like religion: a passionate endeavor where the workers are often misled by their own preconceived ideas and expectations.

Science as Patronage

In the 18th and 19th centuries, when science was still a gentlemen’s club, it was just beginning to adopt the materialist philosophy that governs today’s professional scientist. Questions may have been posed scientifically, with the language of observation, hypothesis and theory, but most investigators held some form of deist perspective.

“It’s probably fair to say that most 19th-century thinkers, even the agnostics, accepted the idea of a First Cause,” Bowler remarked; “but the agnostics said, ‘We don’t have any clues from the world as to what that Cause is.’”

According to him, this perspective may have been a holdover from the very beginnings of scientific organizations. The first scientific group, the Royal Society of London, was founded in 1660. Soon, under the patronage of Charles II, the society began providing science advisers to the crown and lending support to the social status quo. Members of the Royal Society, according to Bowler, “had to show that their scientific activities did not threaten the stability of traditional religion.” If social constructs (such as the legitimacy of the monarchy) were part of the natural order, ordained of God, then nothing must be done to undercut the Creator’s purpose. Thus, in accordance with the social order of the day, the learned gentlemen of the sciences took seriously Paul’s declaration that God’s “invisible attributes,” eternal power and divine nature are evident in the natural order (Romans 1:20), even if they misapplied it politically.

“Can we wonder . . . that Nature’s productions should be far ‘truer’ in character than man’s productions; that they should be infinitely better adapted to the most complex conditions of life, and should plainly bear the stamp of far higher workmanship?”

Science could be seen, then, as a way of exploring God’s nature, a natural theology. Creating a systematic way to classify living things seemed an obvious starting point in the early 1700s, and Carl Linnaeus considered it his duty to do so. Now known as the father of taxonomy for creating the genus-species naming system, Linnaeus wrote, “If the Maker has furnished this globe, like a museum, with the most admirable proofs of his wisdom and power . . . ; it follows that man is made for the purpose of studying the Creator’s works that he may observe in them the evident marks of divine wisdom” (as quoted by John Hedley Brooke in Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives, 1991). Although the Enlightenment brought a revolution in astronomy that effectively removed Earth from the center of the universe, Homo sapiens remained the biological centerpiece of the cosmos. And just as we have not experienced any significant change in our species, so Linnaeus’s worldview presupposed the fixity of all species; although he eventually accepted the possibility of species hybridization, the phrase “according to its kind” (Genesis 1) nonetheless implied a finished biological creation.

Unnatural Theology

In this way, as presented by theologian William Paley in his early-19th-century Natural Theology, our world is one of “benevolent design,” like a finely crafted timepiece. “Nor is the design abortive,” Paley wrote. “It is a happy world after all. The air, the earth, the water, teem with delighted existence. . . . On whichever side I turn my eyes, myriads of happy beings crowd upon my view.”

If this is really so, Darwin wondered, why the transformation or mutability of species shown in the fossil record? This led to questions concerning the profound record of extinction of so many creatures. Why was there so much death and waste? Put another way, why would so many parts of a perfectly designed timepiece be discarded?

Darwin keyed his insights to the capacity of living things to reproduce exponentially and thus outstrip their food supply (a fact he gleaned from Thomas Malthus). This would lead to an inevitable struggle for survival. But if the average naturalist of that day should recognize the theological irony of such a struggle, he would simply argue that it was part of God’s general plan.

Although he was correct in not accepting this irony, Darwin was overzealous in his response. He recognized that there is a missing link in understanding a loving Creator’s relationship to a world where the struggle to survive is the bottom line. But instead of questioning the accepted view of God’s actions in the world, as proposed by natural theology, he deleted God altogether.

There are clear scriptures, however, that explain this very real missing link. They reveal that the world is suffering under the hand of a deceptive and destructive influence, another spirit working in opposition to the love of the true creator of life. Both spirits are active in the world, but with opposing agendas. Darwin conflated the two and simply could not reconcile a God who called the creation “good” and “very good” in Genesis with the struggles he observed and documented throughout the natural world.

The failure to distinguish between these two spirits is all but universal. It is the mystery of theodicy: a good God and a cruel or evil world. And while not realizing that the brutality of nature is not God’s nature is an easily made mistake, that mistake leads to a domino effect of error.

The Scriptures show that the universe and creation, of which humanity is the pinnacle, were physical and thus limited; death and decay were part of the plan. But they also plainly show that the spirit of God is not the spirit of brutality or suffering. Competition and struggle are not evidence of the spirit of God. Jesus called the source of these negative characteristics “the father of lies,” who has influenced the world “from the beginning” (John 8:44, English Standard Version). In the world overall, this disquieting and striving spirit creates what Paul referred to as “bondage to decay”—a situation seen throughout the universe (Romans 8:5–8, 20–25, ESV). It manifests itself in the human mind as a disdain for the true Creator, whose spirit is manifested as peace, kindness and patience.

If Darwin had reflected on the fullness of Scripture, which speaks to the issues that troubled him, he might have recognized the spiritual bankruptcy in the physical creation as a symptom rather than a permanent condition. The solution is not removal of the Creator but removal of the evil influence that rides over creation, followed by a restoration of the good. Such a renewal is embodied in the establishment of the kingdom of God on the earth, a coming era when God promises a reestablishment of the “good” described in Genesis (Genesis 1:10, 12, 18, 21, 25, 31; Acts 3:20–21; Revelation 21:4–5). Darwin’s great biological understanding unfortunately combined with theological error to send him down a common path: the enduring practice of removing the sovereign and loving Creator from the picture.

Darwin’s counterpoint to his critics regarding the role of variation in his theory illustrates the same kind of mistake he himself made in dismissing God. “They admit variation as a vera causa in one case,” he wrote in the final edition of Origin, but “they arbitrarily reject it in another, without assigning any distinction in the two cases.” If one replaces “variation” with “God,” the argument also holds true: those who may see God’s role in one situation often arbitrarily reject it in another. But misinterpreting the Creator’s relationship to the present world does not legitimize simply dropping His existence altogether. In the end, Darwin’s remarks were thus more accurate and had wider application than he imagined: “The day will come when this will be given as a curious illustration of the blindness of preconceived opinion.”

Beyond the Origin of Species

The bicentennial of Darwin’s birth and the 150th anniversary of the publication of his seminal work On the Origin of Species was a cover story in almost every major periodical in 2009. It was a celebratory year for the evolutionist. From the tabloids to National Geographic, what Darwin either knew about nature or didn’t know has been given wide attention. His mistakes are largely brushed aside, however; only his conclusions of random variation and survival of the fittest have gained a foothold.

The threads of natural selection are woven throughout modern thought, and understandably so, for no one (in a classic example of “six degrees of separation”) is many steps removed from the implications of his theory. Virtually any topic or debate—nature versus nurture, behavior, adaptation, dating, antibiotic resistance, color preference, camouflage, the coccyx, homology, regenerative medicine, baby care, cultural evolution, even religion—is discussed within the framework of natural selection.

To those who find a comfortable independence in the impersonal world of his conclusions, Charles Darwin is seen as a kind of biological abolitionist. The hard atheist camp continues to exclaim that his 1859 theory of natural selection freed us from slavery to religious dogma. Even those not inclined to dwell on the religious aspects of evolutionary theory recognize Darwin’s On the Origin of Species as a historical hinge, a pivot point that altered the practice of science itself. Still, the discomfort and contention arising from a theory that claims all life, including our own species, is simply the chance product of impersonal natural forces, led to a disconnect. We are social creatures involved in such myriad relationships that it is difficult to believe we are not all part of something with greater meaning, something that transcends evolutionary novelty.

“There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that . . . from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

Obviously species are endowed with genetic mechanisms that create adaptability to changing environments. In the last few decades we have even discovered the genetic code that allows for such malleability. Whether under artificial, human-controlled selection through cross-breeding, which Darwin featured as evidence of evolution before our eyes, or the natural development of new strains of microorganisms and disease, there is no doubt that life is changeable and adaptable. If this was all that Darwinism implied, there would be little if any controversy. The problem is in making these truths evidence against the existence of a Creator.

A Tangle of Theory and Theology

As they were in his time, Charles Darwin’s ideas continue to be the beacon that draws both evolutionism’s proponents and its opponents. As eminent biologist George Gaylord Simpson unwittingly demonstrates in a modern foreword to Origin, natural selection remains a process couched in its own version of teleology, or ideas about design and purpose; he speaks of “the one fully directive force in evolution, the explanation of the greatest of all evolutionary problems: the intricate adaptation of every organism to its particular way of life.” Simpson was not trying to fudge in a case for God; Darwin’s inability to reconcile nature and the Bible has carried forward in such a way that most believe there can be no common ground.

Sir John Polkinghorne is one who for decades has attempted reconciliation between Darwinism and faith. A theoretical physicist and Anglican priest, he believes that an evolutionary view is compatible with Scripture provided that selection remains true to Darwin’s non-teleological view. “We are not living in a kind of divine puppet theater; God allows creatures to be themselves and to make themselves,” he told Vision. “That is the sort of world in which we live.”

By combining the current Neo-Darwinian perspective (which combines modern genetics and natural selection) with theology, Polkinghorne finds meaning in the evolutionary “potentiality” of life to self-create. But is the Genesis account elastic enough to accommodate such a view? When we accept the world as seen through the physical limitations of a Darwinian lens, and then conclude that the only explanation for the molecular and genetic similarities between creatures is random or a playing out of brute fitness, we remain as confused and shortsighted as Darwin.

Suggesting that the scientific view of the world must accommodate both natural and supernatural, physician-philosopher Joseph Henry Green noted that there are two paths to discovering life’s meaning. These paths must not become intertwined in error. In the Hunterian Lectures of 1827, prior to the Darwinian revolution and the emancipation of science from the reality of God, Green said that “there are two ways in which a history of nature may be given. The first begins with the highest, sets out from the true and absolute First cause and ground of all; and I scarcely need add that such a history requires an inspired historian for its accomplishment.” The second way “begins from the lowest, and for its first grounds and materials takes the most general characters and properties of the objects that surround us—together with the active properties inferred from these facts, or known by immediate consciousness—In other words it begins with nature.”

Although often dismissed as a transcendentalist, Green’s conclusion is as wise today as it was before Darwinism came into its own: an understanding of the physical world need not trump belief in a Creator. “Nothing can be more injudicious or less equitable than to blend or confound these two forms,” he wrote. “It would be equally presumptuous and unreasonable to judge the records of the one [i.e., God] with the fluctuating inferences of the other [i.e., nature]; while on the other hand, to interpret the real or apparent facts of the latter in accommodation to the declaration of the former could only tend by interrupting the progress of Science to prevent it from reaching that higher ground, from which we need not doubt that both will be seen in perfect Harmony” (emphasis added).

How the Bible is understood and applied is subject to human interpretation and a kind of reception history; we read it in light of our own experience, preconceived opinions, and scientific claims rather than allowing it to speak for itself. This was certainly the source of Darwin’s difficulty, which has descended to us today. It is not beyond imagining that straightforward reappraisals of both our science and our religion will be necessary in order to rediscover the harmony that exists between Creator and creation. Our “big brains,” as Kurt Vonnegut concluded, often get us into trouble. We must unravel our thinking in order to discover the true unity of life.