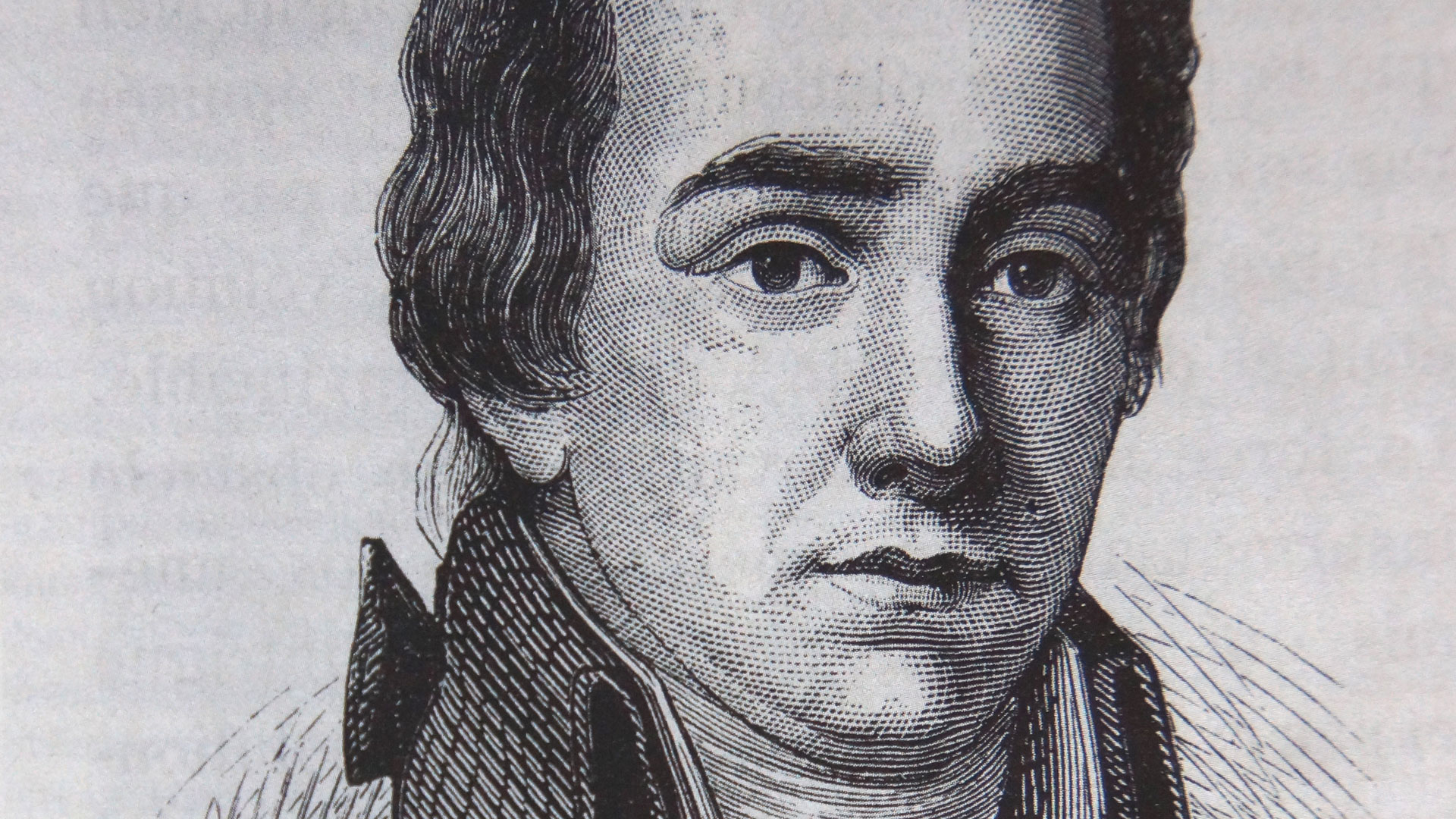

William Wilberforce: The Persevering Parliamentarian

In one of the last letters of his life, 87-year-old John Wesley, founder of Methodism, wrote to a young member of England’s parliament: “Unless God has raised you up for this very thing, you will be worn out by the opposition of men and devils. But if God be for you, who can be against you?” Wesley was referring to William Wilberforce’s hope of abolishing slavery throughout the British Empire. At the time of the letter, Wilberforce had been pursuing the cause in parliament for nearly four years. It would take 16 more years before the slave trade would be outlawed, and the rest of his lifetime before slavery itself was abolished.

Wilberforce was born August 24, 1759, into a prosperous Yorkshire merchant family. His father died before William was nine, securing the boy’s financial independence. At the age of 17 he enrolled at Cambridge University, where he was well liked for his parties and his warm and fun-loving nature. In fact, he preferred socializing and playing cards to attending classes.

With no interest in the family business, Wilberforce decided to pursue a career in politics. He spent the winter of 1779–80 in London, enjoying the social life and observing debates from the gallery of the House of Commons. Another young man also spent his time in the gallery that winter—the future prime minister William Pitt (the Younger). A lifelong friendship began. Both became members of the House of Commons within the year and relied on one another for advice and support throughout their careers.

In 1784 Wilberforce boldly campaigned for the largest constituency in England and won. Although small in stature and weak in constitution, he spoke with a skill, warmth and passion that easily won people over. One parliamentary reporter described his speeches as “so distinct and melodious that the most hostile ear hangs on them delighted,” while Pitt once remarked that Wilberforce had “the greatest natural eloquence of all the men I ever knew.”

The following winter Wilberforce took his mother and his sister on a trip that transformed both his life and his politics. An old acquaintance had joined them, and throughout their journey the two men discussed, among other things, the New Testament in Greek. In the months that followed, Wilberforce reflected on his life and its excesses, and began to regret his idleness, indulgence and lack of political direction. He felt compelled to change but struggled with the decision. Becoming a Christian would place him outside his social circle. Questioning whether he should withdraw from politics, he consulted John Newton, the former slave trader who wrote the hymn “Amazing Grace.” Newton encouraged Wilberforce to continue in politics, believing that God could use him “for the good of the nation.”

Wilberforce quickly made up for lost time—politically and personally. He began his first humanitarian reform while continuing his previous support of parliamentary reform. Adopting a rigorous routine of self-examination, he wrote down his goals and evaluated his motives, words and actions at the end of each day. He lowered his tenants’ rents, wrote lists of those needing prayer, studied his Bible and fasted.

It was during this time that he was asked to bring the topic of the slave trade to parliament. A growing body of people had been working to raise public awareness of its evils, but they realized that for such an important economic trade to end, parliament must outlaw it. Wilberforce carefully reviewed the information they presented and then did his own research. Confronted with the evidence of inhumane treatment and the high death rate on the slaves’ sea passages, he became convicted that slavery was wrong, concluding, “I would never rest till I had effected its abolition.”

“As soon as ever I had arrived thus far in my investigation of the slave trade, I confess to you sir, so enormous, so dreadful, so irremediable did its wickedness appear that . . . I from this time determined that I would never rest till I had effected its abolition.”

It became apparent, however, that there was neither the political nor the popular will to banish slavery outright, so Wilberforce began by campaigning only against the slave trade, feeling this could be more easily achieved (it actually took 19 years!). At the same time, in May 1787, some of those who had been active in the antislavery movement formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Wilberforce collected statistics, evidence of mistreatment, and mortality rates. But when the time came to bring the issue to parliament, he had fallen ill. He turned to Pitt for help, and in May 1788 the latter moved that the House should investigate the slave trade.

The parliamentary debate began in May 1789. Many voiced opposition, fearing that Britain would be economically disadvantaged if the slave trade were outlawed. Others lacked sympathy because of the commonly held belief in the divine placement of one race of people over others. Slave traders painted a rosy picture of the slaves’ circumstances at sea and argued that the high death rates were simply due to epidemics. Wilberforce dealt with each argument presented and went on to propose 12 resolutions. In his first antislavery speech, he appealed to members to think beyond the immediate and to view their responsibility from an eternal perspective:

“There is a principle above everything that is political. And when I reflect on the command that says, ‘Thou shalt do no murder’, believing the authority to be divine, how can I dare set up any reasonings of my own against it? And, Sir, when we think of eternity, and the future consequences of all human conduct, what is there in this life which should make any man contradict the principles of his own conscience, the principles of justice, the laws of religion, and of God?”

The debate was adjourned for nine days and ultimately delayed by a further two years. It was not until April 1792, after Wilberforce’s opponents inserted the word “gradual” into the proposal, that the House voted that the slave trade should eventually be abolished. But without a time line, Wilberforce’s victory had no substance. The slave trade continued in force throughout the 1790s.

In May 1793 Wilberforce proposed the Foreign Slave Bill to prohibit British ships from carrying slaves, but the bill was defeated in the House.

Meanwhile Wilberforce devoted his time to many other social causes, such as the education of the poor, penal reform, and paying the debts of those in debtors’ prisons. But, in his words, “the grand object” of his parliamentary existence remained the abolition of the slave trade.

In March 1796 Wilberforce lost another bill, this time by only four votes, but it soon became apparent that slavery would not have parliament’s attention again until the French Revolution was over. In the intervening time, Wilberforce focused on what he termed “the reformation of manners.” As he considered the root of social problems, he came to the conclusion that if the morals of the country could be reformed, then crime, poverty and other problems would diminish.

“How different, nay, in many respects, how contradictory, would be the two systems of mere morals, of which the one should be formed from the commonly received maxims of the Christian world, and the other from the study of the Holy Scriptures!”

He noticed that the Christianity found in the Bible contrasted sharply with the accepted religious practice of the day. In April 1797 he published A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Higher and Middle Classes in This Country, Contrasted With Real Christianity. The book proved very popular and went on to be published in five languages.

The antislavery movement revived in 1804, and the following year a bill for the abolition of the slave trade to conquered territories was successful. Capitalizing on this new momentum, Wilberforce wrote “A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade, Addressed to the Freeholders of Yorkshire,” and on February 23, 1807, the House overwhelmingly voted in favor. Tears ran down Wilberforce’s face as he listened to the final result and was honored by parliament for his efforts. According to biographer John Pollock, “his achievement brought him a personal moral authority with public and Parliament above any man living.”

Continuing to campaign for penalty clauses to ensure compliance with the new law, Wilberforce saw an amended Abolition Act come into force in March 1807. The slave trade was now officially abolished throughout the British Empire. Still, he did not think the climate was right for total emancipation, believing that slaves must be prepared for freedom.

In 1812 Wilberforce resigned his Yorkshire seat, enabling him to spend more time with his family and to look after his failing health and his many charitable organizations: some estimate that he was president, vice president or committee member of no less than 69 societies.

In 1816 Wilberforce launched a bid for a Registry Bill, which would require colonial legislatures to register all slaves, as it was suspected that some colonies were importing slaves illegally. At the same time, diplomatic negotiations began with Portugal and Spain to abolish their slave trades. Despite all this, little progress on the actual end of the practice of slavery was being made, and the hope that slaves would be treated better following the end of the slave trade was not realized.

Wilberforce began pushing for the liberation of all slaves in 1821, and in 1823 he and others formed the Anti-Slavery Society. He now wrote Appeal to the Religion, Justice and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire in Behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies, addressing the belief that negroes were “degraded” because of their race. He argued that the men of Sierra Leone (a self-governing black community) and Haiti (the first black-ruled country), had shown themselves, in biographer Pollock’s words, to be “true men, not the brute beasts which some planters believed negroes to be.”

In March 1823 he presented parliament with a petition for the abolition of slavery. Ailing health prevented him from engaging in all of the parliamentary debate that ensued, but others took the cause forward. In June 1824 Wilberforce made a short speech asking the House not to rely on colonial governments to end slavery. The debate continued over the next few years, and the antislavery movement garnered increasing parliamentary support in the process.

By February 1825, after many pleas from his physician, Wilberforce retired from government, though he continued to encourage the movement as best he could. In 1831 he sent a message to the Anti-Slavery Society: “Our motto must continue to be perseverance. And ultimately I trust the Almighty will crown our efforts with success.”

On July 26, 1833, the act for abolition of slavery passed its third reading in the House of Commons. Wilberforce died three days later, but by then passage through the House of Lords was certain. He was buried in Westminster Abbey by request of members of both Houses of Parliament. Slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire the following year.